Since this article was published on January 23, IranWire has spoken again with Nosratollah Khosravi-Roodsari. He is pleased that IranWire has told his story, and sent through photographs taken with celebrities during his time in the United States. He is re-adjusting to life back in the States, and asked for his privacy to be respected.

“Yes, he left Iran.” This was the sentence we have been waiting for for the last seven days, in order to bring you this story. Nosratollah Khosravi-Roodsari, also known as Farzad or Fred Khosravi, has left Iran. He is now somewhere in the sky between Iran, his country of birth where he was in prison for almost a year, and the United States, which released seven Iranian prisoners in exchange for Khosravi and three other Iranian-American prisoners. Khosravi has become known as the fourth Iranian-American prisoner released from Iran on January 16, and the mysterious one who didn’t want to leave Iran with the others on the Swiss airplane.

So who is this mysterious man? Journalists flocked to social media to see what they could find out. He doesn’t have a Facebook page or a Twitter account. There was no information available about his arrest or the charges against him. All the American authorities said was that he was an American citizen arrested in Iran.

It was only by chance that one of IranWire’s occasional contributors told us that Khosravi’s former cellmate had expressed his joy at Khosravi’s release in a Facebook post. The cellmate does not want to be identified, and has since removed the post. Khosravi’s tale, as told to us by the cellmate and a family member, is bizarre yet typical of many Iranian prisoners who have been arrested by a paranoid government on security charges. We have not been able to speak with Khosravi, but the following details have been confirmed by three independent sources.

According to Khosravi’s cellmate, Khosravi served in the Iranian military during the 1979 Islamic Revolution. He was a member of the army units that fought anti-regime activists in the northeast of the country a few months after the revolution began. We don’t know why Khosravi left Iran. More than a million Iranians migrated to the United States and other countries in the early 1980s. Khosravi moved to California, which is home to the largest Iranian community in the Diaspora. According to his family members, he worked in the carpet industry as a designer and seller in California and Florida.

Khosravi’s life took a dramatic turn when he unexpectedly became an advisor to the FBI. According to his cellmate, Khosravi told him that he once noticed that he had unintentionally bought a car with stolen parts. He managed to identify the thieves of the stolen parts, and notified the police about his findings. The FBI, he said, was so impressed by his investigative talents that they asked him to work with them on a freelance basis. According to the cellmate, Khosravi insisted during his interrogations in Iran that he was not an FBI employee or an agent, “just an occasional advisor.” Khosravi told his cellmate that his job included visiting car shows and secondhand dealerships to identify stolen cars and cars with stolen parts. The FBI did not reply to our email enquiries about Khosravi. A former FBI agent told IranWire that it is not unusual for the FBI to hire freelance consultants with special talents.

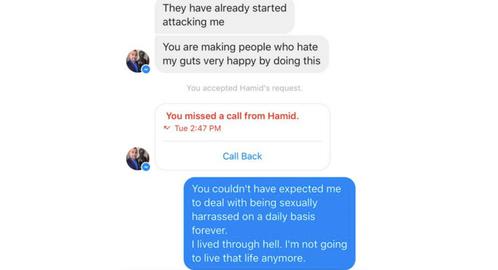

Khosravi went back to Iran in August 2013 to visit his elderly mother in the city of Tonekabon, close to the Caspian Sea. He decided to stay in the country and worked part-time as English teacher. Khosravi, who the cellmate says is now in his late 50s, fell in love with one of his students, a woman in her 20s, and asked her to marry him. The couple was supposed to marry in 2016.

One night, at a gathering with friends, Khosravi saw a report on BBC Persian television about Robert Levinson, a CIA consultant and former FBI agent who disappeared in Iran in 2007. Khosravi sent a text message to an FBI contact indicating that he knew Levinson’s whereabouts. Later, during interrogations and in conversations with cellmates, Khosravi said that he sent the message under the influence of alcohol, which is illegal in Iran. His cellmate and family members say that Khosravi had no information about Levinson’s fate, and had simply lied to impress his FBI contact.

The Iranian government has denied any knowledge of Robert Levinson’s disappearance, a claim that appears to be accepted by the White House. But journalist Barry Meier, author of “Missing Man,” a forthcoming book about Levinson’s case, claims that Iranians were holding Levinson in the country at least until 2011, and were willing to exchange him for unspecified gestures by the US government.

Iranian officials are not known for transparency with regard to the fate of prisoners, as recent cases have shown. Authorities have never admitted to arresting Iranian-American consultant Siamak Namazi. In the case of Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian, who was released in a prisoner exchange last week, authorities never officially declared the reasons for his arrest.

Despite the government’s denial of knowledge of Levinson’s whereabouts, his case seems to be a thorny issue for the authorities. The words “Robert” and “Levinson” are reportedly keywords monitored by Iranian intelligence. All cell phone providers in Iran are either owned by or affiliated with the Iranian government. According to security experts, Iranian intelligence, similar to NSA, collects and monitors millions of text messages everyday. Khosravi’s cellmate and his family members believe Khosravi was under surveillance from the moment he sent his FBI contact a message about Levinson.

“In May 2015, Fred Khosravi ordered a cab to take him to Tehran’s Imam Khomeini Airport to go to the United States. At the airport he was told that he couldn’t leave the country,” says the cellmate. “He was taken away without being told where he was going. They blindfolded him and put him in a Hyundai Santa Fe, the intelligence agents’ car of choice. It’s the very same make of car that I, and other people I know, were taken away in.”

Khosravi’s lawyer said plainclothes security agents charged him with espionage and sending “secret information” to “a hostile government,” meaning the American government. Khosravi was roughed up during the arrest and was taken to Ward 209 of Evin Prison, which is controlled by Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence.

Judge Abolghasem Salavati was in charge of Khosravi’s case. Salavati, who has been nicknamed “the judge of death,” is known for his harsh treatment of defendants in security-related cases. When Khosravi told Salavati that he was drunk when he sent the text message, and just wanted to show off, the judge sentenced him to 74 lashes, the punishment for consumption of alcohol in Iran. The sentence was never carried out.

While in Evin Prison, Khosravi was allowed to speak with family members for one minute a week. Khosravi told his cellmate that his interrogator warned him about telling anybody about where he was. For a long time, Khosravi did not tell his family that he was in prison.

“Whenever he talked to his family from prison, he would say ‘I’m with a client at the carpet store in the US. I need to go’. And then would hang up the phone,” says the cellmate. “The family eventually became angry with him for ignoring them. They didn’t know that Khosravi was in prison." It was only after a few months that Khosravi told a family member that he was in prison. American officials were also notified of his status months after his arrest.

“His trial was supposed to be in April 2016 at Branch 15 of Tehran’s Revolutionary Court, presided over by Judge Salavati,” Khosravi’s lawyer said. Khosravi’s lawyer said she had generally not encountered any obstacles when trying to represent her client, but admitted that the surprise release meant that she had not had a chance to review new developments in his case.

“At the request of Judge Salavati, I did not talk about the case to anyone, but now that the case is closed, I believe there should be no legal prohibition on that,” she said. She says that she was as surprised by Khosravi’s sudden release as she was when she heard he was arrested. “The arrest was the result of a misunderstanding,” she says. “But I’m glad that he’s out of prison now and can go back to his life.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments