Even though he’s dead, the great filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami is still making waves in Iran.

He actually died in Paris, but filmmakers and artists here blame his death on a traditional reluctance by Iranian doctors to tell patients how seriously ill they are. If Kiarostami had known the truth about his cancer, he might have gone abroad for specialist treatment early enough to save his life. The Medical Association of Iran denies any wrongdoing.

Even now, many of his fans don’t want to accept that he is gone, but his tombstone in North Tehran is undeniable – a white slab of marble engraved with a lone tree.

It’s a reference to his explanation of why he did not leave Iran after the Revolution. If you transplant a tree, he said, “from one place to another, the tree will no longer bear fruit....If I had left my country, I would be the same as the tree.”

After his death, a BBC Persian documentary revealed that he actually planted a lone tree on a hillside as a focal point and natural “set” for his films Through the Olive Trees and Life and Nothing Less, where local people he’d recruited acted out his narratives.

These movies not only explored big themes – love, self-respect, social pressure – but also real events, like the catastrophic earthquake in the early 1990s in Roudbar, where Through the Olive Trees takes place. I attended both his memorial and his funeral. They received a lot of media coverage, but let me share some of the details that didn’t make it into the news.

For those who know Tehran, it took place just behind the Laleh Hotel at Kanun, the Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults. That’s where he ran the film department and got his start as a director.

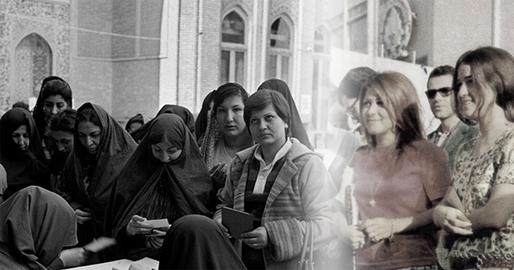

Five thousand people gathered to pay their respects, to remember him, and to grieve. There was none of the rote slogan-chanting that sometimes breaks out at large official gatherings in Iran. Thank goodness. Kiarostami would have hated that.

Instead, one famous actor after another paid homage to Abbas Kiarostami — friend, colleague, guru, mentor, and the first Iranian artist to appeal equally to virtually all Iranians and to Western elites.

Inevitably, some of the speeches were official boilerplate.

Others were deeply sincere.

The celebrated actress Laila Hatami only managed a few words before she burst into tears and had to leave the podium.

Another giant of Iranian and international cinema was there — Rakhshan Banietemad — but bizarrely, he was prevented from speaking because he had helped organize the event.

Parviz Kimiaei , the one-time enfant terrible of the Iranian film world, managed a very few sorrowful words. Daryoush Mehrjoei was so devastated by the loss of Abbas Kiarostami that he could not even make it to the podium.

Asghar Farhadi, who won an Oscar for his feature film Separation, pointed out that Kiarostami had been a trailblazer. He “paved the way for [the rest of Iran’s film artists] to the international silver screen.”

Our national prejudices were on display of course, and I like to think Kiarostami would have been amused. He and his films often put women and their views front and center, challenging official cant in this conservative society. Notably, in his film Ten the main character – the taxi driver — is female and one of the passengers profiled is a woman sex worker.

At Kiarostami’s memorial, though, men and male voices dominated.

After the speeches were over, officials from the Culture Ministry and the House of Cinema led the way to Kiarostami’s burial in Lavasan, the wealthy neighborhood in northeast Tehran where he’d lived. The municipality had put up huge murals and posters along the way and arrows pointed the crowd, which included many celebrities, to the graveyard.

In the following days, the House of Artists, which is situated in the north wing of the former US embassy in Tehran, offered public screenings of all Kiarostami’s films so anyone who had missed the funeral and burial ceremonies could see complete oeuvre — starting with films from the 1960s, right up to the last movie he ever made, Someone like a Lover, shot in Japan.

In the film, a sociology student has an affair with an old man. During the sex scenes, the viewer sees only a blank LCD screen with a Japanese voiceover. In Iran, we understood that Kiarostami was making a point – obviously censoring himself so the authorities wouldn’t censor him.

Back in the 1990s, Kiarostami caused a lot of controversy by pointing out that censorship had a silver lining. It forced artists to be creative, he said.

It’s too late to ask him whether in later years he’d changed his mind. We do know that by 2010, he made a decision to sidestep Iranian state censors by making the film Certified Copy in Europe. The Culture Minister Officials didn’t mention that inconvenient fact at his funeral. Instead, they basked in his reflected glory, spouting eulogies one after the other.

Kiarostami’s public legacy is a collection of revered cinematic treasures. He also, unknowingly, left a smaller private legacy to me.

The way his camera celebrated the drama of the ordinary altered me. To this day, I find myself making little movies in my head about the people and places I observe as move through life.

I offer a grateful salute to the Lone Tree.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments