On the morning of January 19, journalist Shahrzad Elghanayan saw an email on her phone from a CNN editor, asking her to write a story about the catastrophic collapse of Iran’s oldest high-rise, the 17-story Plasco Building in Tehran.

“I was horrified and shocked just like everyone else,” says Elghanayan, who lives in New York. “I immediately went to my computer and saw the videos, and saw the fire and the building collapse. As soon as it collapsed, I was thinking about the people inside.”

The editor knew Elghanayan had a family connection to the building because of op-eds she had written about her grandfather, Habib Elghanian, the Jewish industrialist and philanthropist who had built the tower in 1962.

Elghanian was executed on May 9, 1979, during the early days of Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Revolution. His killing shocked Iran’s Jews and was one of the reasons tens of thousands of Jews fled Iran in the ensuing years.

Although she didn’t have any memories of the building itself — her family left Iran in 1977 when she was only five — Elghanayan says the building held special significance for her family.

“The fact that this building stood there meant that there was a legacy, a symbol that was still there,” she says.

The Family Business

Habib Elghanian was one of Iran’s most famous industrialists and a member of an ancient Jewish community that dates back to 586 B.C. In the years before the revolution, there were between 80,000 and 100, 000 Jews in Iran.

Born in 1912, Elghanian was one of eight siblings, seven brothers and one sister. With his brothers, he launched Elga LLC in 1936, a company that imported goods from the US and Switzerland.

In 1948, the brothers expanded into the plastics industry, founding Plascokar, the company after which the Plasco tower would later be named.

While Elghanian’s granddaughter has not been able to find many records related to the building, she does know that Norollah Elghanian, one of Habib’s brothers who was based in New York, first suggested the idea of a Tehran high-rise.

Norollah, she says, worked on construction projects in New York, and wanted to build a high-rise with an indoor mall and office space in Iran.

Of the seven brothers, Habib was the most attached to Iran and preferred to spend most of his time there. Of all the brothers, he was also the most famous in Iran and was recognized as a leader of the Jewish community.

He felt a strong attachment to Iran’s Jewish heritage. “He felt that the Jews in Iran had survived such a long time in Iran, and so it was important for him to keep the traditions,” Elghanayan says. “But he also felt very, very Iranian. He could have gone anywhere, but he decided to stay in Iran.”

Family, too, was important to him. While her own father, Karmel, grew up in the US, Elghanayan remembers him telling her about time he spent working with her grandfather in Tehran after he finished university.

“My father told me that his father taught him a lot about the business,” she says, referring to the running of Plasco’s retail stores in the city. “My grandfather would pick him up sometimes, and they would go and have lunch at home. Those were very special times for him.”

And when the Plasco Building was erected in 1962, it became one of the special places in Tehran and a symbol of the city’s development. “Everybody liked to go there,” Elghanayan says. “And it had significance for the Jews, obviously, because they were proud.”

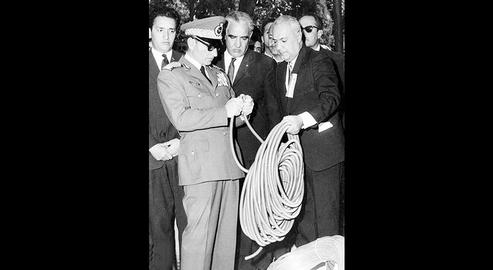

Elghanian presents the shah of Iran with a plastic hose made in one of his factories.

Bitter Envy

Not everyone in Iran approved of the Plasco Building. Once it was constructed, Elghanian became the target of religious prejudice from some of the Iran’s most influential Islamic clerics.

In 1962, shortly after the Plasco Building was constructed, Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleghani complained that what was then the tallest building in the country had been built by a Jew rather than by Muslims.

In those years, Iran maintained diplomatic relations with Israel, and engaged in economic and military cooperation.

Elghanian himself worked on business and philanthropic projects in the country. He developed the 22-story Shimshon tower, part of the Diamond Exchange district in Ramat Gan, which was finished in 1968.

He also contributed to the establishment of a kindergarten and a hospital wing, and bought former Prime Minister Ahmad Ghavam’s house in Tehran and gave it to Israel for use as an Israeli diplomatic mission.

Aryeh Levin, an Israeli diplomat and Iran specialist who was born in Tehran in 1930, and who served with Israel’s diplomatic mission to Iran in the early 1970s, knew Elghanian in the 1960s.

“He was an astute and powerful businessman who had built an empire,” Levin says. “I thought he was highly representative of the emerging Jewish community during the Pahlavi era, rising from the shut-in and persecuted minority that had existed before.”

“Relations between Israel and Iran were positive,” he says. “Habib and his brothers were willing mainly to contribute to hospitals and other public welfare organizations but did not undertake business on a large scale.”

Yet while Iran and Israel could do business, he says, officials were aware that the relationship was sensitive in Iran. “The shah did not want to publicize this connection, even if there were intimate components of military and strategic understanding, much of it against Egyptian and some other Arab activity.”

Relations darkened somewhat following the 1973 war between Israel and Egypt.

“The shah was very much taken by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and critical of Israel. There was also incitement and tension in the streets against Israel. However, the government took pains to assure us that there was not to be a rupture. Relations with Israel held steady until the departure of the shah and the coming of Khomeini.”

“A Foe of God’s Friends”

Shahrzad Elghanayan’s family moved back to the US, where her father had grown up, in 1977. In November 1978, Habib Elghanian traveled to New York on a family visit. This was the last time she saw her grandfather.

By then, Iran was in a revolutionary situation as demonstrations mounted following the mass shooting of protesters by the shah’s forces that September. The family, she says, did not want him to return at such a dangerous time.

“Everybody begged him not to go back,” she says. “They advised him to just wait until the dust settles because nobody knew what was going to happen. He wouldn’t have any of it. He wanted to go back to his work and his home.”

His eldest son was still in Iran, and he also felt a responsibility toward the Jewish community. “He said that if anybody is in danger, I’m not going to just hide here and let something happen to them. If the situation is dangerous, I am going to be there with my people.”

On March 15, 1979, just over a month after the victory of the Iranian Revolution, Elghanian was arrested at another of the family’s commercial properties, the Aluminum Building in Tehran.

He was taken to Qasr Prison but was not allowed to see family members or a lawyer. His family could exchange notes with him though prison staff, but otherwise received no news of him.

On May 8, he was subjected to a 20-minute show trial, in which he was accused of a host of crimes including "association with the shah’s regime,” being a “Zionist Spy” and “a friend of God's foes and a foe of God's friends.”

In the court, Elghanian asked for mercy and distanced himself from the shah and Israel. At the time, physical torture was commonly practiced in Iranian prisons, and hundreds of prisoners were forced to confess against themselves.

Elghanayan says that she doesn’t have any information about what happened to her grandfather in prison, but agrees that torture could have played a part in his plea for mercy.

The following day, he was shot to death by a firing squad. A photograph of his bloody body was published in Iranian newspapers.

Many Iranian Jews took the killing as their cue to flee Iran. Elghanian’s eldest son, Fereydoun, along with his family, was among them.

Elghanian’s execution made headlines in Israel as well. “Khomeini's motives were, it seems, a decision to ‘show his hand’ and impress the populace,” Levin says. Elghanian was a symbol of Jewish success and was made an example of economic advantage-taking.”

While non-Jewish merchants were also attacked during the revolution, he says, Elghanian’s killing was significant because of its racial subtext.

“Public reaction in Israel was strong but did not persist for long,” Levin says, “since the revolution itself was a world-class event that lasted for a long time. There were many attempts to save Elghanian's life. Some reached Khomeini himself, but made little impression on him.”

Soon, all that was left of the Elghanian family in Iran was their buildings, which testified to a political order more tolerant of religious minorities.

In her CNN article, Shahrzad Elghanayan wrote about how the revolutionary groups that took over the building neglected it and allowed it to become increasingly unsafe.

Authorities in the Islamic Republic, she wrote, “always loathed the landmark that was built by my family.”

The collapse of the Plasco Building became the latest episode in a painful national chronicle, as well as a painful family story.

“That building was a piece of our family’s history,” Elghanayan says. “It is gone because they didn’t take care of it.”

Shahrzad Elghanayan is now writing a biography of her grandfather.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments