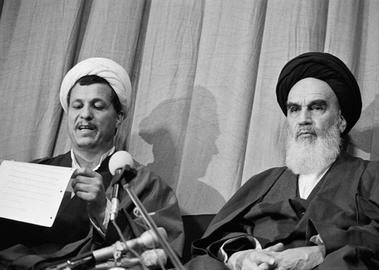

In the early days of the Iranian Revolution, the late Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani – who died on January 8 – was but one of many Islamic clerics surrounding the shah’s main adversary, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Gary Sick, who served on the US National Security Council during the revolution, and was President Jimmy Carter’s principal White House aide for Iran, had not heard of him at the time.

“The first time I heard Rafsanjani's name was as one of the people in the Revolutionary Council around Khomeini after he came back to Iran from exile in February 1979,” Sick says. “That speaks a great deal to the US intelligence during that period, which was really not very good, frankly. They didn't really know what was going on.”

Rafsanjani’s influence as a leading member of Khomeini’s circle became obvious to Americans during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, which began when Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Iran.

“That was the period when he rose very quickly in importance, when he became a very key figure in policy making,” Sick says. “He emerged as the commander in chief of the military under Khomeini. He was the guy who was actually running the war.”

That war was to become the defining trauma of the Iranian Revolution, providing the new Islamic Republic with its official heroes and villains, alliances and enmities, and a new set of resentments against the United States, which had worked to isolate it ever since pro-Khomeini students had taken US diplomats hostage in November 1979.

Along with Khomeini, Rafsanjani was the public face of Iran’s victories and defeats. “He had a role to play in what I regard as the biggest mistake that Iran ever made,” Sick says. “That was their decision in 1982 after they had pushed Iraq back to Iran’s original borders – and they had an opportunity to sue for peace at that point and they would have emerged as the winners in that war – to keep on fighting. That was a terrible strategic error.”

Instead of returning to the status quo, many of Iran’s revolutionaries dreamed of marching to the Shia holy city of Karbala, and of overthrowing Saddam Hussein. But in the end, it was also Rafsanjani who convinced Khomeini to stop the fighting.

“I give him great credit for persuading Khomeini to end the war,” Sick says. “Khomeini had said that they were going to fight until death. But things were not going their way. Rafsanjani had a major role to play with Iran’s acceptance of UN Resolution 598 in August 1988, when Iran accepted a ceasefire.”

From Iran-Contra to the Presidency

Sick remained on the National Security Council for just a few weeks under President Ronald Reagan, whose administration would, years later, become embroiled in the major scandal known as the Iran-Contra affair.

The scandal involved secretive US efforts to open channels of communication with the Islamic Republic by illegally selling it arms – in some cases through Israel – in exchange for Iranian efforts to free American hostages held by Iranian-backed groups in Lebanon.

Reagan administration officials then used profits from the arms sales to fund anti-communist militants in Nicaragua known as the Contras.

Rafsanjani was to prove a willing interlocutor with the Americans throughout the project and seemed at times to be waiting for Khomeini’s death so that he could build relations further.

In February 1989, Rafsanjani became president of Iran. That June, Khomeini died. Rafsanjani helped his then-friend and fellow revolutionary, Ali Khamenei, become Khomeini’s successor as supreme leader.

Rafsanjani, as one of the architects of the post-Khomeini order, made himself the face of Iran’s post-war reconstruction and alliance making.

“From the time Rafsanjani came into office as president, he was a figure who clearly was extremely pragmatic,” Sick says. “He was open to alternative ways of thinking about policy, and he was very willing to work with other parties, including the United States — probably more willing than almost any other major politician in Iran.”

In the US, the administration of President George H.W. Bush, which also began in 1989, continued negotiations with Iran for hostages held by Iran’s allies in Lebanon. Rafsanjani, Sick says, was believed to have been involved through intermediaries.

“Bush's famous statement that ‘good will begets good will’ was directed at Rafsanjani,” Sick says. “The Americans promised that if the Iranians got the hostages out, the Americans would cooperate with Rafsanjani more closely than they had in the past and that they would begin to end the hostility between the two countries.”

But the rapprochement ran aground. “Rafsanjani kept his promise. He actually got the hostages out. But it came just as George H.W. Bush was engaged in another election campaign. He couldn't keep his promise, and he was defeated in that election. And the Clinton administration wasn't the least bit interested in pursuing it. That was probably one of the greatest disappointments of Rafsanjani's political life.”

The Ugly Interlocutor

During his presidency from 1989 to 1997, Rafsanjani set the tone for one of Iran’s most peculiar institutions, a presidency wherein a pre-vetted but directly elected president would operate in collaboaration with a powerful supreme leader — Ali Khamenei.

“Rafsanjani was personally responsible for creating the presidency as it now exists,” Sick says. “After Khomeini died, he set up the system, so that the president would have a major, powerful role. And in the process of doing that, he made himself the first president.”

Rafsanjani used the office as a platform for his main project, Iran’s post-war reconstruction. But the role was not ideal for him. “His legacy is going to be very mixed because, although he wanted very much to rebuild Iran, he couldn't get away from the fact that Iran was a revolutionary power, and he was unwilling to relinquish that position as a revolutionary to really focus on economics.”

And there was no question he was a ruthless revolutionary, willing to crush dissent at home and to attack perceived enemies abroad.

In 1997, a German court found Rafsanjani, Khamenei, and other Iranian officials responsible for the murder of four Kurdish dissidents in Berlin. In 2006, Argentinian authorities issued an Interpol arrest warrant for Rafsanjani and several other Iranian officials believed to have been involved in the 1994 bombing of a Buenos Aires Jewish community center that killed 85 people.

“He was a major figure and he can't avoid responsibility for some of the things that were done,” Sick says of Rafsanjani’s main era of political power, through various offices, from 1979 to 2009. “He had a good deal of influence with the security services; he knew what was going on in Iran's foreign affairs. I don't think he always approved of it, and there have always been internal fights within the Iranian government. But it's impossible to extricate him from the history of Iran during that period. And a lot of that is very ugly.”

From Revolutionary to Kingmaker

His time as president aside, Rafsanjani preferred more peripheral offices, from which he could wield more subtle influence. “The one thing that has always struck me about Rafsanjani's leadership,” Sick says, “was that he was never one to get out and lead the troops, lead everybody off in a very clear direction. He was not prepared to commit himself, and to say, ‘This is the policy that I stand for and could lead everybody on,’ and to take whatever slings and arrows might come at him because of that.”

During Iran’s 2009 presidential elections, Rafsanjani supported opposition candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi against the incumbent, the conservative populist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

And when Mousavi and another opposition candidate, Mehdi Karroubi, contested the election with the help of millions of opposition supporters calling themselves the “Green Movement,” Rafsanjani supported them, too. But only up to a point. When security forces cracked down on protesters that year, and eventually put Mousavi and Karroubi under house arrest in 2011, Rafsanjani stayed cautious enough to avoid complete political eclipse.

During the 2013 presidential elections, Rafsanjani backed Hassan Rouhani, a nominal moderate with deep roots in Iran’s security state. Rouhani promised a pragmatic, Rafsanjani-like project to resolve Iran’s standoff with the West over its nuclear program and improve the economy. He won, and Rafsanjani remained a godfather figure to an increasingly cautious and conservative reform movement.

Iran Without Rafsanjani

Now that Rafsanjani is gone, many Iranians wonder what will happen to their country’s fragile prospects for reform and diplomacy. Absent the elder revolutionary who once dealt with the US in the shadows, many wonder who will keep Iran from falling back into the isolation preferred by the country’s most hardline revolutionaries. But Sick thinks Rafsanjani was very nearly a spent force.

“I don't think there's much difference, frankly,” he says. “Since about 2009, Rafsanjani's immediate role in policy making has been quite limited. His position had weakened substantially. He had put a lot of effort into opposing Ahmadinejad and he lost. He was a waning force.”

Rouhani’s supporters nevertheless worry that their candidate has lost his most established patron. “Rouhani will miss him,” Sick says, “but I don't think Rouhani is going to fall or rise on the basis of Rafsanjani alone.” And Iran’s reformists, he says, come in many categories. “The reformists are an element in the making. The people who supported the Green Movement are relatively quiet now. Many of them supported Rouhani simply because he was the lesser of evils in the last election. I suspect that they will continue to support him since their own leaders — Mousavi and Karroubi — are under house arrest. They have to look where they can for any leadership. But they were not looking to Rafsanjani.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments