He has been free for 26 days, but memories of the prisoners he met during his detention continue to trouble him.

“Some of them have nobody, and nobody hears about them,” he says. “They have been charged with baseless political crimes and given long prison sentences that the appeals court has upheld.”

Reza Khandan, the husband of imprisoned human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, was released on bail on December 23. He had been arrested at his home on the morning of September 4, 2018, by intelligence agents who searched his house and found badges declaring “I am against forced hijab”.

He has been tried on charges of “gathering and conspiring against national security”, “propaganda against the regime” and “promoting opposition to hijab”, but the judge has yet to issue his verdict.

Unknown Political Prisoners

Khandan is less concerned about the judge’s verdict than about his former cellmates: ordinary people who have been serving long sentences on political charges.

One he clearly remembers is Ali Baz-Azordeh, who was first arrested in 2006 during protests against a cartoon in Iran newspaper that many in the Azeri community found offensive and insulting.

“He is 27 years old and was arrested during protests against the cartoon when he was 14 or 15,” says Khandan. “He was kept in the Juvenile Rehabilitation Center for two years before he was released.

“He had just turned 18 when he was arrested again as he was putting up a poster during the Green Movement protests [in the aftermath of the disputed 2009 presidential election]. He was taken to the Intelligence Bureau in Tabriz [the capital of East Azerbaijan province].”

Baz-Azordeh told Khandan what they had done to him at the Intelligence Bureau. “This young man described everything in detail,” he says. “He knew the names of all the torture methods and devices, and showed the marks they had left on his body.

“For instance, he said: ‘He hit my forehead so hard that it ruptured.’ Then, with his hands, he showed me the mark the injury had left on his forehead.”

Khandan adds: “Ali was sentenced to five years in prison. He served four years in Tabriz’s prison and the fifth year in exile in Mashhad’s Vakilabad prison. He was 23 when he was released.”

But the story of Ali Baz-Azordeh does not end there. A year ago he was at a gathering with three of his friends and the wife of one of them when they were all arrested.

“They were active on a Telegram channel and posted things against the regime,” he says. “Based on what they had written on Telegram, and even their private chats, the lower court in Nasim Shahr in Karaj sentenced the three men to 18 years and the friend’s wife to eight years.

“You don’t see their names anywhere, although their charges are political. They are enduring their heavy sentences in silence.”

Concealing the Numbers

Before going to prison, Khandan never imagined he would meet so many unknown political prisoners.

“We were all under the impression that since 2009 the number of political prisoners has gradually reduced, or that they have served their sentences and been released. But in prison I was surprised.

“To conceal their numbers, they have scattered political prisoners in various non-political wards. As a result, we have no clear idea how many political prisoners there are.”

Khandan believes that in Evin Prison’s Ward 4 alone there are around 70 inmates charged with political crimes. This is where most prisoners awaiting their final verdict are kept.

“From this number, perhaps only 10 to 15 cases are known and have been reported by the media,” he says.

According to Khandan, some prisoners have no way of informing the media about their situation, while others prefer the press to stay silent.

“They think the judge might use it against them,” he says. “There was one man who had been jailed for five years for espionage, and he hoped to be released after serving a third of his sentence. But he was afraid that if the press wrote about him then this might not happen.”

While in prison, Khandan also noticed that many people had been charged with espionage and cooperation with hostile governments. Based on these charges, they received heavy sentences from the Revolutionary Courts.

“These charges are usually brought against dual nationals and people who have international dealings in business or research,” he says.

“Mohammad Ali Babapour, a young man of 32, is one of those who was charged with espionage. He has a Ph.D. in humanities and was conducting a research project with the approval of the Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies.

“However, he was arrested because he was communicating with a foreign institute in connection with his research.”

In prison, Khandan also met some well-known detainees who have been charged with espionage and working with hostile governments. One of them was Dr. Ahmad Reza Jalali, an Iranian citizen with permanent residency in Sweden who specializes in medicine for disaster relief.

Reza Jalali was arrested on April 24, 2016, just three days before he was to return home after visiting Iran at the invitation of Tehran University. In October 2017, he was sentenced to death on the charge of spying for the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad.

Prosecutors claimed he provided the information that led to the assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists Masoud Ali-Mohammadi and Majid Shahriari.

“I talked with Dr. Jalali for hours,” says Khandan. “His death sentence has been upheld and his physical condition is extremely bad. He did not look anything like his pictures. His bones are showing and he is under enormous psychological pressure.

“When a death sentence is hanging over you, it feels like you are being executed every day.”

“I Am a Hostage”

Khandan also had many talks with Siamak Namazi. The Iranian-American businessman, along with his father Baquer Namazi, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for “cooperating with the hostile government of America”.

“Once, Siamak and I were sitting in the guards’ office because we wanted to go to the clinic. The officer was new and did not know us. ‘What is your charge?’ he asked. ‘Political,’ I said. ‘Security!’ he said. ‘No,’ I answered. ‘Political.’ This was an argument we always had with prison guards and officials.

“The officer then looked at Siamak and asked, ‘Your charge?’ And Siamak said, ‘I am a hostage.’”

Khandan believes that dual nationals who have been convicted on charges of espionage and cooperation with hostile governments are indeed hostages.

“After talking to them, I learned that they are all educated and they love Iran. They have not traveled here for espionage, but only because they cannot cut their emotional ties to the country.

“I have no doubt that Nazanin Zaghari is also a hostage.” Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe is a British-Iranian media charity worker who was sentenced to five years in prison for activities against national security.

Khandan is still waiting for the verdict in his own case.

“When I was arrested at my home, I was immediately transferred to Evin’s Court,” he says. “After a few minutes of questions and answers, I said that I wanted my lawyer, and Mr. [Mohammad] Moghimi got to the courthouse at once.

“They informed me of three serious charges against me, but I am still waiting for the verdict.”

Khandan was released after long hunger strikes by his wife, Nasrin Sotoudeh, and Dr. Farhad Meysami, the civil rights activist who has been in prison since July 31, 2018, for participating in protests against the mandatory hijab.

“Our Children Need Us”

“Before I went to the final session of the court, I wrote a letter to the prison warden and the assistant prosecutor in charge of political prisoners,” says Khandan.

“I told them I would refuse to appear at the trial unless they released either me or my wife to take care of our children, because there was no other way to manage their affairs and their safety. Otherwise I would also go on hunger strike in the coming days.

“But two days before the trial, the assistant prosecutor summoned me and told me to request release on bail. They guaranteed that I would be released on bail. That is why I attended the trial, because I do not recognize the jurisdiction of this court.

“At the trial, Mr. Moghimi argued that my case was political, and therefore the Revolutionary Court had no jurisdiction.”

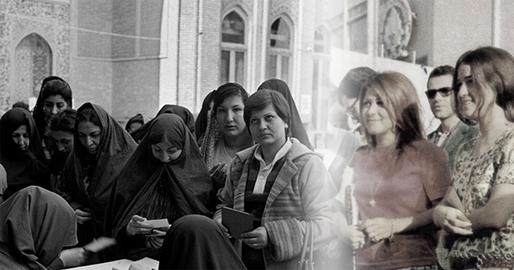

Khandan’s wife, Nasrin Sotoudeh, was arrested at her home on June 13, 2018, after she took up the defense of the “Revolution Women”: women who tied their headscarves to sticks and waved them in public to protest against forced hijab.

At first it was announced that she had been arrested following a complaint by the judge handling the case of Shaparak Shajarizadeh in the city of Kashan. Shajarizadeh was jailed for 20 years in July 2018 for joining the Revolution Women’s protests.

Later, however, the authorities said that Sotoudeh had been arrested to start serving a five-year prison sentence for a 2016 case when she was tried in absentia.

Related Coverage:

“Opposing Compulsory Hijab Is Not a Crime”, December 23, 2018

Civil Rights Activist Refuses to End His Long Hunger Strike, November 20, 2018

Letter from Prison: Why My Hunger Strike Must Continue, October 2, 2018

Women’s Rights Activists behind Bars, October 1, 2018

Jailed Activist's Mother Fears for his Life, September 20, 2018

Friends Fear for Activist 50 Days after he Started Hunger Strike, September 18, 2018

Husband of Prominent Lawyer Arrested, September 5, 2018

The Saga of an Iranian Peaceful Activist, August 30, 2018

Human Rights Lawyer Charged With Assisting Spies, August 16, 2018

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments