In May this year Fars News Agency, one of the IRGC’s public mouthpieces, published a furious response to a broadcast by Voice of America’s (VoA) Persian service (regarded by Tehran as one of Washington’s public mouthpieces). The broadcast had apparently suggested that had it not been for the Islamic Revolution, “Iran would now be the first power in the region.”

The Fars reporter held that yesterday’s weakness was today’s strength, praising Iran’s supposed modern military might. But its main refutation of the “laughable” VoA article was: “This is the same army which did not resist the Allies for more than three days.” The piece taunted other perceived Pahlavi-era shortcomings, such as the loss of Bahrain and the reliance on American military advisors, but it was the reference to the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran during World War II that stood out.

The fact that Britain invaded Iran, ostensibly exemplifying the behemothian behaviour of the imperialist bully Britain as depicted as in the popular narrative of Iranian history, is one thing. And it must delight the IRGC to have an example of this to hand. That the Iranians mostly surrendered in quick order is quite another. Anglo-Indian forces lost a mere 20 killed and 50 wounded; the campaign was over in three days, the war in four. It was, as the military historian Robert Lyman writes, “one of the fastest capitulations in history”.

The invasion of 1941 is presented by the Islamic Republic today as an abject military failure. The fact that it took place during Reza Shah’s reign also makes it easily passed off as an example of the despotism, cruelties and inherent weaknesses of the then-state, and an instance of “perfidious Albion” in action.

In reality, it wasn’t as simple as all that. There was a good deal more to this period than a “three-day defeat”. A proper historical reckoning with the events of 1941 reveals that this was a fascinating period in Iran’s history; rather than being reduced to a black-and-white tale of imperialist onslaught and craven capitulation, the events of that period help us understand some important aspects of Iranian foreign policy today.

The Abdication in Tehran

World War II in Iran was bookended by unsettling political sea changes: the Constitutional Revolution in 1905, the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the end of over a century of Qajar rule in 1921. Then in 1941, the Anglo-Soviet invasion gave rise to another seismic change in the form of Reza Shah’s abdication. The seamlessness and lack of fanfare merely disguised its effects.

A change of Shah was not unusual by itself. Reza Shah’s predecessor, Ahmed Shah Qajar, had been swept aside in a remarkably non-violent coup by the then-Reza Khan. And his father, Mohammed Ali Shah, had abdicated during the Constitutional Revolution, but only after various, forceful and failed attempts to re-establish himself. To see a monarch abdicate peaceably, and for that monarch to have been as effective a despot as Reza Shah, was a first.

Iranians’ reactions were mixed, but almost all detected a seismic change to business as usual. General Hassan Arfa, commander-in-chief of the defence of Tehran, was greatly moved: “I felt as if the ground on which I stood had been taken from under me.”

Arfa’s chauffeur reacted differently. The General was shocked one day shortly after the abdication when the latter drove him up a one-way street the wrong way. He bellowed for an explanation from the back, and the driver explained that it didn’t matter anymore, because Reza Shah had gone. The arbiter of the modern, military, law-abiding state had vanished.

In his father’s place a 21-year-old was rushed to the throne. Mohammed Reza Shah, who had until then been shut up in a Swiss boarding school, or else cocooned at court, was not prepared for rule. On hearing the news of his accession, and of his father’s leaving for South Africa, Mohammed Reza apparently started weeping and begged his father to take him with him.

It is hard to blame him. Ann Lambton, a then-British press attaché who shocked Persian conservatives by bicycling around Tehran to garner the public’s opinion of the Shah, wrote in 1940 that people thought “the Crown Prince, in the event of the Shah’s death, may not succeed in establishing himself [as King].”

He just about managed. But this unpreparedness at the time of his accession, and his regnal immaturity once on the Peacock Throne, were apparent throughout his reign. Thirty-seven years after the 1941 invasion, the long consequences for Iran’s leadership would pave the way for the emergence of what became the Islamic Republic.

An Entrenched Fear of Russian Attack

As Fars News Agency’s article shows, there is a lingering bitter taste for some over the Allied invasion and occupation of the country. This is partly because the invasion was as much a reflection of Britain and Russia’s peacetime, and traditional, policies towards Iran as it was of the necessities and realpolitik of the war.

When Indian and British troops from the 24th Indian Brigade spearheaded Operation Countenance at 4.10am on August 25, 1941, over a pontoon constructed by dhows lashed together across the Shatt-al-Arab, they did so for several main strategic reasons. The first and most important of these was the USSR.

Originally the British operation was not conceived as a means of countering a German offensive, as it eventually became. It began as a defensive measure against Soviet expansion into Iran. It wasn’t a mere example of pure, self-serving British policy either; Iran and Iranians were also dogged by a fear of a Soviet invasion.

Russian aggression had beset Iran consistently throughout the 19th and 20th centuries and going back to at least the Napoleonic Wars. The tumult of the Russian Revolution had drawn the Russian military away from Iran during World War I, but now, recovered from internal turmoil, they were again sabre-rattling at the border.

As Robert Lyman outlines, the USSR had long had a “threefold strategic aspiration” in Iran: eradicating British influence over Tehran, severing British ties with Middle Eastern oil (and with India), and securing a warm-water Russian port, all of which “could be brought about through an invasion of Iran”. The expansion of Russian territory and the Soviet foothold in Iran were additional motives. The Azerbaijan Crisis of 1946 later ratified this concern.

Soviet troops’ presence in the Caucasus had increased by more than 50 percent since the start of the war. In 1939 there had been 40 Soviet aircraft on the border with Iran; this had increased tenfold within a year. Worse, Hitler was also encouraging the USSR to “involve itself” in the Middle East. In then-anticipation of the downfall of the British Empire, Hitler offered to cede Iran to Soviet Russia in the carve-up of the spoils. Stalin had enthusiastically agreed.

Meanwhile, Britain had pledged Iran (while encouraging her neutrality) to go to war in the event of Soviet invasion. Indeed, one of the reasons Britain had not declared war on Russia in September 1939 was because of the fragility of the situation in Persia and a fear that Russia “might use it as a pretext for invading Iran”.

This website has written previously about Iranians’ nascent fear of Russian aggression in the present day, and how it was reignited after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February this year. So it was then. The famous Australian war correspondent Alan Moorehead wrote that while he was in Iran in the early part of the war, people had been terrified of the Russians; rumours abounded of rape, pillage and murder.

And according to General Arfa, in the early part of the war fear gripped the population “lest Iran become the next victim… everybody was expecting a Soviet drive into Iran with German approval”. This same fear, he said, blighted Iranian officers too, and one of the reasons reason soldiers abandoned their posts so quickly during the inasion was they “did not see any sense in remaining to be slaughtered [by the Soviets] like the hapless officers of the Polish… armies”.

Anglo-Iranian Relations: A Complicated Reality

Far from being a simple narrative of conquer-defeat, and far less acknowledged by the Islamic Republic today, is the 1941 was also a typical example of Anglo-Iranian relations enduring – at least behind closed doors. An illuminating point is that during the invasion, Iran’s diplomatic relations were never severed, either with the USSR or the UK. Before the invasion, Iran made secret overtures to Britain for more arms, particularly aircraft, for defence against Russia.

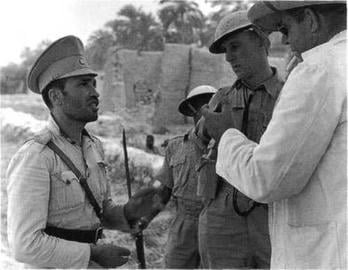

There is one story in particular which seems to signify the tragic irony of the British invasion. While the majority of the Shah’s armed forces did lay down their arms in quick order, the Persian defence was, in fact, not without courage.

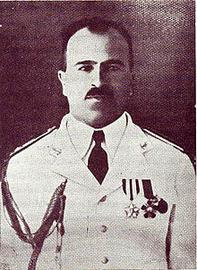

The Iranian Navy continued to resist the Allies even after ground troops had given up the fight, and after one man, Admiral Gholamali Bayandor, had rushed from his bed to Khorramshahr to rally what sloops, gunboats and vessels he could against the onslaught from the world’s largest and strongest navy.

After a running fight along the river, most Iranian ships were sunk and Axis merchantmen scuttled. The British had hoped to secure a peace negotiation via Bayandor, who was described as a “profoundly pro-British” close friend of the Shah, and British Intelligence officers had prepared documents to this effect in the hope of securing his signature. This, too, underscores the notion that if there is such a thing, this was an invasion without malice.

It was not what Bayandor had in mind. He rushed ashore and personally manned a machine gun at the radio station, leading the defense of Khorramshahr against the attacking Anglo-Indian troops. He was killed there before anyone realised the identity of an officer one war correspondent later described as a “brave little man”.

Clifford, too, singled out the death in a dispatch to British newspapers; Bayandor was “the hero of the strange, tragic episode.” A British civil servant would later write: “His death was much regretted on our side as well as his own, for he was known to be well-disposed to the Western Allies, though completely loyal to his own King.” And the commander of the Royal Navy in the Persian Gulf wrote of his fallen foe: “His death was regretted by all who knew him. He was intelligent, able, and faithful to Persia.”

Bayandor was buried the next day with full military honors. It gets sadder and more ironic from here: Bayandor’s wife was British. She had been a governess in Syria when they met.

Even today, a class of frigate bears the name IRIS Bayandor in his honour, further emphasising the singularly complex nature of the British invasion of Iran. In the Islamic Republic today, he would have been described as a “martyr”. This was something the author of the Fars article would not have been able – or allowed – to get across.

It is understandable to portray the events of 1941 as a story of straightforward, humiliating defeat by a since-sworn enemy. But it misses the point. The year 1941 was fraught with massive significance for Iran for other reasons. A selective reading like the one promoted by Fars actually speaks to the larger internal conflict within Iranian history – critically, about the public versus private realities of Tehran’s relationships with the West and Russia.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has refocused this contradiction, and the societal amnesia the Islamic Republic has worked hard to promote. In public the Supreme Leader and institutions under his control have rallied behind the Kremlin in blaming “the West”; in private, many officials and ordinary Iranians do not sympathize with Putin.

As Ali Ansari writes, Putin supplies the Iranian regime with its own “ideological talking points…: a healthy dose of Anglophobia… [and] the toxic consequences of Western culture.” But this ideological summit has a historical dead ground, and this is where the events of 1941 lie.

As Alan Moorehead wrote in the bathetic aftermath of the invasion, “the actual fighting, the actual event which changed [this] country’s history, was really a very small thing”. As Fars News Agency’s journalist would have us remember, the invasion lasted only three days. It did not occur in a vacuum. And whether the regime wants to admit it or not, the causes and long effects of the invasion have done far more to shape political realities in Iran today than any propaganda before or since. For understanding Iran today, as much as for history’s sake, it is important that we cut through the mound of simplistic interpretations and grasp the complexities of the Allied invasion.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments