What’s it like to live on the margins of a metropolis in Iran today? Those who do are confronted with some of the most serious crises facing the country today, with social, economic, political and security repercussions. Various groups and organizations have reported on and collected data about the predicaments of margin-dwelling in Iran but, despite the significance of the subject, the reliable statistics needed for in-depth political, social and economic analyses, either do not exist or have not been made public.

This is the first in a series of reports on living on the margins in Iran. With the series, IranWire will aim to use available statistics and data, as incomprehensive of some of it might be, to arrive at a more accurate picture of the phenomenon of living on the margins in Iran and the crises emerging from it.

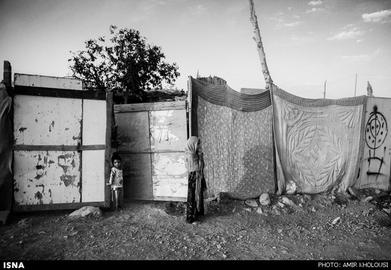

“A street in the heart of the shantytown, a street in a town of poverty and decay. A street that is narrower than an alleyway and smaller than a backyard. The life of this street and others in the shantytown are at the mercy of the wind. A strong wind could topple the shacks and then nothing would remain of the alley, of the street and of the backyards of slum-dwellers. Everything is growing from the heaps of garbage, but garbage kills hygiene. They wash things, they cook and they eat in a teeny-weeny space. They wash their teacups with mud. Children taste bits of food left by others ... Tehran shantytowns are the product of the growth of dependent capitalism following the 1963 American reforms [the shah’s “White Revolution”]. Addiction is rampant in the shantytowns and even many small children are addicts...”

The above is from a report published by the daily newspaper Kayhan on March 27, 1980, [Persian link] shortly after the Islamic Revolution. It marked a visit by Abolhasan Banisadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic, to a shantytown east of Tehran.

But in the 38 years since that report, the plight of Tehran’s slum dwellers has not eased — although the difference is that, at the time, people blamed the shah’s “dependent capitalism” for the shantytowns, whereas today the blame is likely to fall on the mismanagement and bad policies of the Islamic Republic over the last four decades.

Before the Islamic Revolution

Life on the margins is a feature of modern Iran as much as urban living is, and has been a phenomenon since the birth of the modern Iranian city.

According to the first-ever census of Tehran, conducted more than 150 years ago in 1867 during the reign of the Qajar king Nasseredin Shah (who reigned from 1848 to 1896), more than 10 percent of the population of the Iranian capital — around 17,000 —lived outside city gates [Persian PDF]. The first shacks inside the capital started appearing in 1922 but it was only from the 1960s on that shantytowns turned into a serious feature of Tehran’s landscape.

“Tehran Is Iran’s Capital” [video], a documentary made by the Iranian movie director and documentary filmmaker Kamran Shirdel in 1966, is a poignant and painful narrative of the wretched life of Tehran’s margin-dwellers. Even 50 years on, it brings out an emotional response.

Before the Islamic Revolution, margin-dwelling was a result of migration from rural to urban areas and the changing social and economic structures of the country. Studies show that in the 1970s, 91 percent of margin-dwellers were migrants who had come from the countryside to live in cities. By 1980, there were more than 4,500 shanties in Tehran, host to more than 10,450 households.

Revolution and War with Iraq

The explosion of margin-dwelling was precipitated by first the 1979 revolution and then the 1980-1988 war.

In revolutionary propaganda, the term “margin-dwelling” actually had positive connotations. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the revolution, praised slum dwellers as strong and upright people who were superior to those who lived in palaces. Early after the revolution, poverty and living in slums was considered a badge of honor and this, in turn, encouraged more migration from rural Iran to urban areas.

But the affairs of the state were now in the hands of people who were neither experienced nor knowledgeable about the issues of urbanization. Only a few months after the revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini ordered the creation of the Housing Foundation of the Islamic Republic [Persian link], to be led by Hadi Khosroshahi, who believed he had the perfect recipe for solving the housing crisis and announced: “Before this winter, all the oppressed must be homeowners.”

It has been almost 40 years since that winter and the legacy of that high-flying rhetoric has been nothing but an explosive increase in the population of “the oppressed” and the influx of hundreds of thousands of unfortunate villagers who were drawn to the margins of the cities in the vain hope that they would prosper. Add to this the people who were displaced by the eight years of the Iran-Iraq war [Persian link] and had no choice but to leave their homes in western Iran and seek shelter in Tehran and other cities away from the war zone.

The 1996 census, conducted eight years after the war, found that one-fifth of Tehran’s population lived in shantytowns and shabby housing.

After the War

The end of the war was the beginning of a new phase of margin-dwelling in Iran. Although the Iranian politicians of the 1990s had personally witnessed the consequences of high-handed changes to the structure of the Iranian society in the 1950s and the 1960s under the shah, they ignored the lessons of history and decided to open up the closed economy of Iran in the manner that they saw fit.

Extensive privatization started under the presidency of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997) who liked to call his administration the “Government of Reconstruction.” Some of the disastrous consequences of the way privatization was implemented took time to unfold, but the 50 percent inflation had an almost immediate impact [Persian link]. Inflation, of course, affected everybody but it made life in villages and small towns especially hard — so much so that the migrants could justify living in wretched conditions on the margins of big cities.

But the hard lives of migrants was not the only consequence of this influx from rural to urban areas. The first tremors of a growing discontent after the 1979 revolution made themselves felt in the 1990s on the margins of megacities. In 1992, for instance, bloody riots broke out in the holy city of Mashhad [Persian link]. The rioters occupied a number of police stations, several banks, the municipality building and other government offices. The riots were put down after only two days. Several people were killed, hundreds were rounded up and four of the rioters were hanged.

Ahmadinejad and After

A new round of margin-dwelling started in the 2000s. On the one hand, Iranian politics witnessed significant changes and, on the other hand, the first signs of climate change and environmental crisis appeared. If earlier the growth of margin-dwelling was caused by social, economic and political factors, now climate change was added to these factors.

Climate change started forcing villagers, left with no other options, to leave everything behind and seek refuge in the margins of the cities. Thousands more Iranian villages were emptied out and since big cities were filled to capacity, it was now the turn of smaller cities and towns to shelter the migrants. For big cities like Tehran, Mashhad and Tabriz, margin-dwelling was not something new, but in the last 10 years small towns like Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman — where 63 percent of the population live on the margins — have held the record for new margin-dwelling [Persian link].

And, besides everything else, beginning in 2009, Iran’s economy started a steep descent. Following on from the ill-conceived project by Hadi Khosroshahi early after the revolution, Ahmadinejad’s Mehr Housing project became the second official campaign that in practice promoted further margin-dwelling. It proved to be one of the most destructive government interventions in the history of housing in Iran [Persian link]. Whereas before the Mehr Housing project people used to build their own shacks in the desolate outskirts of the cities, now it was the government that, on their behalf, took over the job. And the result was a costly disaster.

Side by side with environmental degradation and disastrous government policies, sanctions and the ever-present threat of war made the situation even worse.

On the Verge of the Future

A new century in the Iranian calendar, the 14th century, will start on the first day of spring 2021. And yet Iran is looking to a future filled with crises of every kind. One such crisis is the scope of margin-dwelling and the worn-out and inefficient fabric of the cities. According to a 2014 study by the Iranian Parliament Research Center [Persian link], the area of worn-out urban land in Iran is more than 76,000 hectares. But the area of inefficient urban fabric is even bigger, covering around 141,000 hectares. According to Houshang Ashayeri, Deputy Minister of Roads and Urban Development, around 20 million, or one-fourth of Iranians, live in such areas [Persian link].

This means that, besides all other environmental and non-environmental threats and crises, one Iranian in four lives in a miserable shelter in an equally miserable environment.

Read the full Living on the Margins in Iran series:

Living on the Margins in Iran: An Introduction

Living on the Margins in Iran: Razavi Khorasan

Living on the Margins in Iran: Mashhad and the Cities of Razavi Khorasan

Living on the Margins in Iran: East Azerbaijan

Living on the Margins in Iran: Bandar Abbas and Hormozgan Province

Living on the Margins in Iran: Chabahar and the Province of Sistan and Baluchistan

Living on the Margins in Iran: The Rise and Fall of Khuzestan

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments