In September, President Hassan Rouhani will again visit the United Nations General Assembly in New York, an occasion when world leaders will consider how Iran has changed under his stewardship. It is now over a year since Iranians elected Rouhani to occupy the second most senior position within the power hierarchy of the Islamic Republic. During his presidential campaign Rouhani promised a government of “prudence, moderation, and hope,” promising the nation that he would mend Iran’s relations with the world, end economic sanctions, improve the collapsing economy, secure the release of over 800 political prisoners, and open up the repressive political atmosphere that had been imposed on Iran by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s eight year presidency. After a year in office, how well has Rouhani delivered?

To evaluate Rouhani’s performance we must take into account two important facts: firstly, Iran’s president is given limited power by the constitution; while the president runs the country on a daily basis, he cannot pick his own cabinet (ministers of interior, defense, foreign affairs, intelligence, and culture must be selected in consultation with the Supreme Leader), and is up against hardine control of the judiciary, armed forces and the police. Secondly, the economy that Rouhani inherited from Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was on verge of collapse. Economic sanctions coupled with vast corruption, the incompetence of Ahmadinejad’s economic team, and an inflation rate approaching 50 percent had caused the economy to shrink by nearly six percent in 2012 and early 2013, an economic catastrophe by any measure.

Important Progress

Diplomatically, Rouhani has been a clear success. During his first visit to the United Nations General Assembly in 2013, Rouhani broke two of the greatest taboos that have hung over Iranian politics since 1979: he spoke by phone with President Barack Obama, and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif met with Secretary of State John Kerry. Today, a meeting between senior Iranian and American diplomats is no longer news but routine.

This was followed by the Geneva Accord in November between Iran and P5+1 – the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany – that provided some minor but symbolically important economic relief for Iran. Negotiations between the two sides are continuing and have been extended for four months. The two sides will meet in New York in September and while important differences remain, considerable progress has also been made.

Rouhani’s economic team has also performed impressively, reducing the inflation rate by a significant measure and stabilizing the exchange rate between Iran’s rial and major foreign currencies; the economy is predicted to expand by about 1.7 percent during 2014. The International Monetary Fund reported that the Rouhani administration has stabilized the economy.

The government has also revealed to some extent the scope of the vast economic corruption under the Ahmadinejad administration, ranging from tens of billions of dollars in bank loans to figures close to the hardliners that have not been paid back, to the selling of 25 million barrels of oil by a tycoon, Babak Zanjani, who still has not paid back the $3 billion proceeds, and the granting 3,000 fellowships and scholarships to wholly unqualified children and relatives of hardliners. The last revelation has angered the Majles hardliners, who last week impeached Reza Faraji Dana, Minister of Science, Research and Technology, for his robust action to block scholarship patronage.

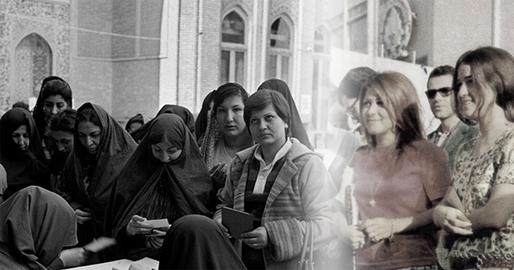

On the cultural front, Rouhani has confronted Khamenei at every turn, responding to virtually each of the Supreme Leader’s proclamations. For example in a speech on April 19, Khamenei rejected the notion that Iranian women should emulate their Western counterparts, claiming that in the West women are treated as sexual objects, and dismissed workplace equality for men and women, declaring that “we should set aside this notion from our thoughts.”

Rouhani responded to Khamenei the next day. In a speech on the occasion of Women’s Day in Iran he said that “Women must have equal opportunity, equal security and equal social rights” with men. Then on May Day, Rouhani said: “I reject gender-based discriminations in the world of workers and production. Our working men and women must have equal rights.”

Khamenei has always advocated tight control of the government over books, whereas Rouhani has pushed for the state to roll back its censorship. During the opening ceremony of the Tehran International Book Fair, Rouhani said, “We should provide the necessary space for [the people] writing books without any worries [for censorship], and let what is on the people’s hearts and minds find its way onto the paper. The government is not after state censorship.”

But Equally Major Setbacks

With just a few few exceptions, Rouhani has been unable to secure the release of political prisoners, most of whom are leaders and supporters of the Reformists and the Green Movement. In particular he has failed to convince Khamenei to end the house arrest of the Green Movement’s leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi, his wife Zahra Rahnavard, and former Speaker of the Majles, Mehdi Karroubi.

Over the past year the judiciary has executed hundreds of people. Although the vast majority were common criminals who had been convicted before Rouhani’s presidency, much of the Iranian public favors the abolition of capital punishment. The executions have also led to protests by credible international human rights organizations. And while state pressure on opposition political activists has lessened a bit, the political atmosphere is still repressive.

The fact is the judiciary is controlled by the hardliners and Khamenei, not Rouhani. The hardline judiciary chief Sadegh Larijani has gone out of his way to emphasize that nothing has changed since Rouhani’s election. Although Ali Younesi, a senior adviser to Rouhani, has said that the government is unhappy with the accelerated pace of executions and considers them politically motivated, Rouhani himself has been quiet about them.

While the judiciary enacts the executions, Rouhani is not entirely without recourse. He could use his power as the executor of the constitution to issue a constitutional warning to the judiciary, which would embarrass Larijani and put the judiciary chief in a defensive position. But Rouhani has refrained from doing so. Many believe that Rouhani does not wish to confront such issues, until he can resolve the dispute over Iran’s nuclear program and improve the economy significantly.

Hardliners Aiming to Thwart

The hardliners have been attacking Rouhani fiercely on two fronts: in the cultural arena and over nuclear diplomacy. Hardly a week goes by without Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi, the hardline reactionary cleric, attacking the President and calling him a sell-out. Yazdi’s followers in the Majles, known as Jebheh Paaydaari (Endurance Front), have led some of the ugliest attacks on the President, accusing him of ignoring Iran’s nuclear rights, and even begging the United States in some cases. Tehran mayor Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, a former Revolutionary Guards commander who is close to the hardliners, has opened a new front against Rouhani by ordering gender segregation in Tehran municipality, separating female and male co-workers and calling on the government to follow suit throughout the civil service. Rouhani’s senior aides have rejected the idea, but pressure has been mounting on the government.

Rouhani must explain to the nation that those who oppose his nuclear diplomacy are prizing their own interests above the nation’s. He must reveal to the public the immense wealth accumulated in the hands of a few who took advantage of economic sanctions to enrich themselves in the ensuing black market for sanctioned goods. He must point out that Qalibaf’s initiative is purely political, since he has been Tehran’s mayor for nine years, but only now suddenly recognized the importance of gender segregation. He must declare that the impeachment of his ministers by the Majles hardliners is only due to their worries about their own political and economic power and future. As the scope of the corruption becomes clearer, the hardliners will step up their efforts to undermine and even topple his administration to stop the revelations.

Where things stand today, Rouhani is overseeing a fraught, partisan political climate, in which he is constantly attacked by his foes but refrains from confronting them with any real force. The nation expects to see him stand up to his political opponents but is disappointed at every turn. A year into all of this, Rouhani’s performance stands decisively mixed: some successes, some setbacks, but most of the time, reflecting a leadership style that is far more cautious than necessary.

Photo Credit: Asia Society

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments