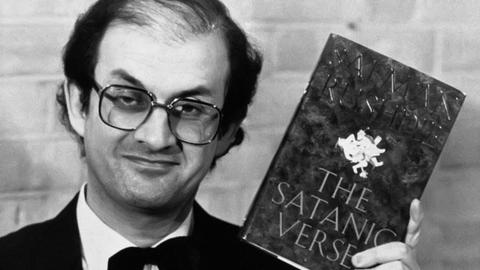

A former official who wrote an influential book defending Ayatollah Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa against the British writer Salman Rushdie lives in London. In his 1989 book A Critique of the Satanic Verses Conspiracy, Ataollah Mohajerani, the former Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance of Iran, justified the proposed assassination of the British author based on the teachings of the Koran and the teachings of the Prophet Mohammad. The fatwa led to years of diplomatic isolation for Iran and confirmed its status as an international pariah. Mohajerani has been living in the United Kingdom since he was forced into exile, allegedly because of an illegal affair, in 2004. It is not clear whether he has become a British citizen or holds an “indefinite leave to remain” visa. Mohajerani, who refused to be interviewed for this article, has never expressed any regret for writing the book and has not commented about the current status of Khomeini’s fatwa against Rushdie.

“There is no question that what he [Mohajerani] has written is nothing short of incitement to murder,” Kaveh Moussavi, a human rights lawyer at Oxford, told IranWire. “His explicit exhortation to the faithful to commit murder is crystal clear in the book. He does not pull his punches and repeatedly states that it is the duty of all Muslims to murder Rushdie.”

Moussavi, who was a judge at the Hague’s International Criminal Court, adds that the “crime was not committed in the UK” and that incitement to murder “is, sadly, not as yet a universal crime and not subject to universal jurisdiction and as such can’t be prosecuted here in the UK.”

If Mohajerani continues his incitement, however, a case could be opened, Moussavi said.

Iran has not only never withdrawn its fatwa on Rushdie, it has repeatedly defended it. Ayatollah Khomeini had said that Muslims can also pay others to kill Rushdie. Taking this as its cue, a wealthy Iranian institution, the 15th Khordad Foundation, has posted a prize of $3.3 million to anybody who kills the British writer. The head of the institution Hasan Sanei is appointed by the Supreme Leader. Sanei has repeatedly maintained that the prize money is still available.

An Erudite Functionary

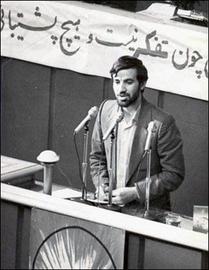

Mohajerani was an ultimate regime insider. As a 25-year old revolutionary student, he organized protests at the University of Shiraz in central Iran in the months preceding the February 1979 Revolution. After the revolution Mohajerani wrote for a publication called Valfajr (the Victory), in which he visciously attacked Mehdi Bazargan, the provisional prime minister who resigned after Ayatollah Khomeini endorsed taking American diplomats hostage.

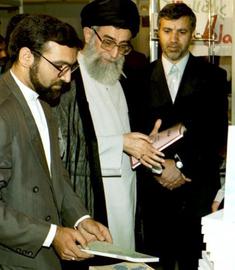

Mohajerani was a member of parliament from 1980 to 1984, and then served as parliamentary liaison for Prime Minister Mir Hossein Moussavi and President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. In 1997, Mohajerani was appointed as Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance for the government of the pro-reform president Mohammad Khatami.

Mohajerani was never a run-of-the mill regime functionary. He completed a PhD in history at Tehran University, wrote several books about history and literature and had a popular column in one of Iran’s largest newspapers, Etela’at (“Information”). During Mohajerani’s three-year tenure as the Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance, the reformist press flourished and many banned writers, filmmakers and artists started to work again.

Like many other revolutionaries of his generation, Mohajerani adopted a different politics in later life. In a speech during a commemoration for the former provisional prime minister Bazargan in 2001, Mohajerani said: “Bazargan was ahead of his time and was misunderstood by his contemporaries.” But Mohajerani never apologized for the actions against the elderly politician that lead to Bazargan’s resignation, or for the oppression unleashed on Bazargan’s colleagues who languished in prison for years or were executed.

A Critique of the Satanic Verses Conspiracy is among the darkest chapters of Mohajerani’s resume. The book was dedicated to Ayatollah Khomeini and defended a “clash of civilizations” narrative according to which the West had knowingly published Rushdie’s book to fight against Islam, and justified the fatwa on Islamic grounds.

A 250-Page Treatise Supporting Murder

Mohajerani’s life has an uncanny parallel with that of Rushdie. He lives in Harrow, not far from The Bishops Avenue, where Rushdie spent years in hiding in the violent aftermath of Khomeini’s fatwa. Mohajerani started his reign as Minister for Culture and Islamic Guidance just when the British author was finally able to leave his hiding place. And during his hiding years, Rushdie had written his majestic novel The Moor’s Last Sigh, loosely based on the character of Boabdil, the last Moorish king of southern Spain’s Islamic emirate in Granada, who spends his life dreaming about his lost empire and whose physical body ages twice as fast as a normal person. Add that to the moor’s complicated relationship to the women in his life and it’s easy to see something of a poetic parallel not only with Rushdie, but with Mohajerani. In 2004 Mohajerani was imprisoned, then released on bail, due to a suit brought about by a woman who alleged Mohajerani had lied to him about turning their sigheh, or “temporary marriage,” into a permanent one.

Support for Rushdie’s murder wasn’t a passing act of youthful ignorance. When appointed as culture minister in 1997, Mohajerani proudly said that he had quickly decided to write a book about Rushdie after Khomeini’s ominous fatwa was issued in February 1989. He went on to tell the story of how he had written the 250-page book in 40 days, during which he only slept 30 minutes a day. Even after his dismissal and eventual departure to the UK, the ex-culture minister seemed to keep up his obsession with Rushdie. When Rushdie was knighted in 2007, Mohajerani wrote an article to criticize the Tony Blair government for the move and called the UK “a strange land with a government that acts strange.”

“There is no doubt that Blair knew well that this decision will lead to Muslim reaction,” Mohajerani said, pointing to the Pakistani parliament’s condemnation of the decision and a speech by Ijaz-ul-Haq, then minister for religious affairs in Pervez Musharraf’s government. “How can Rushdie be considered a servant to literature due to the nastiest slurs he has spoken against Prophet Mohammad, Abraham and Prophet Mohammad’s wives?” Mohajerani wrote. In 2010, in an interview with Al Arabiya, he did claim that he opposed to “killing a writer because of his writings,” but he has continued to defend his book on Rushdie.

Mohajerani’s Defense

Mohajerani’s book is unequivocal in its support for Khomeini’s fatwa. The author notes that Muslims in cities ranging from the UK’s Bradford to Pakistan’s Islamabad had demonstrated against The Satanic Verses before Khomeini issued the fatwa. For him, the six demonstrators who died in Islamabad after clashing with police during their raid on a US mission were “martyrs,” and he wrote: “The blood of Indian and Pakistani youth was shed to show the Muslim zeal and will.”

Mohajerani refutes those analysts who said Khomeini’s fatwa, which came after his humiliating withdrawal from the eight-year war with Iraq, was for domestic political purposes, and insists on its compatibility with religious law. This was while many Muslim commentators, including those of Egypt's influential al-Azhar mosque, had claimed Khomeini’s fatwa to be without foundation since Islam does not permit the killing of people without a proper trial.

Mohajerani begged to differ.

“Salman Rushdie has openly confessed to being a kaffir [unbeliever] in The Jaguar Smile [Rushdie’s first non-fiction book, a travelogue of a journey to Nicaragua] and he has insulted the beliefs of the Muslims and the Prophet Mohammad... He was born in a Muslim family and is thus a fetri morted [a Muslim who willingly leaves his religion] and the punishment for such a person, especially after insulting the Prophet Mohammad, is execution,” Mohajerani wrote.

Mohajerani also cited the example of Kaab bin Ashraf, a Jewish merchant of seventh-century Arabia “who had written romantic and sexual poetry” about Mohammad’s wives and was murdered by Muslims with the permission of their prophet.

He then goes on to claim that not only would all Islamic schools permit such a fatwa but that a similar attitude is also found in the Bible and in Avesta, the holy book of Zoroastrianism, Iran’s ancient religion. He goes on to extend his claim by telling a story of his visit to Lenin’s museum in the Soviet Union in 1983. When seeing that some students cried when faced with Lenin’s belongings, Mohajerani said he realized that “even if someone is a Marxist and has accepted the materialist logic, they’d still safeguard the Lenin body and consider it sacred.” All people will defend what is sacred to them, he concluded.

In the closing pages of the book, Mohajerani ominously predicts Rushdie’s demise. “When a writer uses the ugliest imagination and words to attack the most sacred values, is there any doubt that in this fight of darkness with dawn, the darkness will perish?” Mohajerani wrote. “Rushdie represents such an action; Khomeini’s fatwa will ring eternally. Rushdie might be alive on the surface but he is a prisoner of his dark imagination and his lust and will taste death at every moment of his life. The fatwa of Khomeini has imprisoned him in the fortress of the West.”

Toward the end of the book he quotes the Old Testament’s Book of Job: “Terrors take hold on him as waters, a tempest stealeth him away in the night/The east wind carrieth him away, and he departeth: and as a storm hurleth him out of his place./For God shall cast upon him, and not spare: he would fain flee out of his hand./Men shall clap their hands at him, and shall hiss him out of his place.” And then the book’s final sentence: “The idiot who talked too much shall perish,” a somewhat free translation of a quotation from the Old Testament’s Book of Proverbs.

Life in London, UK

That a man who wrote a book inciting the murder of a British citizen has come to call London his home will seem outrageous to many. That he is also known as a liberal commentator, even more so.

After Mohajerani resigned from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance in 2001, Khatami appointed him as head of the International Center for Dialogue Among Civilizations, which advocated for the concept of “dialogue” that the reformist president had popularized internationally during a speech at the United Nations. The appointment seems ironic since Mohajerani’s book on The Satanic Verses and his 2003 book Islam and the West are a staunch defense of the narrative of “clash of civilizations.”

But this is, perhaps, less surprising when we remember Khatami himself openly defended capital punishment for homosexuals in a speech he gave at Harvard.

While Rushdie has survived Tehran’s murderous intentions, many Iranian writers have been less lucky. Thousands were executed in the 1980s, and between 1989 and 1997, Intelligence Ministry agents killed dozens of writers and intellectuals who had dared to deviate from the path set by Mohajerani and his cohorts.

These days Mohajerani regularly appears as a pundit on BBC Persian Television. He often chastizes Israel. He also writes books on literature and novels in Persian and travels to various cultural conferences across the Islamic World. Despite his defence of the Iranian government, Mohajerani seems to have a good relationship with Saudi institutions. He’s a member of the Board of Directors of KAICIID, the Saudi King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue.

In 2015, Wikileaks published a letter sent by Mohajerani to the Saudi Embassy in London asking the embassy to support his son’s studies at Warwick University. Mohajerani’s wife Jamileh Kadivar called the letter a fabrication by Zionists and Israel, and added that “the criticism is not worthy of a response.”

In 2013, when Hassan Rouhani was elected president, the new Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance re-instated a portrait of Mohajerani on the wall of the ministry, which had been previously taken down. Mohajerani wrote a letter to the new minister to thank him, and also asked him to allow the publication of his books. He mentioned a novel, the Garden of Paradise, “which has been awaiting permission for years,” but also some of his previous publications — including that book he had written over the course of 40 days in 1989: A Critique of the Conspiracy of The Satanic Verses.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments

Mr Mohajerani is a hypocrite. he presents himself as an opposition to Iran's supreme leader and criticise the regime and appears on BBC Persian. However, he has a strong connection to Iranian embassy in London and former Press TV director in London.

Mr Mohajerani was in Lebanon this summer having various meetings with Hezbullah and Iranian officials.

All of the books that he has written are funded by Iran. he meets with Iran's informers in London on regular basis

Mr Mohajerani is planning to make a new programme sponsored by Iranian regime which is going to be broadcast in lran. the fund that the regime is going to put into this programme is enormous. ... read more