Abolhassan Banisadr, who served as the first president of the Islamic Republic after 1979, died in Paris on October 9 after a long illness. Until the end, he still considered himself the president of the Islamic Republic because he believed he had been removed from office illegally in 1981, through a “creeping coup d’état”. His critics, meanwhile, long accused him of fostering a “personality cult”.

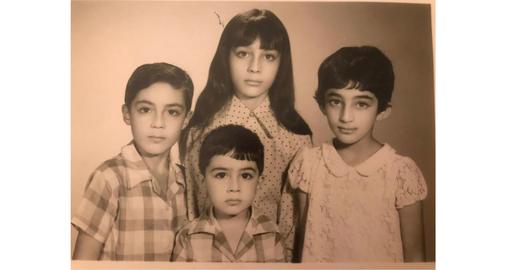

Banisadr was born in March 1933 in the city of Hamadan. His father was Ayatollah Nasrollah Banisadr. He has since said that his father wanted him to become a clergyman, but he refused to go along with it. According to Banisadr himself, he became a republican while in high school – and in college, used to tell people: “I’ll be the first president of Iran.” His friends remember the same thing and say they called him “Monsieur le Président” in jest.

Abolhassan’s brother Fathollah, meanwhile, was a member of the National Council of Resistance, which was formed after the CIA-engineered coup in 1953 that overthrow the nationalist Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. Abolhassan was heavily influenced by his older sibling.

“We were children when we learned from Fathollah about Mosaddegh, and Mosaddegh’s ways,” Abolhassan has said. That said, he was not active in the National Council of Resistance due to being more left-leaning, and has said working with the leftists in those years was a “win” for the National Front.

This was where the differences between him and Shapour Bakhtiar, an ally of Mosaddegh who eventually became the Shah’s last prime minister, first showed. Bakhtiar would later claim that it was Banisadr who prevented Ayatollah Khomeini from appointing him as prime minister after the revolution.

Unlike Bakhtiar, Banisadr wrote, “We said ‘no’ to dependency [on the Soviet Union] but yes to a way of thinking. We aren’t against the membership of somebody with a communist way of thinking in the National Front because everybody has a way of thinking. If somebody is an independent Marxist, he can have a place in the National Front. This is why we accepted the membership of the student supporters of [independent socialist] Khalil Maleki, and the leftists who said they were independent.”

Banisadr played an important role in preparing National Front’s statement in support of Ayatollah Khomeini. He also claimed that it was he who persuaded Dr. Gholam Hossein Sadighi, Mosaddegh’s interior minister, not to accept the Shah’s offer to become his prime minister when the revolution was approaching, with the job falling to Bakhtiar instead.

Banisadr was imprisoned twice in the early 1960s for participating in anti-Shah student protests. After he went to France and registered at the Sorbonne to study finance and economics, he was the representative of Tehran University at the congress of the International Confederation of Iranian Students.

During this time and afterwards, he constantly competed and clashed with Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, a then-close aide to Ayatollah Khomeini. He also competed with Ebrahim Yazdi, who accompanied Khomeini to interviews as his interpreter. According to Banisadr, Ghotabzadeh procured a new car for Khomeini after he arrived in Paris – but Khamenei chose to ride in the car that Banisadr put at his disposal.

Portraying Khomeini as a Believer in Democracy

Banisadr has said he tried to create a “democratic image” for Khomeini because, if the latter had kept repeating what he had said in the past, he would have been stuck in Paris for years. Banisadr was good at presenting economic views that left-leaning Islamic students favored and his book, Monotheistic Economy, proved very popular.

Banisadr also said he was against Velayat-e Faqih (“Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist”): the founding principle of the Islamic Republic. But he had his wife Ozra Banisadr translate Khomeini’s Velayat-e Faqih into French nonetheless. She later said that she was not happy about doing so, but her husband told her Khomeini had evolved and accepted democracy: “I agreed to translate the book,” she said, “even though in my heart of hearts I knew that Mr. Khomeini had not ‘evolved’.”

After returning to Iran with Ayatollah Khomeini, Banisadr was elected to the Constitutional Assembly. When Mehdi Bazargan resigned as prime minister he was appointed as acting finance minister, and acting foreign minister, of the newly-established Islamic Republic. On January 25, 1980, he got his wish and was elected as the first president of Iran.

His most serious competitor for the presidency was the Islamic Republican Party candidate Jalaleddin Farsi. But in the end, Farsi had to drop out of the race after his Afghan origin was revealed.

Banisadr was supported in his presidential campaign by Ayatollah Khomeini’s personal associates, but Khomeini’s students were less than happy with him. Five of them — Mohammad Hosseini Beheshti, Abdolkarim Mousavi Ardebili, Ali Khamenei, Mohammad Javad Bahonar and Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani — wrote a letter about this that became known as the “No Greetings” letter. In it, they objected to Khomeini’s support for Banisadr and to the elimination of the Islamic Republican Party’s candidate, and claimed this move had made the opposition more “brazen”.

Quarreling with the Revolutionary Guards

Banisadr finally became president in February 1980. Not long after that, he began to fall out with Khomeini’s associates and the Islamic Republican Party. His speeches added fuel to the fire: especially one he delivered on March 5, 1981, at Tehran University in which he strongly attacked his critics and the policies they advocated. Among the most divisive issues were the war with Iraq, and Banisadr’s disagreements with the Revolutionary Guards.

When he took over the presidency, Banisadr had wanted to pick Ahmad Khomeini as his prime minister. But Ayatollah Khomeini opposed the nomination of his son. Afterwards, there was uproar at the parliament each time he tried to nominate a prime minister of his own choice. In the end, he addressed the letter presenting Mostafa Agha Mirsalim to “Respected Representatives – not to the speaker or the governing body of the parliament – leading to protests at the parliamentary session of July 27, 1980.

Impeachment and Escape

On June 10, 1981, Ayatollah Khomeini removed Banisadr as commander-in-chief of the armed forces and gave that title to himself. On the same day, Mohammad Jafari, managing editor of Banisadr’s own newspaper Islamic Revolution, was arrested together with two of his friends.

Under pressure from Parliament, Banisadr nominated Mohammad-Ali Rajaei as his prime minister. But the tension did not subside, and the parliamentary caucus known as “Imam’s Line” decided to remove Banisadr from office. The bill to impeach him was introduced on June 16, 1981 and led to disorder in the chamber. A few days later, on June 21, MPs who supported Banisadr and members of the Freedom Movement refused to attend.

Of those present, the vast majority voted “yes” to convicting Banisadr of political incompetence. Just 12 abstained and Salahedin Bayani was the only representative to vote “no”. After his impeachment, Banisadr went into hiding and a while later, escaped Iran together with Masoud Rajavi, leader of the People’s Mojahedin Organization (MEK), while Banisadr’s wife and a number of his close associated were arrested by the Islamic Republic.

After escaping Iran, Banisadr entered into a coalition with Masoud Rajavi and became a member of a new National Council of Resistance. Banisadr’s daughter even married Rajavi, but relations between the two men deteriorated and eventually broke off after Rajavi aligned himself with Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, who had invaded Iran.

Despite a vast propaganda campaign by the Islamic Republic’s officials and media to portray Banisadr as a “traitor”, Ali Shamkhani, deputy commander of the Revolutionary Guards in those years, announced more than once that Banisadr was not a traitor and had wanted Iran to win the war in Iraq.

Iranian media outlets have repeatedly claimed that Banisadr believed Saddam Hussein must be allowed to occupy more of Iran because “we must give land to buy time.” Banisadr, however, denied this, pointing to his own letter to Khomeini of September 19, 1980 as proof. “Every centimeter of our homeland must be defended,” he had written. “A country that loses its land will have nothing to take back.”

After leaving Iran, Banisadr continued publishing the Islamic Revolution newspaper. He had some involvement in revealing the details of the Iran–Contra Affair – a secret U.S. arms deal that saw Iran receive missiles and other arms to free some Americans held hostage by terrorists in Lebanon – and appeared as witness at the Mykonos Trial, when a German court was trying Iranian intelligence operative for assassinating Iranian-Kurdish opposition leaders in a Greek Restaurant in Berlin in 1992.

Banisadr was the last non-cleric to work with Ayatollah Khomeini in Paris. Now, after the death of Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Ebrahim Yazdi, Ayatollah Khamenei is the only one that remains from the first generation of the Islamic Revolution. His role was not as pivotal as theirs.

Related Coverage:

Banisadr: The Optimistic Islamist (1980-1981)

Ebrahim Yazdi, Dean of Iranian Islamic liberalism, Dies at 85

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments