During the eight-year Iran-Iraq war, from 1980 to 1988, thousands of Baha'is, like their compatriots, went to the front line and dozens of them were killed, wounded, or captured. The Islamic Republic is reluctant to name them along with other martyrs of the war. In a series of articles, IranWire introduces the Baha'i martyrs of the Iran-Iraq war.

If you know of any Baha'i martyrs and have a first-hand narrative of their lives, contact IranWire.

***

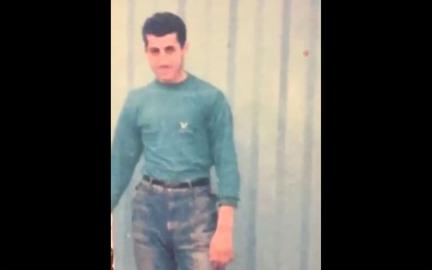

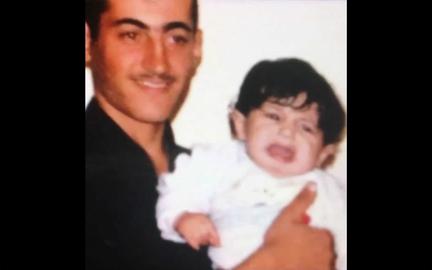

More than thirty years after his brother was killed, she still weeps quietly when she talks about him. She remembers the days when Farhoush, her brother, was eagerly preparing for military service. The family tried to dissuade him from his decision. Before him, his two older brothers had served in the war, and one of them had been injured by an explosion. But Farhoush was determined to go to military service.

He had many plans for his future – but none of them were possible without going to the war. Farhoush was a Baha'i and was not allowed to enter university due to his religious beliefs. It was not possible to return to the village where he was born; there were no young people left in the village, and everyone had moved to the cities to work and study. And after the Islamic Revolution, the Baha'is of the villages of Mazandaran province were pressured to leave their homes. Their houses and paddy fields were set on fire. At night, attackers cut the trees on Baha'i lands. Houses, barns and fields were stoned. Many Baha'i villagers had to leave. His parents had been living in Ghaemshahr for some time.

His religious beliefs themselves also strengthened his determination to join the military. In the Baha'i faith, service to the homeland and obedience to government are considered core beliefs, as far as this does not contradict the beliefs of the Baha'i faith. The government had called all citizens to enlist in the military. Farhoush believed in his patriotic duty as a religious obligation. And yet he also knew that the same government deprived him of many citizenship rights such as the right to education, the right to work and even the right to choose his home.

Birth and adolescence

Farhosh Asadi was born in 1969 in the village of Ziarkola (now part of Simorgh County in Mazandaran) to a rural Baha'i family. The Asadi family, like most rural families in the north of the country, lived on agriculture and animal husbandry. Farhosh was the fifth child. He spent his childhood in the village. Then he went to his brothers and sisters in Shahi (today's Ghaemshahr) to study and started in the sixth grade of Bahman school in Ghaemshahr.

Farhoush had sold street-side handicrafts since he was a teenager during the Nowruz and summer holidays to earn a living. Once every few days, municipal officials raided vendors' shops and confiscated their belongings. Farhoush and other peddlers had to change spots regularly. Sometimes, they spread their wares in Sari, in Babol or in Tehran.

Eventually, Farhoush grew weary of the hassle and loss of capital and spent his last two years working in a sandwich shop. It was not long after his work in the shop that the owner of the shop was threatened by several fanatical locals to expel his Baha'i worker. The owner, who liked Farhoush's trustworthiness and honesty, did not fire him, but Farhoush decided to work in the sandwich shop only two days a week to be less visible.

At that time, young people had two options after graduation: university or military service. For Baha'i youth deprived of university education, there was only one way: to go to the military. Many Baha'i youth went to Pakistan to study, from where they went to study in other countries. But Farhoush preferred to stay at home rather than leave Iran. He decided to live and work with his family, friends and compatriots in his home country after completing his military service; although he was aware that as a Baha'i he would be deprived of many citizenship rights.

In the summer of 1988, the beginning of his military service began near the end of the eight-year Iran-Iraq war. Farhoush passed the military training course in Tehran and at the end of October, after a few days of leave, he returned to the barracks and from there was sent to Sardasht.

At that time, on the orders of military intelligence, soldiers of religious minorities had to report to the Security Office. This was done to identify non-Muslim soldiers and to monitor them until the end of their service. Farhoush also reported himself as a follower of the Baha'i faith.

During training, Farhoush did not face any problems due to his religious beliefs and was treated like other soldiers. But in Sardasht the situation was different. In letters to his sister, he wrote that his commander had been harassing him ever since he realized that he was a Baha'i. Long and uninterrupted rotations on guard duty were part of this treatment.

Farhoush's non-participation in congregational Islamic prayers made the situation more difficult for him. He wrote to his sister that he was given leftover food by the commander and that he ate dry bread and water in the morning. Commanders prevented other soldiers from talking to him. His sister expressed concern, but Farhoush said he was not willing to leave the service, and that one day all these difficulties would end.

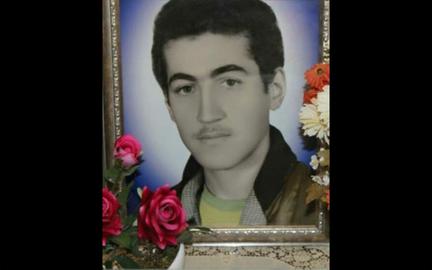

A few days before Farhoush's first leave, several officers went to his sister's house in Ghaemshahr and informed them that Farhoush had been shot the day before and was currently in a hospital in Tabriz. On the same day, Farhoush's father left the village of Ziarkola with his son and son-in-law for Tabriz. At the hospital, they found out that Farhoush had been taken unconscious from Sardasht to a hospital in Tabriz after being shot. On January 9, 1989, after two days in coma, Farhoush Asadi died of a gunshot wound to the head.

After Farhoush's death, the army refused to deliver the body. According to Farhoush's sister, the army representative told Farhoush's parents that Farhoush Asadi was their soldier and that they would bury him themselves. The army refused to allow Asadi's family to bury their son's body according to their religious rites. One or two days later, the Asadi family found an acquaintance in the army and managed to retrieve their son's body and bury him in the Baha'i cemetery in Ziarkola village.

Farhoush's sister says that the army announced the cause of her brother's death as an "accident" and when her parents asked for the real cause, the army replied that the family had to pay for the shooting and that the body would not be delivered for further investigation. As a result, the Asadi family stopped pursuing the killing of their son.

Ms. Asadi said that the army was looking for an excuse to refuse to deliver Farhoush's body and to close the case. If his father wanted to follow the story of her brother's murder, it certainly would not work, because since the victory of the Islamic Revolution, no court in Iran has ruled in favor of a Baha'i, especially if one side of the case is the army. At that time, it was best to take the body of their youngest son and bury him according to Baha’i practices. After this incident, Farhoush's parents were emotionally broken without their children.

According to Ms. Asadi, the funeral was held in the village of his birthplace, Ziarkola. No one represented the army, and no concessions or assistance were given to the Asadi family by the army, despite the fact that the representatives of the army in Tabriz insisted, because Farhoush was killed in the line of duty a soldier, that he was a child of the army and it is the responsibility of the army to bury him.

Farhoush's sister ends her narrative by saying that, despite the burial of her brother in the Baha'i cemetery, her father guarded his grave for one to two months, because they had heard that some villagers wanted to exhume the body and bury it in the Ziarkola Muslim cemetery according to Islamic rituals. They said that because Farhoush lost his life in military service, he is a Muslim and cannot be a Baha’i.

See related articles:

Farhang Shah Bahrami: An Iranian Baha'i Martyr of War

Mehrdad Badkoobeh: An Iranian Baha'i Martyr of War

Saeed Masoudian: An Iranian Baha’i Martyr of War

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments