Hamid Baeidinejad, Iran’s ambassador to the United Kingdom and a former nuclear negotiator, has recently had a lot to say about Iranian asylum seekers on Instagram, Telegram and Twitter, as well as about human traffickers who help them escape Iran. But by closing his eyes to why Iranians choose to migrate, particularly through illegal means, and by ignoring social, political and economic ills inside Iran, Baeidinejad has turned the issue of large numbers of people wanting to leave the country into a discussion about Iranians being deceived by international traffickers. However, if he wanted to, he could reach a fuller understanding of the reasons why people want to leave the Islamic Republic — all he needs to do is take a cursory glance at the country’s policies and the problems and ills that Iranian society has to cope with because of them.

Baeidinejad writes that international traffickers, for their own benefit, encourage people to immigrate illegally and put their lives and their property in danger. It seems as though, in his view, traffickers roam the streets and social networks like religious missionaries and openly proselytize, despite the fact that everywhere in the world human trafficking is a crime and can lead to heavy punishments. In such a situation, why would a trafficker behave like a missionary and unmask himself?

Baeidinejad also reports that in the past two years 260 Iranians who had entered the United Kingdom illegally have returned to Iran after going to the Iranian embassy in London. Does Mr. Ambassador know how many more besides these voluntary returnees are currently in Western Europe? How many are on their way? How many more inside Iran are thinking about leaving their country behind?

Over the last eight months I have been traveling along some of the most-used human trafficking routes, from France and Austria to Germany, Greece and its islands, and Turkey. I traveled very close to the Iranian border and talked to new arrivals in Turkey. I asked them about the dangers that they faced along the way and the routes that they took, and they told me their stories without holding anything back. The number of Iranian refugees and asylum seekers is undoubtedly beyond the imagination of Mr. Ambassador.

Refugees Are Lazy!

In his statements, Baeidinejad mentions that legal immigration has been restricted due to economic and social factors and that illegal immigration has been boosted by human traffickers’ “search for profit.”

“Contrary to expectations,” he writes, “in Iran the illegal immigrants are young and are members of middle- and upper-class families who lack higher education or professional training and who embark on illegal immigration to live under conditions that they think are better because of their social and psychological tendencies to live in the West.” He has also written that “Many [illegal immigrants] fall into addiction and indiscretion to forget about these conditions.” He then contrasts these people to those who he described as hardworking classes that have advanced through education or by pursuing a profession and have been successful in their lives.

Without adequate information, Mr. Ambassador has concluded that, not only do international traffickers promote their services, but an immigrant or asylum seeker who has not achieved success because he is not a hardworking person leaves his homeland and ends up a vagrant in the streets of Europe, and uses a trafficker to get there. Then the immigrant preaches despair by saying that in the West one must fight for a job and the competition is fierce.

Of course, Baeidinejad does not explicitly say that Iranian immigration is limited to brain drain, because it is no longer only the educated who leave Iran. On the routes used by human traffickers, one comes across people from all walks of life.

Let me begin with political refugees, whom I came across and talked to in my travels — both those who many, many years ago reached Europe illegally and those who are still on their way. There are political activists who started their perilous illegal journey soon after the birth of the Islamic Republic, and who still tremble when they remember those moments when they confronted death. I talked to Facebook activists who had been imprisoned in Iran. I talked to civil rights activists like those who had launched the “Wall of Kindness” campaign for people to donate clothing to less fortunate people. I talked to Gonabadi dervishes who left their homeland after the events of February 2018. I talked to students who have left Iran over the last 10 years. They all had to resign themselves to traveling illegally because after coping with prison and torture they did not feel safe in Iran. None of them had passports and, therefore, could not save themselves from prison and torture by getting a simple tourist visa. They had no choice but to be smuggled out of Iran.

Where Domestic Violence Is No Crime

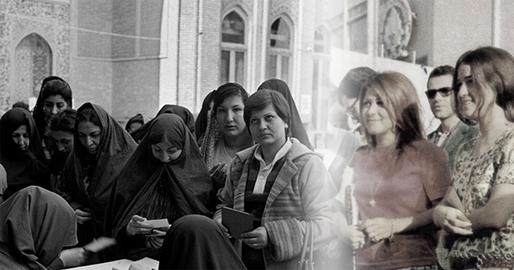

Let me say something about social refugees. On the routes I traveled, I saw many women, victims of domestic violence, who set out all by themselves or with their kids, choosing an uncertain life in exile to save their lives. The ambassador knows full well that domestic violence is not a crime in Iran. Family life in Iran is still considered a private domain and because of this women who are victims of domestic violence are imprisoned in this family life, and are tortured but have no way of taking their cases to the court. Mr. Ambassador is quite aware of how difficult it is for women to prove to Islamic Republic courts that they need a divorce because their husbands threaten their well-being and their lives.

Let me talk about LGBT refugees — a social group that has no standing in the Iranian society and Islamic Republic authorities even deny that they exist, a group that faces prison and even death because of their sexual orientation. They would rather escape to Turkey and suffer the bigotry and humiliation there than to stay in Iran. The painful stories that this group tells of inhumane religious laws in Iran are so shocking that probably Mr. Ambassador cannot bear to hear them.

Kids Living in Danger

Let me tell you about the children who are holding the hand of their mothers, their fathers, or both on the smuggling route. They not only see the violence with their own eyes, they live it. Many a child has told me their stories of traveling this route, in excitement or in pain. They have told me about the death of their fellow travelers, of spending hours and hours in the trunk of a car, of going through mountains and valleys in cold and in snow, of beatings from traffickers and even violence from their own exhausted parents. Parinaz is a seven-year-old girl who lives with her mother in Greece at the home of their trafficker. When I asked her if she would like to return to Iran she said no, but she would like to return to Turkey and go back to school.

I can talk about religious converts, men and women who were forced to leave Iran because of their conversion. Why should they remain when the Islamic Republic calls them “apostates” because they have changed their religion from Islam to another faith and threatens them with execution, and when many converts have been thrown in jail? Let me talk about the Baha’is, people who, because of their religion, have lost their rights and have been prevented from getting ahead in life by orders from the leaders of the Islamic Republic. Does Mr. Ambassador ever ask himself where in Iranian society this wave of refugees comes from?

The Dream that Froze to Death

Let me talk about the artists. The musicians who decided to leave their homeland because they had to deal with all kinds of Islamic prohibitions and censorship, whose instruments were broken and the only choice left to them was self-censorship. Pedram Safari froze to death outside a refugee camp in Serbia and was one of these young people who dreamed of music. And I can talk about actors —those who escaped to Turkey and work with the networks that the Islamic Republic calls “hostile,” those who are now in Greece, and those who reached their intended destination and are now trying to rebuild themselves. Why shouldn’t they nurture dreams of freedom when in their own country censorship and self-censorship runs wild?

Let me talk about economic refugees — those who, with or without higher education, went into business but went bankrupt due to lack of economic stability in Iran, corrupt deals, sanctions that have paralyzed the Iranian economy and many other factors, and were forced to leave their country. Perhaps Mr. Ambassador would find it interesting to hear the story of a woman whose husband went bankrupt and afterward, their son was physically punished repeatedly in school for neglecting his studies. She now lives in Athens at the home of the trafficker, hoping that her son will have a better fate than her husband.

Breaking the Law

It goes without saying that there are those that break the law among the refugee community. Some of these people who break the law, of course, have served time in Iranian prisons. Does Mr. Ambassador know Sajjad, a 25-year-old young man who arrived in France a year and a half after he escaped Iran? He seeks asylum and introduces himself as a felon because he drank liquor and drinking alcohol in Iran is illegal. Does Mr. Ambassador know that the hands of this young man still bear the imprints of the shackles that he wore in the detention center? Does he know that when this young man pulled his shirt up you could still see on his body the evidence of the lashes that had received? As I was walking with Sajjad in a shopping mall we passed a bar. “In Iran they tell you that if you drink alcohol you are a criminal,” he said. “They will throw us in jail. But now here I have peace. I drink and nobody bothers me.”

Among these refugees there are also “piggy backers” — those who carry goods across the border on their backs, legally or illegally, to make a meager living — those who could not afford to pay their wife the promised dowry, or the contractors who worked for the Revolutionary Guards but were cheated of their money and threatened with prison. And then there are children who have to work, like a 10-year-old who was sold by his father.

Now let me tell you about dangers along the escape route. Long treks in extreme heat and cold, mountainous paths and slopes where one slip can end in death, sea voyages in unsafe boats and facing death, hunger and thirst for days and nights. And there are dangers such as being taken hostage by traffickers, humiliation, insults and beatings by traffickers and border guards, a lack of even the most basic facilities for hygiene and medical care in refugee camps and, not least, rape and sexual harassment, especially directed at women and LGBT groups. And these are only some of the dangers that refugees willingly accept only because they do not feel they can live in Iran anymore.

Hope of Gaining Back Some Power Over Their Lives

Refugees and asylum seekers put their lives in danger to escape the realm of the Islamic Republic and to enjoy social, economic and political freedoms. Their everyday life can be summarized by their dream to reach their destination. As many refugees have told me: “When you are in the hands of traffickers, you no longer have any power of your own.”

They put their “life and property”, as Mr. Ambassador says, in the hands of traffickers so that, perhaps, they can realize their dream after surviving all these dangers and threats.

Now Mr. Ambassador — who is still an advisor in nuclear affairs and who was once Iran’s representative at the United Nations Human Rights Council — disregards the reasons as to why Iranians leave their homeland. He advises them not to worry, there are no problems and they can return. Of course, there are some who cannot take life as a refugee and go back to Iran. But there are many more Iranians who risk death to acquire the social, political and economic freedoms that their own country denies them. Mr. Ambassador easily shrugs off the Islamic Republic’s responsibility, but perhaps he has forgotten that Iranian border guards are ordered to shoot people who try to cross the border? Many a child, woman and man have told me about coming across bodies on the border paths or about running far and fast so that they can escape shots fired by the border guards.

Perhaps Mr. Ambassador, who once articulated “Islamic” human rights for the United Nations, can ask himself and other Islamic Republic authorities: Who is responsible for the wave of Iranian refugees who have despaired of having a decent life in their own country? Who is responsible for the death of Pedram Safari? Who is responsible for the death of Iranian refugees on the borders of Iran? Are the human traffickers the only ones responsible for violence along the perilous journey into exile? What happened to these refugees in their own country before they left it behind?

The views of the author are not necessarily those of IranWire. IranWire welcomes all views in its blogs section

More on Iranian Refugees:

“A Long Journey to Turkey — to Save my Mother”, December 7, 2018

An Exhausted Mother: I Regret Seeking Asylum, December 4, 2018

The Love of my Child kept me Alive in the Mountains of Iran and Turkey, November 30, 2018

Prison, Asylum, and a Family Torn Apart, November 20, 2018

An Ex-Police Officer’s Illegal Journey to Turkey, November 16, 2018

From France to Turkey: Human Trafficking and Asylum Seekers, November 13, 2018

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments