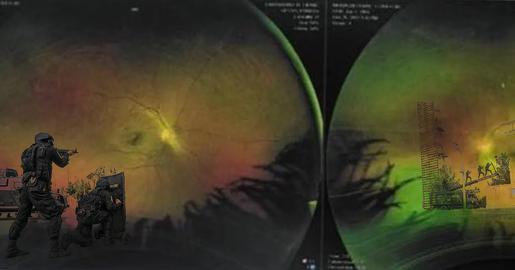

As IranWire has reported, hundreds of Iranians have sustained severe eye injuries after being hit by pellets, tear gas cannisters, paintball bullets or other projectiles used by security forces amid a bloody crackdown on mainly peaceful demonstrations. Doctors say that, as of now, at least 580 protesters have lost one or both eyes in Tehran and in Kurdistan alone. But the actual numbers across the country are much higher.

The report concluded that such actions by the security forces could constitute a “crime against humanity,” as defined by Article 7 of the Rome Statute.

In this series of reports, IranWire presents the victims’ stories told in their own words. Some have posted their stories, along with their names and pictures, on social media. Others, whose real names shall not be disclosed to protect their safety, have told their stories to IranWire. IranWire can make their identities and medical situations available to international legal authorities.

***

September arrives, carrying with it poignant memories of the year since the death in custody of Mahsa Amini. Her untimely demise became the catalyst for a series of events that set Iran ablaze with protests.

The unrest, which lasted months, resulted in the detention or imprisonment of more than 20,000 people, hundreds of deaths during the violent government crackdown, executions and the agonizing irreversibility of countless individuals losing one or both of their eyes. And for these protesters, whose eyes had been targeted by security agents, each morning marks a fresh confrontation with a life of impaired vision.

A year has passed since those fateful days, and yet the shadow of their lost eyes persists, for some even blurring the line between day and night. The Islamic Republic has cast a shroud over their world – challenging their resilience and fortitude.

Activists, protesters, political prisoners and victims stand at a crossroads, where the unyielding pressure exerted by security forces has forced many Iranians to choose between staying or leaving their homeland.

Among them is Milad Safari, a father of two, who lost his sight after being wounded during the upheaval. Safari chose to leave Iran for the city of Mainz in Germany – where he hoped to find a brighter future.

We have just arrived in Mainz and are preparing to film our interview with Safari. In the courtyard of the Maltzer non-profit foundation, overseen by Behrooz Asadi, a political and civil activist, we meet him. While we are adjusting lights and setting up the shot, he enters and collapses on to a sofa, engrossed in his phone.

He is mourning a close friend whom he lost just hours earlier. But he also smiles, though it is perhaps a bitter smile, when his family calls.

I approach Safari as he cradles his head in his hands and sit beside him. A shared smile bridges the gap between us, and I peer into his eyes, uncertain of how much he can perceive with the wounded one.

"Why not shield your eyes to prevent further harm?" I ask.

Safari says, "Since the beginning, my children disliked seeing me wear blindfolds. I don’t use them. Instead, I wear a pair of sunglasses whenever there’s too much light and wind."

A father of two, Safari has been following their well-being day and night through the virtual window of his phone.

Yet, during his time in Iran, Safari admits to being more of a father in image than in reality. He says he managed to spend a mere day and a half with his children each week.

His routine involved commuting between Kermanshah and Tehran, a distance of more than 500 km, arriving in Kermanshah on Wednesday nights and departing for Tehran on Friday evenings.

Similar to numerous Iranian Kurds, Safari’s employment prospects in his hometown were limited. He and his family were therefore left with only one and a half days together each week. The remainder of his time was spent as a laborer in an unfamiliar city.

It was close to this city, Tehran, that he found himself amid the protests. A laser targeted his face during the protest and the result was the loss of one of his eyes.

It was September 22 – the sixth night of the protests. On his nights in Tehran, Safari went to his sister’s home in Mehrshahr, Karaj, near the capital, to spend the night.

But that night was different. He joined the protests accompanied by a friend. The Chahar-Bandeh area of Tehran, characterized by its four lanes, central boulevard, and a tree, was thronged with people. Safari, not one to remain passive, urged people near him not to relent.

Tear gas was fired by the police at the demonstrators. Disguised motorcyclists emerged from the rear to suppress the crowd.

Safari moved toward the sidewalk, seeking shelter, when a green laser pointed at his face. He had been singled out. He shielded his eyes from the laser as the sound of pellet shots rang out. The echoes of pellets striking the closed shutters of the shop behind Milad still linger in his memory.

Two pellets pierced his eye. One was later removed – leaving five still embedded in his body. A pellet remains lodged in his fingertip and Safari extends his hand to the camera, inviting me, "Feel it."

My fingers touch the metal fragments within the flesh of his finger. I go back behind the camera.

"I take pride in it. I took to the streets for my convictions, and regardless of the consequences, it no longer matters,” Safari says.

In the nights before the one that robbed him of his sight, Safari had written a will. Speaking on Instagram with a friend, he had said, "I'll be on the streets tomorrow. If I don't return, please take care of my family.”

But he had never imagined that the riot squad's intention was to blind him.

Safari underwent three surgeries on his eye. He removes his glasses, revealing the stitches. And as he tells his story, there’s a simmering undercurrent of frustration and impatience, particularly when he mentions his mother.

Safari held back the truth about his injured eye from his family until after the second surgery. Conflicting reports had reached his father and the two arranged to meet at a park near their home. When he saw his son’s bandaged head and eyes, the father's legs gave way, and he collapsed on to a park bench. Father and son embraced, tears mingling in their shared sorrow, their grief intertwining as they held each other.

And he had yet to break the news to his mother.

Safari remembers this episode with a mixture of anger and emotion. "My mother is an incredibly caring person,” he says. When she saw her son, her strength faltered, and she fainted and crumpled to the ground.

Safari also dwells on his children – remembering that he once purchased a toy gun for one of them. While playing, the young boy, wielding his plastic gun, approached his father and said, "Daddy, cover your eye so I can shoot."

Safari says, "It's striking that even a four-year-old understands the significance of protecting one's eyes from harm, while those who caused this damage failed to grasp it."

When he left Iran, Safari had to cross borders and travel across countries illegally, until he reached Germany. Speaking with his children became a source of strength and propelled him on.

"The Iranian people have reached an impasse,” Safari tells me. “Place yourself in Mahsa's family's shoes. You'd have taken to the streets. What if this had happened to my own sister?"

He says, "Hatred defines the Islamic Republic for me."

Safari’s life as a Kurdish Iranian, a migrant laborer within his own country, earns too little to afford a decent life for his wife and children or even a modest home where they can live together. And seeing his children beyond just photographs will elude him for years.

The interview ends with Safari reflecting on the rights women enjoy in Germany. Why does the Islamic Republic subject women in Iran to such violence?

We switch the camera off and part ways. Safari rises and heads to the courtyard. We discuss the future. He needs to learn German and find a job so that he can bring his family – to embrace his children as a father. The Islamic Republic injures not only those in its prisons, or on the streets of Iran, but even people far away in small towns around the world.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments