Sepideh Gholian is a 25-year-old civil rights activist and journalist who was arrested during the labor protests of Haft Tappeh workers and sentenced to 18 years in prison. Her book, Tilapia Sucks the Blood of Hur al-Azim, tells the story of her detention at the Dezful Intelligence Detention Center and Sepidar Women's Prison in Ahvaz.

In these 19 stories, Gholian paints a meticulous picture of her horrific experience. On one hand, we directly encounter the face of oppression. On the other, we engage with the fates of others whose names, lives and imprisonment might otherwise be doomed to be forgotten and denied.

IranWire has previously published Gholian’s book in its original Persian and is now serialising the collection in English, while its author has been returned to Iran’s notorious Evin Prison. The stories are translated by Zahra Moravvej.

The first meeting: cabin visitation

I love visitations since I can see the pieces of my heart, the ones that I feel have been cut away from me with scissors. We are consigned to separation. Although I have been beaten at home 67 days before the visitation and I can’t walk properly, I yearn to see them again. The visitation is like a breath of freedom, with the strike ban that has been imposed on me in prison.

I am so eager to see them that I can't sleep. I write a letter to them; I assure them that everything here is ok and this is an extraordinary experience for me. I also write that our perception of the prison needs to be altered. I write that the name of our war is Daffodil, and I write about Shabnam Lak, a girl who has been here for eight years.

Mehdi! This girl has been here for more than eight years because she transported some drugs. But she keeps a collection of perfumes under her bed: oily perfumes that she bought from the prison market.

I write about her desire for life.

Once I asked her, “How did you survive in prison when you were sentenced to death?"

She said, ‘" survived with the help of the Alibaba’s heart-shaped cookies! I cut them in half and would give one half to Neda, my cellmate. This profound love kept me alive and eased the situation. I dreamed of being free and baking a heart-shaped cookie. Neda was hanged so I must put half on her grave."

The tears fall. Mehdi! You can scarcely believe such a wonderful person is here. She is the head of the ward too. Mehdi, you won’t believe how happy I am here. I know it’s a cliché, but I ask myself; we have lived for so many years, how is it possible that we were not aware of such a place?!

Then I write about the kids in prison.

My dear brother! We loved each other, we grew up and lived with each other, and all the while we just hurt each other. Even though you’ve crippled me, I am dying to meet and hug you. I think we must use this chance to understand each other better. Mehdi! Shabnam is very beautiful. I can’t wait to be free and bring her home. I think you’ll like this fountain of excitement and emotion, who by the way, plays volleyball too.

Shabnam has given me a blue scarf and a white chador. “Wear these for the visitation. Your family is waiting for you. Look glamorous! I know tomorrow is a cabin visitation. But speak with Mrs. Mirza and tell her that it’s some months since you saw your family. Maybe she’ll let you visit your father in person."

Morning means forced prayer, a forced morning program and the opening of the yard. And I am awake until morning. The anticipation of wearing a scarf that has been here for eight years, but still sings the song of freedom, makes me sleepless.

From 10am onward the ward is jam-packed. They send a guard and disconnect the phones. I have talked with my family the day before, and they told me they are so thrilled to be seeing me that they will sleep outside the prison so they can be the first to enter the visitation hall. Since 9am I stare at the door, waiting to hear my name. Shabnam has told me that at 11am, someone will come into the corridor and read out the names.

1.Khadijeh Asakereh

.

.

.

.

33. Sepideh Gholian

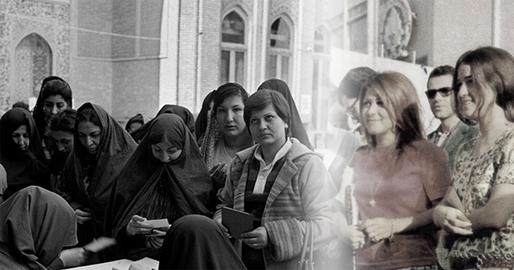

I expected to be the first person and I had begun to feel fed up waiting in the middle of that hubbub. The noise increases, with some crying because their names were not read. Some are sad that they don’t have a visitor, and some like me, with chadors, plastic sandals, covered hair and pale faces, are waiting.

We are all gathered into one place and this orderly anarchy moves through into the security office. We are being inspected thoroughly; in fact, we are stark naked! The co-opted prisoner in there tells us: “To avoid being naked, I haven's seen my family in five years. I have asked them not to come." She is a laborer-prisoner; while inside, the prison authorities allow them to work and in return they are entitled to have minor privileges.

“She is lying!” Khadijeh tells me. “No one is coming to visit her. If they were, after five years you would gladly be naked."

Makieh defends the woman. “Come on! What do you know? She’s telling the truth.”

The duty officer is called Pirayesh. “Convicts!” she yells. “Shut up and we’ll get you inspected quicker! Why can’t you behave?”

There is a strange contrast between the inside and outside of the prison. Outsiders perceive the prisoners as criminals, and the prison workers as saviors. But if you take just one step over the threshold, everything changes. Here, the convicted murderer is not the killer. Here you perceive the difference between the one who killed someone accidentally or out of anger on the one hand, and the authorities who are constantly killing, calmly and taciturnly, on the other.

We have been humiliated since the morning, just because we want to see our dear ones. They have inspected the sandals and chadors. They have assaulted us in many ways. The cycle of disgrace is endless. They take us all to the cabin visitation along with the men. An in-person visitation with your father or brother is also banned, unless the head of the prison agrees.

Today Mrs. Mirza is absent so I can’t ask for permission to see my father and brother in person. I am a newcomer, so I have just asked my family to bring some stuff that I need. They take my letter and say that it should be read by the security team first, so I crumple it up and throw it under my feet. It takes yet another hour to inspect us and lead us to the yard.

It is close to 1pm. We have gone through the gruelling inspection process and now we are close to the exit. The ones with more experience warn, “Hold up, it’s not over yet!”

I am nervous. They keep us under the hot sun, telling us we should be all set. Then the soldiers open the iron doors into the visitation hall.

So many women in white chador! Pirayesh shouts, “Heads down, convicts! The men shouldn’t see you!” Two hundred women in chador and plastic sandals, with their heads down, start forward. Dust rises into the air and a soldier shouts out, "Look, a herd of sheep!"

Some start laughing; others cry. Some are like me, confused, and just eager to see their families. Pirayesh and several soldiers accompany us. She approaches me: “Sepideh, dear! You’re not like these criminals and shouldn’t be treated the same way. Look at your socks. The soldiers are watching and laughing at you. A good girl must wear dark-colored socks!”

All I hear is “criminal” and “Sepideh dear". I don't say anything. Now we are at the door of the visitation hall. Maria keeps screaming. It’s a strange combination in here: the young, the old, children. This bizarre new configuration confuses me. We rush into the hall; Maria falls and we stampede over her. I see the cabins. My father, Mehdi, Meysam and Arashk are in the third cabin.

We scream. My father hits himself on the face, and Mehdi hits the glass of the cabin. I pick up the phone receiver. The whole night I plucked and shaped my eyebrows, I wore the most beautiful scarf and chador that Shabnam could find, to surprise my father. But the rush and the behavior of the prisoners have shocked him. He keeps beating himself on the face: “I was wrong! You don’t deserve to be here.”

I am surprised too! Why have I forgotten the eyes of outsiders? Why do I perceive beauty like the prisoners do? The handset is flowing between the four of them. At one point they cry, at another time they laugh, and we exchange news and reports. At the end of each sentence, my father asks, “Is the handset bugged?" But he doesn't wait for my answer and carries on relaying their news. Twenty minutes of visitation comes to an end, and Pirayesh shouts," Ladies! Put the handsets back, or you’ll be barred from visitation."

I put back the handset and continue talking with hand signals. Mehdi goes to the other side of the hall, which is fenced off. We can get closer to each other there. My small finger pokes through the fence and my brother kisses it. The soldier shouts at us and we step away from each other.

Don’t look for an excuse to fall in love! I think. Sometimes there is a blossom on the tip of a cactus thorn that will light up your life!

Everybody is crying and screaming. It is a strange situation. I can't call it a warzone. No; there should be a new term for this.

We return to the ward with the same difficulties as before. Although it was a cabin visitation and we didn't get close to our visitors, we are still inspected again: “Get your clothes off, do the push-up and then the vaginal examination."

The same laborer-prisoner looks at me again and says, “I swear on my father's eyes. Because of this inspection alone, I have had no visitation for five years."

It’s 3pm by the time I come back onto the ward. I am tired, but I have been summoned by the duty officer. She gives me the stuff that my family brought me: books and colorful clothes. Pirayesh laughs and says, “Sepideh dear! You don’t belong in this place. Look at these strange things.”

She doesn't let me hang onto the books. First, they should be checked with security.

The second meeting: in-person visitation

Mrs. Naderi calls me three days before the visitation and hands me three books. “When you’ve finished reading these, return them to me. If I hear that you’ve given any of them to your cellmates, you will be banned from having books. I am giving you these so you’ll stay in your bed and stop chatting with other prisoners. They are criminals. You are different. One day you’ll understand this for yourself."

What I said in response is not important. Imagine that I said “You’re right,” or else, that I punched her in the face. What I said in that moment, carrying three books, with blue hair and baggy pants, is irrelevant. Should I acknowledge the discrimination and talk about it? Should I spit in her face? I don’t know.

The process is the same as the first visitation the previous week. I endure the long night by reading El Aleph by Borges. I have gone over a thousand times the conversation between me and Mrs. Naderi in the security office (the content of which does not matter). It’s as though I am consulting with Francis Bacon, Soliman and Plato, and being told: “Soliman has nothing new to add. But as Plato had said, all knowledge is nothing but remembering. Soliman also has passed his verdict, saying that this is nothing new, but it was forgotten.”

On visitation day, we pass through the same cycle of humiliation, abuse, odd inspections, chador, and... and yet we are all happy.

Today the Arab women get visitation too. Last week they made us cover our faces with chador so no one would see us, because we were criminals. This time, the Arab women cover their faces with handkerchiefs. The duty officer chastises them, saying “We know you are all members of ISIS. Why do you cover your faces like this?”

Sakina, carrying her child Fatima in her arms, begins to cry. She looks at me: “Since we were young, we have been told to wear burqa. We are not used to seeing our own faces in the mirror. What does it have to do with ISIS?"

This week we all keep our heads and faces held high in the visitation hall. I am carrying Fatima. For in-person visitations, we store up water the night before. Each day we are allowed a bottle of water, and so we fill the bottles for our families and keep them in the fridge. But since Fatima feels thirsty a lot, her mother can’t keep her share of the water in the fridge. Sakina has asked me to stay close to her, and to give water to her family if they become thirsty.

“A bottle of water each isn’t enough?” I ask.

“Yesterday, there wasn’t any water in the prison. So I used my share to wash her with after she went to the toilet.”

We all rush into the hall. There aren't enough chairs, so some people have a mat. There are some people standing and others sitting on the floor.

I talk eagerly with Samaneh. My mother and Zahra are confused, and keep asking, “Why is she here? What did she do?”

It is so crowded. The guards keep humiliating us and our families, but we don’t comprehend them. We also don’t realise that I and Sakina have lost each other in the crowd, and her child is weeping, because she is thirsty.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments