Arash is one of the old-time asylum seekers in Greece who has been through it all and does his best to help out fellow refugees.

In Iran he was a social activist who was imprisoned and tortured in Evin Prison for three years. When he was young, his father was assassinated and his brother executed.

He thought life couldn’t get any worse. But he has now been in Greece for more than two years and says he feels like a hostage.

I found him on social media. His page was full of news about refugees in Greece, and he replied quickly to my message. It was my second day in Athens and we agreed to meet at his home.

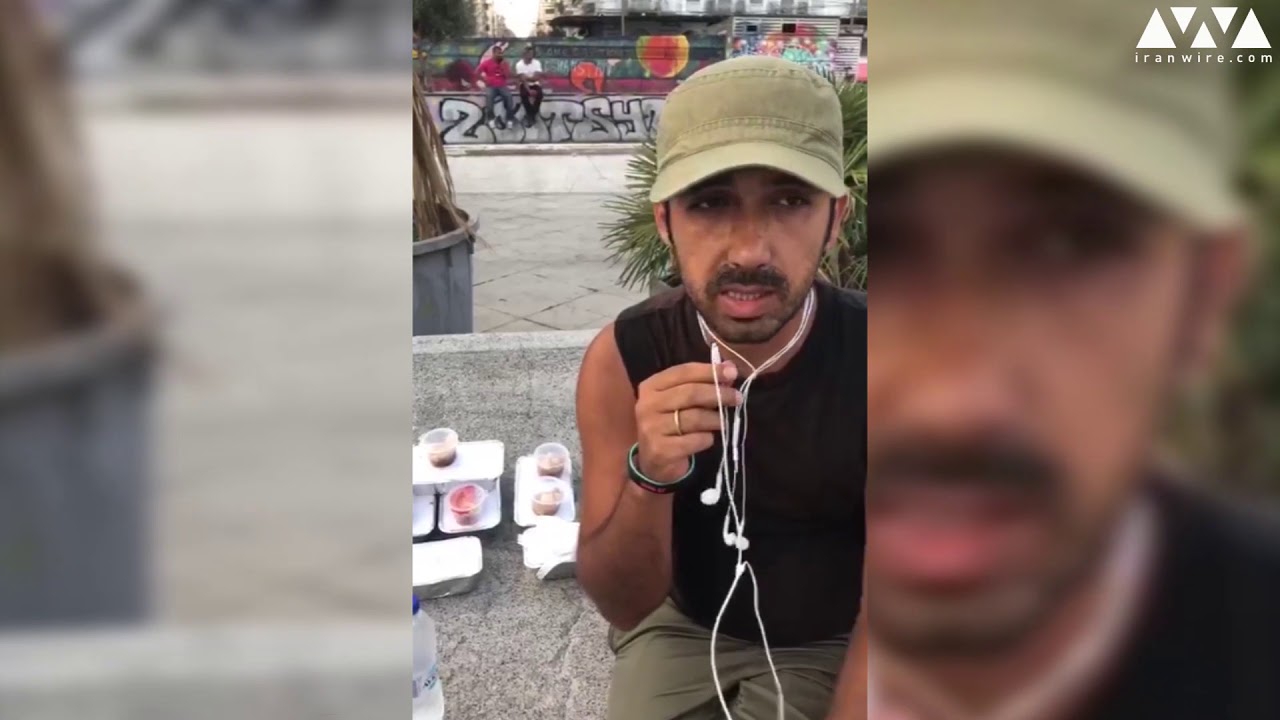

When I arrived, Arash was welcoming and humorous. He showed me his two-bedroom apartment, where he was hosting 12 asylum seekers, then took me to Omonoia Square. On our way we picked up 50 meals from a homeless charity, along with clothing and blankets.

Arash did this every night. He called the project “Our House”.

Every morning Arash received phone calls from asylum seekers who needed help. Some needed housing, others food, clothes or medical attention. After feeding his dogs, he would pack his rucksack and go out for the rest of the day to provide assistance to the homeless.

Arash started “Our House” project in Athens to provide food and assistance to the homeless.

During our conversations, Arash rarely talked about himself. Yet I gradually learned his painful story. His brother, Amir, has been stuck on Lesbos island for more than two years. Arash believed the government was holding him “hostage” as payback for his work for refugees.

A Pakistani family infected with Hepatitis C, who Arash helped to find a shelter.

A Family Torn Apart

Arash’s life has been a struggle from the start.

He grew up in Tabriz, in a neighborhood full of Basij militia and security agents. His father, Akbar, supported the Pahlavi regime and disliked the Islamic Republic. He owned a furniture store and was a member of a community council that provided single women with furniture and other day-to-day items.

One night the family was waiting for Akbar to come home for dinner, but he did not show up. In the morning, Arash’s uncle came to the house unexpectedly. He informed them that Akbar had been killed.

Arash, his mother, and his three brothers went to the police station. “The whole way my mom was sobbing,” Arash said. “The officers told us my father was trafficking a trailer full of drugs and he was killed in an armed struggle when passing across the border.”

The family hired an attorney to look into the case. The first two lawyers resigned before completing the investigation, but the third discovered that it was a 17-year-old Basiji called Mehdi Alipour who actually killed their father.

“The Basiji and a soldier were patrolling the neighborhood with a gun,” Arash said. “He told my father to stop on his way home and my father responded, ‘It’s late, young boy, you should not be out now – go home,’ and continued to pass them by.

“The Basiji was offended by this response. He took out his gun and shot my father through the heart from behind. He did not even make it to the hospital. This was the testimony of the soldier who was there that night.”

A week after the murderer was arrested, the Basij intervened and changed the charge from first-degree murder to involuntary manslaughter. The boy was released two weeks later. Afterwards, the family would often encounter him wandering freely around the neighborhood.

One year after their father’s death another tragedy struck.

Arash’s older brother, Javad, wanted justice for his father and would often argue with the Basijis. One night when they were expecting the 17 year old to return home, someone knocked on the door. They opened it to find a devastating scene.

Their brother had been hanged from a gas post in front of their home.

Torture and Abuse

The authorities registered Javad’s death as suicide. Shortly afterwards, they raided the house and arrested his other brother, Kazem, at the dinner table on charges of opium possession.

Kazem was sentenced to seven years in prison and a US$5,000 fine. Five years later he was released.

Between 1995 and 2012, Arash himself was arrested five times. His last arrest resulted in a three-year prison sentence for his work with refugees and the poor through his organization “Hamyaran Mehrandish”.

He was arrested on his way to work. Two cars with armed agents surrounded him and beat him on the roadside. They claimed he was smuggling opium. He was arrested at the scene and spent the next six months in solitary confinement.

Arash in Ward 350, Evin Prison.

Arash was taken to Evin Prison and tortured frequently. This included three staged executions, threats to murder his family, and heavy beatings that resulted in damaged kidneys and testicles, and the loss of 11 teeth.

His eyesight was also badly affected after he was hit over the head with a hard object.

There is an infamous day in Evin’s history known as “Black Thursday”, when guards violently assaulted every prisoner in Ward 350. Arash experienced this day first-hand and later wrote an open letter about the incident.

“But the most painful torture was the fact they did not let me call my family and tell them what had happened for a whole month,” he said.

“They told me my mom had passed away. But the poor woman had searched everywhere for me, from hospitals in Tehran to cemeteries in Tabriz. She aged 100 years during that month.

“They finally gave me a phone call for 10 seconds, when I could call her and tell her that I was alive and in Evin Prison.”

When he was released after three years, Arash continued to help the poor and homeless. Intelligence agents began harassing him again, and after four months he was summoned by phone to the Revolutionary Court.

He could not go to prison again, especially as he knew that this time the sentence was likely to be worse. So he and his mother decided it would be best for him to leave Iran.

He packed his bag with a few books he had received from friends in prison and headed for the border. On January 2, 2016, his life as an asylum seeker began.

From One Prison to Another

“I went to Khoy,” he said. “The trafficker came and picked me up. I did not know anything. I didn’t even know what the next step would be and what country I was going to. But I was tired of spending my youth in a prison cell.

“The trafficker handed me over to another guy at the border and they housed me in a stable along with 40 Afghan travelers. The next day we headed for the mountains.

“It was winter and I was walking in snow that reached my knees. We walked for eight hours until we reached Van. A human rights activist came for me and got me a bus ticket to Ankara.

“I was lucky, but not all of us were. Before reaching Van there were times when the border patrols were shooting right at us. So many people got arrested and four were deported.

“My mom’s face was in front of my eyes the whole way. My only thought was that my mom was now lonelier because of this decision and she was spending all her time crying. I thought I would never be able to see her again.

“My roots were back in Iran. My memories, my childhood, everything. I was completely desperate and disappointed. I felt like a loser who had lost everything.”

Arash went to the Turkish city of Eskişehir and lived there for seven months. But he felt insecure in Turkey so he decided to continue onwards.

His brother, Amir, joined him in Turkey as he too had been harassed in Iran for his activist work. They decided to go to Greece together.

“The trafficker did not even tell us where he was sending us,” said Arash. “He told us to get on the boat and a man named Ehsan and his wife would pick us up at the other side and take us to their home. They would then give us our plane tickets so we could fly to our final destination.”

He added: “We are still waiting for the couple.”

Thoughts of Suicide

At 6 am, Arash, Amir, and 44 other people boarded an inflated boat with a capacity of 20. Among the group were pregnant women, children, and the elderly. Some of the travelers, including Amir and Arash, did not even have a life jacket.

In the middle of the sea, the Turkish coastguards spotted them and tried to send them back to Turkey by making waves against the boat. However, their captain knew what he was doing and managed to maintain control.

Some of the travelers lifted their children into the air to show the coastguards how many were on board. This seemed to help, as afterward, the patrol boats left them alone.

All the passengers arrived safely at the other end, unaware of the new prison that awaited them.

After arriving at Lesbos, asylum seekers are arrested and sent either to jail or a refugee camp called Moria. Human traffickers don’t talk about the island because it is known as a place where refugees become trapped.

Refugees have to wait for many years just to get permission to go to Athens. Some traffickers charge more to transfer refugees straight to the capital. But they often can’t deliver and their clients get caught on Lesbos nonetheless.

Lesbos is one of the worst refugee camps in the world. After living here for a few months, many refugees opt to return to Turkey.

Arash in the refugee camp on Lesbos island.

Arash and his brother, along with 150 other asylum seekers, spent 28 days in a quarantine tent designed to house 50. The portable toilets were installed inside the tent.

In total, they spent seven months living in the camp. The tents were flimsy and often collapsed under the wind and snow, leaving residents without shelter.

“I’ve been tortured and harassed for 30 years in Iran, but staying in this camp for only seven months made me want to commit suicide,” said Arash.

A Swamp for Refugees

After seven months, Arash was granted permission to leave the island. However, his brother received a deportation letter and was arrested. Instead of leaving, Arash went on hunger strike for 42 days until his brother was released.

At the same time, other desperate asylum seekers attacked and occupied the office of SYRIZA [Synaspismós Rizospastikís Aristerás: The Coalition of the Radical Left]. They were all arrested and Arash again went on hunger strike to support them – this time for 68 days.

In negotiations with EU representatives, he agreed to end his strike when all the asylum seekers received permission to go to Athens. However, they would not agree to include Amir.

“They told me that if I didn’t end my strike, I wouldn’t be able to see my brother anymore and they would deport him back to Iran. I had to accept their offer because it was not only about my brother and me. So many others would benefit from my agreement with them.

“However, Amir is still a hostage on the island. If they reject his case this time, he will be deported back to Iran and no-one can do anything for him.”

After spending two years in Greece, Arash says asylum seeking is the wrong phrase to refer to the situation in this country.

“Greece is not a destination for asylum seekers. It’s supposed to be a temporary stop. But they took us hostage to make some money out of us.

“The EU pay the Greek government for each asylum seeker, which turns us into a stream of income for the country. We are hostages here. Greece is a swamp for refugees.”

Asylum seekers in Omonoia Square being helped by volunteers in Athens.

Arash gives his definition of an asylum seeker. “It is a person who has nobody and is truly alone with nothing to lose. No country, no community, no family, no security.

“Asylum seekers live with constant stress and have to endure contempt from others. If the fascists don’t beat us up, they humiliate us with their attitude towards us.

“As an asylum seeker myself, I try to help out the homeless here since their government does nothing for them. So what can we expect?”

He continues: “Greece is not a European country. It’s more like a Middle Eastern one. Many of the people stuck here for months or years don’t have a debit card or access to medical services. They don’t even have anyone taking care of their case.

“A single man here is worth nothing. You have to either be a thief or die.

“On the other hand, there are many Iranians with no serious problems back home and when they can’t endure the situation here anymore, they just deport themselves back to Iran.

“This makes the process harder for us, as the human rights organizations don’t trust Iranians as much. So this is a reason for them to postpone our cases, to check who’s a real refugee and who is not.”

“I Will Always Do My Best to Help Others”

Arash has lost so much during this journey, he said. “The real Arash was left behind in Iran. I turned into a robot here. I was a romantic man, but nothing can bring romanticism back to me. I am a depressed person now with a shattered life.

“I left part of my heart back in Iran with my mom, and the other part on Lesbos with my brother, and a part in Germany with my girlfriend. I don’t have a soul anymore. I really want to go back to Iran from the bottom of my heart, but it’s not possible

“I have never regretted my choice, but this does not mean I don’t want to go back to Iran. I have wanted it ever since I set foot on this journey. This was not a free choice for me. It was my only option. But I have no hope for the future.”

Arash spoke about his dreams. He dreamt of having a backpack with a camera and the ability to travel freely. He dreamt of a day when his city would be free of homeless or hungry people.

“I will always do my best until the end of my life to be of help to the less fortunate, like homeless people, addicts, and refugees. People who are never noticed or helped out by anyone. People who have been forgotten.

“This is what helps me to go on each day.”

Read the latest about Arash Hampay and other stories in the series:

Iranian Refugee Rights Activist Faces Long Prison Sentence in Greece, January 28, 2019

From Asylum Seeking to Asylum Dealing, January 23, 2019

A Lost Life: Why was Pedram Safari Left to Freeze to Death?, January 21, 2019

Through A Child’s Eyes: Crossing from Iran to Turkey, January 14, 2019

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments