Introduction

Of all countries that kill prisoners, Iran has one of the highest profiles. Only China executes more people but, whereas China is secretive about the practice, Iran places itself among a tiny group of nations – notably, Saudi Arabia, North Korea, and Somalia – that kill some prisoners in public. Amnesty International, which opposes capital punishment in all cases worldwide, has pointed out Iran’s unusual method of execution, whereby executioners sometimes drag the condemned upward by their necks from cranes. It noted in a 2013 report that “the authorities appeared to believe that public executions deter crime and protest by spreading fear among those who witness them”.

The organization advances a centuries-old argument that capital punishment does not deter crime. It also makes the case that, “by definition, a person under sentence of death is no longer an immediate threat because he or she is already imprisoned and therefore removed from society”. It warns that Iran sentences people to death based on confessions extracted through torture, and that it punishes “crimes” such as adultery and apostasy, which “should...not be considered crimes at all”. On January 16th, Amnesty reported that Iran had executed 40 people since the beginning of 2014 (killing at least one person in public) and risked making authorities’ attempts to improve their international image “meaningless”.

While the Iranian government might frame executions public and otherwise as symbols of Islamic Revolution or a matter of sharia law, capital punishment continues to decline worldwide, and many societies have successfully challenged the practice through media coverage and legislative reform. Many western countries once conducted public executions from motives of deterrence, only to move executions inside prison walls in reaction to the disturbing behavior of crowds and public revulsion aroused by media reports. The decision to move executions inside prison walls has usually been followed by the decline or abolition of capital punishment.

That Iran, a populous, youthful, and media-savvy nation so important to its region should remain in the moral company of its Wahhabist adversary, its blinkered Stalinist ally, and one of the poorest, most dysfunctional countries in the world, seems to contradict a law of history.

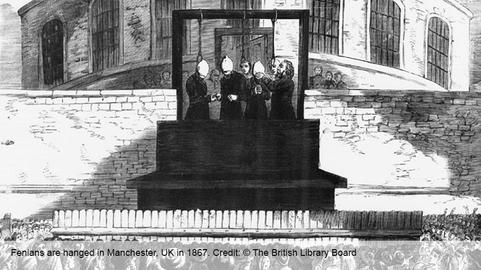

United Kingdom

Britain carried out its last public execution in 1868. Authorities hanged Michael Barett, an Irish Fenian [19th century revolutionary nationalists who fought for Irish independence] convicted of killing 12 people in a London bombing. Two thousand spectators gathered and sang patriotic songs outside Newgate Prison. Barrett’s conviction and execution troubled some observers, and a socialist newspaper speculated that historians might find that Barrett “was sacrificed to the exigencies of the police, and...the good Tory principle, that there is nothing like blood.” Britain abolished public executions the same year, with the Prisons Act of 1868, although executions by hanging continued into the 20th century.

One notable opponent of public hanging in Britain was Charles Dickens. In an 1849 letter to The Times, he wrote that though he had “no intention of discussing the abstract subject of capital punishment”, he wanted the government to make execution “a private solemnity within the prison walls”. Dickens had attended the execution of murderers Frederick and Marie Manning, and deplored the “wickedness and levity” of the large crowd that had gathered to see them hanged. “I am solemnly convinced,” he wrote, “that nothing that ingenuity could devise to be done in this city...could work such ruin as one public execution...I do not believe that any community can prosper where such a scene of horror and demoralization...is presented at the very doors of good citizens.”

The history of capital punishment in Britain is one of incremental reform followed by stages of abolition. In 1872, Britain introduced the “long drop”, a “scientific” method of hanging designed to kill the condemned quickly rather than risk strangling them slowly. In 1923, activists established the Howard League for Penal Reform and the National Council for the Abolition of the Death Penalty in response to the troubling execution of Edith Thompson, accused of being an accomplice in the murder of her husband. In 1933, the Children and Young Persons Act protected anyone who was aged under 18 at the time of their offence from the death penalty.

By the 1940s, capital punishment remained popular, but public executions held such horror in the public imagination that George Orwell reintroduced them to the dystopian London he imagined in Nineteen-Eighty-Four, in which children demand that their parents take them to hangings, and one character remarks, “I think it spoils it when they tie their feet together. I like to see them kicking.”

Britain’s last executions took place in 1964. In 1965, the Murder Act established a moratorium on capital punishment for murder, a move made permanent in 1969. It was not until 2002, however, that Britain ratified Protocol 13 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which abolished capital punishment in all cases, including during times of war. Britain now opposes the death penalty, and lists Iran as a “priority country” in its strategy to abolish capital punishment worldwide.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia beheads prisoners in public.

Amnesty International’s 2013 report on capital punishment worldwide mentions Saudi Arabia and Iran in several connections, including the extraction of “confessions” through torture and the use of capital punishment for crimes that “did not involve intentional killing”.

France

France carried out its last public execution in 1939. Authorities decapitated Eugen Weidmann, a German convicted of murder, by guillotine outside St Pierre Prison in Versailles. According to historian Paul Friedland, the French press objected to the behavior of spectators, which one paper described as “disgusting” and “unruly”, with members of the public “devouring sandwiches” and “jostling, clamoring, whistling.” Friedland argues that little of this was new, but that worldwide publicity, including the reproduction of clear photographs of the execution, caused the government to express “its regret that such spectacles, which were intended to have a ‘moralizing effect’ instead seemed to produce ‘practically the opposite results’”.

French revolutionaries adopted the guillotine in 1791 as a “humane” method of execution, and they used it to execute thousands. Long after the era of political terror, the public execution of criminals, though popular, worried thoughtful observers. Victor Hugo, a leading critic of the guillotine, wrote about “thirsting and cruel spectators” as early as 1829. In 1859, Leo Tolstoy reproached himself for being so “stupid and callous” as to attend an execution in Paris, and wrote, “if a man had been torn to pieces before my eyes it wouldn’t have been so revolting as this ingenious and elegant machine by means of which a strong, hale and hearty man was killed in an instant”.

In 1957, Albert Camus recalled in Reflections on the Guillotine that his father had once “got up in the dark”, so eager was he to see the execution in French-ruled Algiers of an “assassin” who had murdered a family: “My mother relates that he came rushing home, his face distorted...and suddenly began to vomit. He had discovered the reality hidden under the noble phrases with which it was masked. Instead of thinking of the slaughtered children, he could think of nothing but that quivering body that had just been dropped onto a board to have its head cut off.”

The French Constituent Assembly first debated abolition of the death penalty in 1791, and, though it voted to retain capital punishment, the controversy led France to adopt the “humane” device. In the late 20th century, Robert Badinter, Francois Mitterand’s justice minister, led the campaign for abolition. The last execution in France took place in 1977, and France abolished the death penalty in 1981. In 2010, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris exhibited the last intact guillotine in France. France identifies itself among “the main states committed to fighting the death penalty”, and places Iran among “the hard core of retentionist countries”.

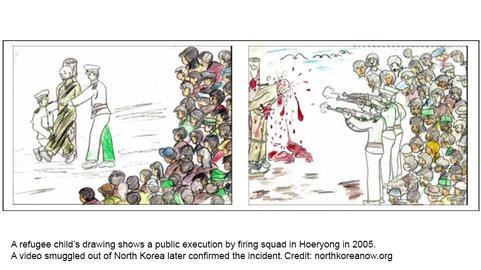

North Korea

According to a United Nations report published this month, “As a matter of state policy, [North Korean] authorities carry out executions, with or without trial, publicly or secretly, in response to political and other crimes that are often not among the most serious crimes. The policy of regularly carrying out public executions serves to instil [sic] fear in the general population. Public executions were most common in the 1990s. However, they continue to be carried out today. In late 2013, there appeared to be a spike in the number of politically motivated public executions.”

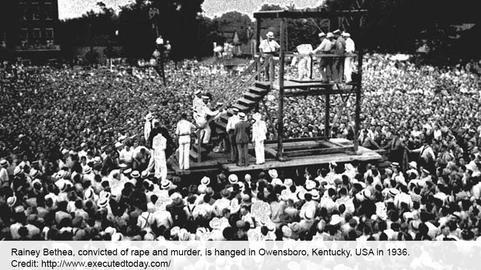

United States

The United States carried out its last public execution in 1936. Authorities hanged Rainey Bethea, who was convicted of rape and murder, in Owensboro, Kentucky. Twenty thousand people attended the execution, which journalists later denounced as a “carnival.” Media from other states noted the sale of popcorn and hot dogs at the site, and Time magazine reported that “tipsy merrymakers rollicked all night” and held “hanging parties”. Negative publicity influenced state lawmakers’ abolition of public executions in 1938.

The Death Penalty Information Center, a Washington-based non-profit organization, traces the origins of capital punishment in America, as well as the movement to abolish it, to colonial times. In the late 1700s, some American intellectuals drew influence from European Enlightenment thinkers, notably Cesare Beccaria, who had argued in a 1767 essay that no crime entitled the state to take a life. Benjamin Rush, a signatory to the Declaration of Independence, argued that capital punishment did not deter crime.

The history of the death penalty in the United States is complex, and has been determined mainly by lawmakers in individual states. Pennsylvania was the first state to end public executions, in 1834. Michigan abolished capital punishment for all crimes except treason in 1847. Wisconsin abolished it in 1853, and Maine in 1887. Six states abolished it between 1907 and 1917, but all but one brought it back by 1920. Meanwhile, scientific innovations in execution continued from the 19th century (New York first used the electric chair in 1890) into the 20th (Nevada introduced cyanide gas in 1924, and Oklahoma introduced lethal injection – which is now the most widely-used method– in 1977).

In 1972, the US Supreme Court raised constitutional objections to capital punishment as practiced and “effectively voided 40 death penalty statutes, thereby commuting the sentences of 629 death row inmates around the country and suspending the death penalty because existing statutes were no longer valid”. Many states re-wrote their death penalty statutes to address the court’s objections; Utah ended an effective moratorium when it killed a prisoner by firing squad in 1977.

In recent years, the United States has seen executions by such diverse methods as electrocution (2013, Virginia), hanging (Delaware, 1996) gas chamber (Arizona, 1999) and firing squad (Utah, 2013). But the practice is in decline, and several states have repealed capital punishment since 2007, including Maryland, Connecticut, Illinois, New Mexico, New York, and New Jersey. Human rights groups continue to press the United States to abolish the practice, as do Britain and France.

Somalia

Death Penalty Worldwide, a database associated with the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty, notes that “many executions in Somalia should be considered extrajudicial executions because they are not carried out by a functioning government...and it may be wise to view them as acts of terrorism by militias to frighten and subjugate the population in areas under militia control”.

Canada

Canada carried out its last public execution in 1869. Authorities hanged Nicholas Melady, who had been convicted of murder, outside a jail in Goderich, Ontario. According to author John Melady (a distant cousin of the condemned), Melady’s trial was controversial because of allegations that police had used a female prison informant to extract his confession. Melady was hanged several hours before the appointed time, and members of a crowd of several thousand people protested the change in schedule. Three weeks later Canada banned public executions, although later, photographs, such as the one featured on the slideshow, which was taken in 1902 in Hull, Quebec, suggest that Canadians found ways to continue viewing executions.

Correctional Service Canada notes efforts to abolish capital punishment as early as 1914, but dates the acceleration of the debate to the 1960s. The Canadian Bill of Rights, which the government enacted in 1961, changed Canada’s Criminal Code to classify murder by degree. Throughout the 1960s, existing death sentences were commuted “at an unprecedented rate”. Canada carried out its last two hangings at the Don Jail in Toronto in 1962. Protesters outside the jail denounced capital punishment as “public murder”, and authorities told the condemned that they would likely be the last people executed in Canada.

In 1966, parliament debated capital punishment, but a motion for abolition failed. In 1967, the government enacted a moratorium on capital punishment for most types of murder, and all existing death sentences for murder were commuted. A 1973 bill extended it. In 1976, the government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau introduced Bill C-84, removed capital punishment from the Criminal Code. In 1998 Canada removed references to capital punishment from its National Defence Act, which threatened death for treason or mutiny. Amnesty International has criticized Canada in recent years for not supporting the clemency appeal of a Canadian national sentenced to death in the United States.

Canada supports the abolition of capital punishment worldwide. In 2013, Canada led a resolution on human rights in Iran at the United Nations General Assembly, which its foreign affairs minister John Baird said “reinforced the expectations of Iranians looking to the new president to fulfill his commitments and address serious human rights violations”.

comments