When I asked Ali, “Where did you learn such good English?” his answer amazed me: “At the felons ward at Sepidar Prison in Ahvaz.”

“I decided that I had to survive my time in prison whether I liked it or not,” he told me. “I was worried that my life was being wasted. I noticed that not all the inmates were wasting their time inside prison. Some were thinking about the future. They were studying hard. I thought I could also see the fruits of a productive time in prison when I am released. Could it be that I could know more when I got out of prison then when I went in?”

Sepidar Prison is one of two prisons in Ahvaz, the capital of Khuzestan province in western Iran. Human rights organizations report that guards regularly torture inmates at the prison, and that Arab activists face brutal discrimination. But guards do leave some prisoners alone, like Ali, allowing him time to study.

After three years at Sepidar, Ali has become fluent. He says he received very little guidance and learned English with just the very basic tools at his disposal. “I pleaded with prison officials to get me a dictionary from my family,” he says. “Don’t think for a moment that it was easy, but eventually it arrived. I opened it immediately, and started memorizing English words from the first letter of the alphabet. I did this for a year and a half. I think my efforts were successful. I have a good vocabulary now.”

Almost all prisoners interested in learning English in Iranian prisons do so with the help of cellmates with better English language skills than them.

“At Evin there are close to 200 foreign prisoners, most of whom come from African countries,” says an inmate named Karim. He says his attempts to learn English at the prison — known for detaining a large number of political prisoners — have been largely unsuccessful. Every week, an English teacher holds a class for them to instruct them in religious matters. But there is a lack of a coherent or systematic class schedule for learning languages.”

Karim says he doesn’t know many prisoners who actually want to learn English — or even want to teach it, if they know how to speak English. “Before going to prison I ran a language school. Inside prison, I have spent a lot of energy to help prisoners held on security-related charges to enhance their knowledge of English. But up to now I have not had much positive feedback. Perhaps this is because of psychological pressures, or because people are distracted with other matters. It’s also to do with lack of concentration or motivation.”

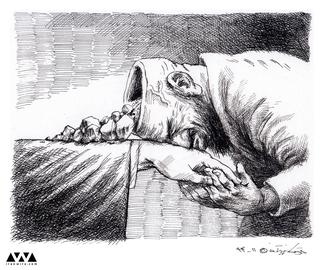

According to a number of inmates at Evin, there is absolutely no chance that prisoners who are serving time for drug trafficking or murder will take up a second language. Why would they? Their chief preoccupation is saving themselves from execution. The same thing is true in the ward for drug addicts. These prisoners are unlikely to want to teach or learn a second language, they say.

In addition to Karim, a few other prisoners at Evin also offer language classes, though according to one prisoner, Younes, the prison does not offer formal facilities for learning. Whatever Younes has learned, he says, is down to the kindness of his former cellmate, who was fluent in English.

“Young prisoners are the most enthusiastic about learning a language in prison. Often they want to immigrate after they have served their time. They are eager not to fall behind in terms of learning and hope that after they are released they will be able to find a proper job, armed with a foreign language. Older inmates are less motivated. They often stop studying, and then start up again. They don’t make much progress. It’s like they’re running in place.”

The Political Prisoners Ward at Evin: The Place to Learn English?

But some say the situation is different in Evin’s Ward 350, the communal ward for political prisoners. Saeed, a prisoner of conscience who has been there for a year, says inmates carefully organize and manage regular language classes. He agrees with Younes and says there is a powerful motivation behind their enthusiasm: the prospect of immigration or seeking asylum after release. But here it is not difficult to find an inmate who is fluent in English and willing to help other prisoners. It is also possible to learn English on Ward 209 at Evin, which is controlled by the Intelligence Ministry. Again, many inmates help their cellmates learn if they are interested.

Political prisoners at Rajai Shahr Prison in Karaj near Tehran also regularly learn English, learning on their own as they do in quite a few wards around the country, including at the newly-built Fashafuyeh prison in southern Tehran.

Given the huge differences in attitudes and approaches toward inmates' acquiring language skills, it is no surprise that established or specific methods for teaching and learning English have not been adopted across Iranian prisons. At Evin, most prisoners use the Interchange methodology, publications produced by Cambridge University Press in the United States, or the Streamline series by Oxford University Press in the United Kingdom. Good quality videos and DVDs with Persian subtitles are available. But books and learning aids, including videos, are expensive, meaning MP3 players are big business in prisons because they allow inmates to share and copy language-learning material.

In most cases, this material is considered contraband and must be smuggled into prisons. Diligent students must use devices for watching or listening to language courses when guards are not looking, and make sure they hide books from sight.

Whatever the obstacles — and risks — involved, it is clear that English language learning is a big pull for some Iranian prisoners, particularly those who have accepted that their future after prison may be outside of the country. Many prisoners believe that using their time wisely while they are locked away gives them some hope, and that learning English will set them up for their new life, wherever that may be.

Read more in the series:

Iran's Political Prisoners: It helps to have a US passport

The Rape Ward at Tehran’s Rajai Shahr Prison

A Baha’i Brought an Al Qaeda Man in from the Cold

Saved from the Gallows: The Passports that get you out of Iranian Jails

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments