Over the last few months, there have been widespread efforts by the Iranian government to preempt and disarm the anticipated protests coinciding with the 1-year anniversary of the brutal murder of Mahsa Jina Amini for “bad hijab.” International newspapers run stories about authorities arresting journalists, activists, and artists, while police in riot gear roam the streets and the graves of martyrs.

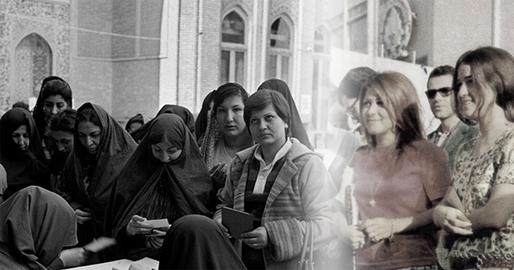

But forced hijab is nothing new. After he returned from exile, Ayatollah Khomeini and his circle wasted no time creating the conditions that would ultimately force women into hijab. Reading the tea leaves, in March 1979, women marched the streets calling for freedom of dress. But to no avail. The new Islamic regime gradually and stealthily forced women to cover their hair and adhere to Islamic laws in their clothing, first in the government buildings, and later in all public areas. Mandatory veiling became one of the most prominent and visible anti-women's rights policies that the new theocratic governing regime enforced.

That is why last year's unprecedented protests led by women and featuring their removal of headscarves was so monumental for the opposition and dangerous for the ruling establishment.

The Media-Power Nexus

As I argue in my book, Media and Power in Modern Iran, a critical component in the regime’s strategy to project and protect its power is dependent on its ability to demonstrate mass public consent to its rule. On holidays and times of political crisis, government backed media outlets run footage of pro-government demonstrations. The evident belief is that such depictions, broadcast all over the country, will serve as evidence that people not only consent to the system of rule but embrace it.

The 2022 protests spoke truth to that lie. Women walking on the streets without their hijab and posting videos of themselves on Instagram was, according to this calculation, the ultimate show of non-compliance. Such symbolic, individual acts joined the rapidly spreading street demonstrations in what became the largest show of public dissent since the 1979 revolution.

Security forces quickly deployed in a massive campaign to identify, imprison, and publicly and privately punish the women and men who took to the internet and walked the streets demanding liberty and a better life. Those who were the most effective and visible online were the highest value targets. Musicians, journalists, Vloggers, and social media stars, were apprehended by the Sepah by the thousands and forced to “confess” to such violations as propaganda against the state and spying for foreign enemies. Others were charged with the highest of offenses and executed, one person publicly.

They also persecuted regular people who dared to protest. Numerous reports attest to IRGC’s blanket strategy of seemingly indiscriminate suppression and punishment; interrogating, torturing, and evening subjecting people to sexual abuse, including genital mutilation and rape. There seemed no limit to their atrocities.

Technologies of Oppression

The regime’s technological capabilities for surveillance and repression shown in 2022 continue to grow. Authorities recently announced it will be deploying AI driven facial recognition software for identifying protestors and those violating Hijab. The quality of such software is yet to be seen. Regardless, the announcement will likely have, by design, a deterrent effect, making those considering such acts of public defiance think again.

The danger of such technology is not limited to those Iranians bold enough to remove their hijabs in public. It is a danger to anyone recorded on a surveillance camera, even those who are not involved in the protests, effectively expanding the possibilities for Sepah operatives looking for an excuse to apprehend or harass virtually anyone who falls in their crosshairs. AI enabled facial recognition is just one example of the state’s cornucopia of media-technologic repression mechanisms.

Perhaps the most important tool is its most far-reaching: the National Information Network, NIN, also known as Shoma.

The National Internet

The idea for a domestic internet, or what is more accurately called “intranet” goes back to at least 2009 in the wake of large, public protests of the election fraud that gave President Mahmood Ahmadinejad a second term. Called the “Green Movement,” or in Western circles, the “Twitter Revolution,” the internet powered demonstrations lasted over a week and were, at the time, the largest showing of citizen discontent in 30 years. For the regime, the experience revealed the danger of the internet as a technology used by protesters to organize and recruit.

When, after days of Green Movement protests, Khamenei ordered the security forces to the street in a violent crackdown, that same technology allowed anyone with a cell phone and internet connection to send images and reports of the state violence, putting the gory details on the front page of newspapers the world over.

The state, for its part, rapidly mobilized to repress the Green Movement, and contain political activity and news of events from circulating at home and abroad. It deployed a bevy of internet countermeasures, including taking down websites and filtering and blocking traffic on social media.

The result was both a win and a loss for the security services, technologists, and politicians behind the effort. Tactically, it was a win in that it successfully silenced the protests and shattered the movement through the aforementioned technical action coupled with arrests, televised forced confessions, and brute force. It was a loss in that the state failed to anticipate the depth of the backlash to the fraud and the precedent the Green Movement would set for protest movements to come.

The most important lesson however was this: in this new, internet connected world, the state’s usual methods of repression, surveillance, and censorship needed a serious upgrade. And so, the idea of an internet fully under the control of the state was born.

The second Ahmadinejad presidency gave way to the less radical administration of Hassan Rouhani, who, along with his Minister of ICT (as well as others) labored to make the dream of a closed internet a reality. The state put into place a number of components critical to a functioning national network following the Chinese and Russian model. It significantly boosted internet speed domestically while reducing the speed of international traffic; improved and expanded telecommunication infrastructure across the country. It attempted to jettison the creation of new state approved content and migrate users of foreign hosted email and communications apps like Telegram to the domestically made (and regime controlled) apps on the national network.

NIN: Forged in the Fires of Widespread Discontent

The last years of the Rouhani administration featured a rising tide of civil unrest. It was then, in the crucible of internet powered protests of 2018-19, that NIN was tested and honed. In the winter of 2018, protests broke out in Mashhad and rapidly spread across the country, with demonstrators decrying the Rouhani administration for the high price of basic foods (and other grievances).

Protests broke out again in 2019 after the price of gas rose astronomically overnight. As I argue in my book, the events of 2018 and 2019 tested the effectiveness of the network, proving the ability of the state to selectively block certain traffic and even “turn off” the entire intranet-- which it did in 2019 for nearly a week.

If the experience of 2018 was proof of concept, and 2019 was a test run for the network, the “Women, Life, Freedom” protests of 2022 showed what Shoma was made for. Soon after the protests erupted on September 16, authorities began blocking WhatsApp and Instagram and imposed a digital curfew, where the internet was largely inaccessible beginning at 4pm and lasting through the night. It blocked the chat functions on video games, access to the Google Play App Store, and, in a tactic from the 2009 playbook, blocked text messages using keywords like Mahsa Amini. Within days, all of the major lines of communication were blocked.

As had been envisioned by its creators, the regime, through these measures and the architecture of the intranet, proved able to cut people's connection to the outside world, while leaving the domestic internet largely functioning. It allowed government offices to continue work as usual and business to continue to communicate with patrons and suppliers (though not on their preferred platforms). All was not perfect of course. Such tactics incurred and continue to incur economic costs.

Looking Ahead

While authorities talk about the benefits of increased security and faster speed, the primary purpose of the National Information Network is control. It allows the members of the ruling establishment control the circulation of videos and photos of what is now becoming a pattern of nearly yearly displays of public discontent with the clerical regime and the rule of the Supreme Leader. Such visual attestations show would-be dissenters that their personal discontent is not limited to them, or one pocket of the country, or even one class. Instead, such images and reportage serve as proof that one group’s grievances are shared by other groups in other parts of the country and that they are not alone in their opposition to the regime.

One can debate whether and how the 2022 protest movement failed. What cannot be debated is that, despite the NIN and brutal violence, it succeeded in further eroding the domestic image of the Islamic Republic as all powerful with popular support.

And while many in the West dream of the day that such protests turn into an armed, national uprising and regime change, the best we can do at the moment is to help those inside and without further undercut the media component of regime power.

By breaking the barriers of the national internet, preventing advances like AI, and finding avenues and technology to expose regime vulnerability and help enable domestic resistance, we can support the cause so many young Iranians have given their life for: freedom.

Dr. Emily Blout is a Georgetown University faculty member at the Center for Jewish Civilization.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments