Iran has a long history of silencing, arresting and banning student activists from continuing their studies. In addition to denying Baha’is, Iran’s largest religious minority, the right to further education, it also targets students with known political affiliation, often incarcerating and even torturing them — and it’s a situation that has developed more rapidly in the last decade.

Mehdi Aminizadeh was the first student under the Islamic Republic to become a so-called “star” student. Think more brand or label than badge of honor. In Iran, a star student is someone security agencies have singled out as “undesirable” because of his or her political activities.

From 2001 to 2005, Aminizadeh was a member of the central council of the Office for Strengthening Unity, the leading pro-democracy student organization in Iran. He was arrested four times. During his last arrest in 2003, he was tortured.

But his problems didn’t end there. In 2005, as reformist President Mohammad Khatami’s presidency drew to a close, and following entrance exams for Master’s courses across the country, the Intelligence Ministry summoned Aminizadeh. Two interrogators questioned him for two hours, asking about the activities of his organization and his views on the “Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist,” the underlying ideological principle of the Islamic Republic. “I answered in detail,” he said. “I believe that under the Iranian system it would lead to dictatorship. But not for a moment did I think that the questions had anything to do with me wanting to study for a Master’s degree.”

Aminizadeh says that at that time, relations between students, the university’s disciplinary committee and its security department appeared different than they do today. So students had no idea about the troubles that lay ahead. They knew being politically active was dangerous, but they did not know it could mean the end of their political career.

“We Could not Imagine this”

After protests at Tehran University Students’ Quarter turned violent in 1999, a number of university authorities banded together to show their displeasure. The supreme leader’s representative at the university, its head of security, the university’s vice president and the commander of the paramilitary Students Basij organization went to the campus to distribute a letter that had been written by Ayatollah Khomeini, in which he condemned the Freedom Movement political party and accused one of its student leaders of being a traitor.

Aminizadeh says he grabbed the copies of the letter out of the hands of those distributing them and tore them up. When the group of regime officials issued a complaint against him to the disciplinary committee, he refused to appear before it. “After my arrest,” he said, “one of the officials climbed the podium and as a response to my act, tore up the publication I was in charge of. This was the most one could expect.” He said there was no way the situation then would have led them to worry about their future education, and certainly not to imagine that they would be put on some sort of list. “At that time they could not create problems for us at the university. We could not even imagine such a thing.”

But by 2005, the situation had changed. After the results of the entrance exams were published, Aminizadeh discovered he had been accepted on a Master’s degree course in political science. But when he arrived to register, he was given a piece of paper with a star next to his name. “Your case is incomplete and you must go to the Educational Testing Organization,” he was told.

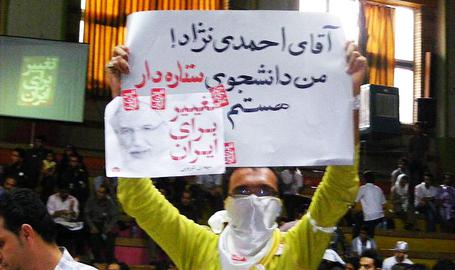

When he arrived at the office, he was told that the Intelligence Ministry had opposed his plans to register. For a few months afterward, he went to the department several times, and even met with former president Mohammad Khatami and Mehdi Karroubi — the future reformist presidential candidate who until 2004 was the speaker of Iran’s parliament. He wrote an open letter to the new president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, but it led nowhere. The term “star student” began to appear in the media, referring to students who had been banned from continuing their education.

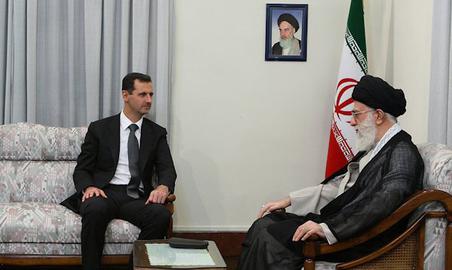

Aminizadeh believes that Karroubi was instrumental in making the media pay attention to the growing issue of “star students”. In 2006, he said, a student called Peyman Aref was also classified in the same way. “Now there were two of us,” Aminizadeh said. “The next year, the number of star students started to grow rapidly. We staged protest rallies and eventually went to visit Mehdi Karroubi, accompanied by a reporter from the newspaper Etemad-e Melli. Karroubi strongly defended us. The day after the visit, the main headline of the newspaper was about us. In another meeting with the authorities, we heard that Ayatollah Khamenei himself was personally involved.”

But at the time, Mohammad Mehdi Zahedi, the Minister of Science under Ahmadinejad, denied the existence of star students. The Committee to Defend the Right of Students to Education was formed in response to these denials from the authorities.

Repeat Performance

Little by little, Aminizadeh began to lose hope that he would be able to continue his education, and so he accepted a contract job outside Tehran. In 2008, he finally accepted the fact that he could not return to Tehran University, and he decided to give Azad Islamic University a try. He was accepted, but again, when he went to register, he was told that the Intelligence Ministry was opposed to it. “There were 20 of us,” he said. “We met with the head of security and his people. They defended the decision.” He said authorities told him there had to be some way of selecting students. Otherwise, they said, “a rapist could get into university, and then who would defend your mother and sisters?” He said this resistance continued throughout a semester. “We got nowhere until we appealed to Mehdi Hashemi [son of former president Hashemi Rafsanjani], who at the time was a member of Azad University’s Board of Trustees.”

Mehdi Hashemi immediately called Hashemi Rafsanjani and got his permission to talk to the university’s security department. “He said they had to register the kids right away,” Hashemi told them. With that, Aminizadeh and a group of other star students were able to continue their education at Azad University.

The Lock That Makes No Sound

Being banned from education can turn lives upside down, especially when people have plans hinging on further education. “It is one of the worst kinds of repression,” Aminizadeh told me. “Prisoners suffer imprisonment for the sake of their ideals, but being banned from education feels like being locked up without hearing the click of the lock. They build a ceiling over your head and you cannot climb any higher. And they do it in a way that nobody gets wind of it. And you yourself cannot even believe it for some time. Some people told me: ‘It’s nothing! It’s actually better that you were rejected.’”

But the feelings of anger and helplessness that follow are real. “From 1997 to 2005, more than 85 percent of my time was spent worrying about it,” Aminzadeh said. “My personal life was overshadowed by it. After being banned, you unconsciously start to compare yourself with other students, students who are enjoying what life has to offer — who studied, went to parties, had relationships with girls, and got important jobs after graduation. We had dedicated our lives to bring about change but we had failed, while they had no worries.”

In all, Aminizadeh was arrested four times. The last time, in 2003, he spent three months in jail, was beaten and was subjected to sleep deprivation.

In the aftermath of the disputed 2009 presidential election, authorities once again summoned Iran’s first “star student,” even though he had not been politically active for a long time. At the time, his wife, daughter of a prisoner of conscience, was pregnant. He decided enough was enough. He did not want their child to grow up under the same conditions. They crossed into Turkey on foot and left Iran behind. “I would still love to return to university,” he said, adding that political science would still be his first choice. “Right now I am studying civil engineering, but I would love to go back to university after I am established.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments