The world’s attention this week was fixed on President Hassan Rouhani at the United Nations, but it was the Iranian leader watching at home whose politics and worldview informed the president’s address and directed each negotiation Iran’s diplomats conducted on the sidelines. The Islamic Republic’s Constitution grants Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei ultimate and final say over virtually every matter of governance, rendering Iran’s executive symbolic and influential but hardly the true head of state.

Khamanei underwent prostate surgery last month, once again kindling the rumors about his health that have been circulating in Iran for at least 15 years. Although the surgery was apparently routine, the fact remains that Khamenei is 75 and the question of his successor grows more relevant each year. Though little noticed in the West, there has been much behind the scenes maneuvering by hardliners, particularly in the Assembly of Experts, the Constitutional body that appoints the Supreme Leader and is intended to monitor his performance. We explore here the most likely of Khamenei’s potential successors, their political background, and what they might mean for Iran:

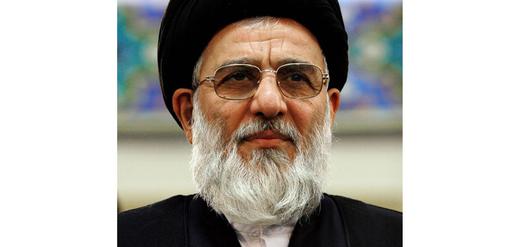

Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi

Ayatollah Sayyed Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi served as judiciary chief from 1999-2009, and is intimately close to Khamenei, even acting as his mentor. Although some conservatives have claimed that Shahroudi was born in Iran, the fact that he was born in Najaf, Iraq, in 1947, is largely indisputable and is perhaps the greatest point in his disfavor, in terms of successor potential. Shahroudi received his theological education Najaf, for a time led the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, one of the two key Shia militias Iran funded and trained to oppose Saddam Hussein.

Shahroudi is a traditional conservative, and is often described as brilliant by his peers to describe his Islamic knowledge. When he was appointed the judiciary chief, Iran was in its reform heydays under the reformist President Mohammad Khatami. Upon appointment Shahroudi spoke about “judicial reforms,” which gave rise to the hope that he would depoliticize the judiciary.

Shahroudi did implement some reforms, putting a moratorium on the punishment of stoning (the practice has been reduced, but has not completely ended); decriminalized certain offenses, and proposed limited amendments to family law in favor of women. He also restored most of the structure of the judiciary that his predecessor, cleric Mohammad Yazdi, had dismantled and made the system more efficient.

But, Shahroudi was ineffective in ending arbitrary arrests of political activists, journalists and human rights advocates; cruel and inhumane treatment of prisoners, which is often accompanied by torture; biased, and often totally unlawful trials, etc. He did not try or was unable to do anything about the arbitrary closure of hundreds of newspapers, weeklies, and monthly publications during his reign as the judiciary chief. After he stepped down from the judiciary, Khamenei appointed Shahroudi to the Expediency Discernment Council, another constitutional body that acts as advisor to Khamenei; Shahroudi is also a member of the Guardian Council.

If Shahroudi were to be appointed the Supreme Leader, he would perhaps enact somewhat more moderate approaches to both domestic and international issues than Khamenei, as he is not close to the radical hardliners. As a recognized Islamic scholar , Shahroudi would have the authority that Khamenei lacked when he came to power, and that standing could enable him to pursue some modest reforms.

Mojtaba Khamenei

One of Ayatollah Khamenei’s six children, Mojtaba was born in 1969 in the holy city of Mashhad in northeastern Iran. After the 1979 revolution Mojtaba and his family moved to Tehran, as his father was part of the new revolutionary elite. After graduating from high school Mojtaba began his theological studies. His first teachers were his own father and Hashemi Shahroudi. He moved to Qom in 1999 to study and joined the ranks of the clergy, taught there by such conservative and ultraconservative clerics as Ayatollahs Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi, Lotfollah Safi Golpayegani, and Sayyed Mohsen Kharrazi. He is also very close to Ayatollah Abolghasem Khazali, an ultra-conservative cleric. Both Khazali and Mesbah Yazdi are believed to belong to the Hojjatieh Society, a right-wing religious organization founded in the 1950s and banned by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1983.

Mojtaba Khamanei exerts great influence on the Basij militia and other right-wing paramilitary groups. He has been linked with such forces through three prominent hardliners; one, up until recently, was Ayatollah Aziz Khoshvaght who died last year, and whose daughter is married to Mostafa Khamenei, Mojtaba’s older brother; Saeed Emami, the notorious figure who was responsible for the infamous Chain Murders was a follower of Khoshvaght; Mojtaba Khamenei was also a friend of Emami, and traveled with him to Britain in 1988. Khoshvaght was influential in the affairs of Ansar-e Hezbollah, a radical right-wing paramilitary group.

The second link between Mojtaba Khamenei and the paramilitary groups is Brigadier General Sayyed Mohammad Hejazi, a former commander of the Basij militia and currently a deputy chief of staff of the armed forces, an ultra-hardliner who functions as one of Mojtaba’s closest aides and supporters. The third link between Mojtaba and the paramilitary groups is through hardline cleric Hassan Taeb, who is close to Mesbah Yazdi and heads the Ammar Headquarters, an ideological center of the hardliners. Mojtaba Khamenei also has close ties to senior hardline officers of the Revolutionary Guards.

It is widely believed that Ayatollah Khamenei is grooming Mojtaba to succeed him. This view is bolstered by the efforts of the Supreme Leader’s allies to to fill the ranks of the Assembly of Experts with younger clerics who are loyal to Ayatollah Khamenei, and might play a decisive role in appointing the next Supreme leader.

If the younger Khamenei were to be the next Supreme Leader, given his close association with Iran’s most extremist forces, he would most likely promote an extreme radicalism, pushing Iran back into the isolated, pariah state status of the Iraq War and Ahmadinejad years.

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

As a constant fixture of the ruling elite ever since the 1979 revolution, Rafsanjani needs little introduction. He has been a two-term president, speaker of the parliament, commander of the armed forces during much of the Iran-Iraq war (a post that was given to him by Khomeini), Chairman of the Assembly of Expert, and of the Expediency Discernment Council. He is still highly influential, is an ally of President Hassan Rouhani, and has wide support among the senior clergy. But he is also 80 years old and despised by the hardliners. Ever since the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as the president in 2005, the hardliners have been attacking Rafsanjani and have sought to strip his political influence. Ahmad Jannati, Secretary-General of the Guardian Council called him a dog and counter-revolutionary, while Mesbah Yazdi recently referred to him as a “smuggler.” His daughters, Faezeh and Fatemeh, and son Mehdi Hashemi have all been prosecuted, and many high-ranking IRGC commanders are fiercely opposed to him.

Rafsanjani has always been a pragmatist, and over the last several years his views have gradually become closer to those of the reformists. As Supreme Leader he may try to democratize the system somewhat by enacting his old proposal that, instead of a Supreme Leader, there should be a council of five major grand ayatollahs, diluting the absolute power that the Supreme Leader has enjoyed.

Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi

Referred to in Iranian politico circles as ‘Mesbah,’ Yazdi was born in Yazd in central Iran in 1934. He received his theological education in Qom, studying with Ayatollahs Mohammad Taghi Bahjat Foumani and Sayyed Mohammad Hossein Tabatabaei. Graduating in 1960, Mesbah himself is considered an expert in Islamic philosophy.

In 1964, a religious school was founded in Qom by Ayatollah Sayyed Mohammad Hosseini Beheshti (1928-1981), a key aide to Khomeini and the first judiciary chief after the 1979 Revolution, Ahmad Jannati, and others. Originally called the Montazerieh School, it was later renamed the Haghani School after a wealthy merchant from the bazaar, Haj Ali Haghani Zanjani, granted the school a sizable endowment. Mesbah was a junior partner in the school and taught there from 1966-1976. Unlike students and disciples of Khomeini, Mesbah, refused to participate in the struggle against the Shah. He left the Haghani School in 1976 and joined another highly conservative religious school in Qom, Dar rah-e Hagh. Khomeini had very frosty relations with Mesbah, never appointed him to any position, and never recognized him as an ayatollah.

After the Revolution, many of the Haghani graduates were brought into the judiciary. After Khomeini passed away in June 1989, Khamenei began purging the political system of the leftist clerics who were close to Khomeini and replacing them with right-wing ones. Many of them were graduates of Haghani School. That made it possible for Mesbah to gradually become more visible and active, spreading his influence. Such hardline clerics as Ali Razini, Ebrahim Raeisi, Ali Mobasheri, and Mostafa Pourmohammadi, who played leading roles in the execution of about 3800 political prisoners in the summer of 1988, are all graduates of Haghani. With the exception of the current one, Sayyed Mahmoud Alavi, every minister of intelligence has been a Haghani graduate.

Mesbah and his followers are the most outspoken critics of the Reformists and supporters of the Green Movement. He once declared of political reform that "injecting such ideas is like spreading the AIDS virus." He also declared that ‘Islamic Republic’ is a contradiction in terms, as a truly Islamic government does not hold elections. Mesbah has consistently espoused violence against his opponents, and has said that he believes trials are not needed to convict and execute offenders.

Although Mesbah is old, he is still very active. He is also close to many IRGC commanders and meets with them on a regular basis. His supporters have formed a political group, the Jebheh Paaydaari [steadfast front], and are fierce critics of the Rouhani administration.

If Mesbah were to be appointed as the Supreme Leader, his approach and policies would be similar to those of Mojtaba Khamenei. He is an extremist conservative and if there is a major religious figure in Iran whose views are similar to those espoused by extremist Islamic groups in the Middle East, such as ISIS in Iraq or the Taliban in Afghanistan, it is Mesbah.

Hassan Khomeini

Hassan Khomeini is a grandson of the founder of the Islamic Republic. His father Ahmad Khomeini was very close to Ayatollah Khomeini and, together with Rafsanjani, played a key role in the rise of Khamenei to the post of the Supreme Leader. But, he later became a critic of Khamenei, and is believed to have been killed by Saeed Emami and his gang as part of the Chain Murders. Born in 1972, Hassan Khomeini became a cleric in 1993. His only official post is being the caretaker of his grandfather’s mausoleum. He was a critic of Ahmadinejad, has criticized the intervention of the military in politics, supported Mir Hossein Mousavi’s call for cancelling the rigged presidential election of 2009, and is considered a moderate. He is also close to Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami. Though he is considered a long shot, he cannot be discounted completely.

If Hassan Khomeini were to be promoted to the Supreme Leader, he would follow in the footsteps of Rafsanjani, Khatami, and Rouhani in trying to moderate the political system by providing more freedoms while preserving its Islamic character.

But Who Stands the Best Chance?

Among the five potential successors, Hashemi Shahroudi probably has the best chance of succeeding Khamenei. Mojtaba Khamenei is not recognized as a senior religious figure, neither in the eyes of the public nor the religious establishment, and he has never held any official position. It is only because of his father and his closeness to the hardline IRGC officers that he is even discussed as a potential successor. Mesbah is too radical and is despised by most senior clerics in Iran. Under normal circumstances, Rafsanjani should be the likeliest successor to Khamenei, but his deteriorated relationship with hardliners means that today they are wholly opposed to him having a major political role. Both he and Hassan Khomeini can rise to power, but only if the senior clerics are unified and publicly call for their appointment.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments