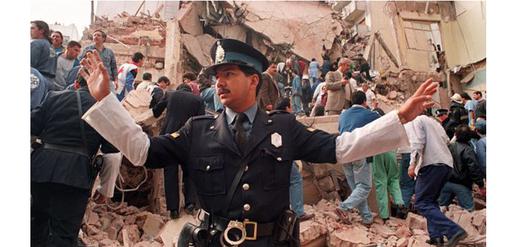

Last Sunday, January 18, Argentine Federal Prosecutor Natalio Alberto Nisman was found dead in his apartment, just hours before he was due to present evidence to Congress about the July 18,1994 bombing of the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association (AMIA) in Buenos Aires. The terrorist attack, which killed 85 people and injured hundreds, was the worst in Argentina’s history.

Nisman, who led the investigation, had accused Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and other top officials of covering up vital information about the attack in exchange for trade deals with Iran.

Iran is widely believed to have ordered the atrocity by instructing its Lebanese militant allies, Hezbollah, to carry it out. In 2006, during the presidency of Kirchner’s husband Néstor Kirchner, Nisman and another prosecutor, Marcelo Martínez Burgos, launched formal charges against the Iranian government and Hezbollah, but no one has ever been prosecuted for the crime.

Nisman’s body was found in the bathroom of his apartment in Buenos Aires. Authorities found a firearm and .22 caliber shell casing next to his body. An autopsy report released on January 20 concluded that Nisman had committed suicide. After initially supporting these findings, Kirchner said on January 22 that she did not believe he had committed suicide. No gunpowder was found on Nisman’s hands, and he did not own the gun that was found beside his body.

Many questions surround the case. IranWire has endeavored to outline the twists and turns of an extraordinary series of events that has shaken Argentinian society.

Did Nisman uncover incriminating evidence that could jeopardize Argentina’s elite?

On January 14, Nisman accused President Kirchner of covering up Iranian involvement in the 1994 attack. Nisman said the president and her foreign affairs minister Hector Timerman hoped to seal a trade deal with Iran, allowing Argentina to buy cheap oil in exchange for grains and other food.

Timerman was said to have talked to Interpol about discarding arrest warrants for Iranian officials implicated in the attack, something he denies. Nisman claimed to have identified new evidence of the cover-up, and his report documents a meeting in Aleppo, Syria, in January 2011, between Timerman and Ali Akbar Salehi, Iran’s former foreign minister. It was at this meeting, according to Nisman’s official complaint, that Argentina expressed its willingness to stop pursuing Iran’s involvement in the AMIA attacks.

Previous evidence — cassette tapes that showed Argentinian intelligence agents knew an attack was planned — had allegedly disappeared. On January 19, Nisman was to present new evidence to a congressional hearing.

According to Kirchner, Nisman’s report contained false information. “Nisman’s accusation not only collapses, but it becomes a real political and legal scandal,” she said. Secretary to the Presidency Aníbal Fernández has said she does not believe that Nisman was the author of the official complaint against the government.

In one of the transcripts Nisman supposedly intercepted, union leader Luis D’Elía said the government might be willing to bring in representatives from Argentina’s national oil company to further negotiations with Iran. D’Elia, a Kirchner supporter, said he was acting on orders from “the lady in charge.”

Other evidence reveals negotiators discussing ways of blaming right-wing groups for the terror attack, and another refers to possible exchanges for not just grains but weapons as well.

Congresswoman Elisa Carrio spoke of the death as "a mafia sign” — and some protesters reiterated the comparison with the infamous Italian organized crime network. Congresswoman Patricia Bullrich said Nisman had told her he was repeatedly "threatened".

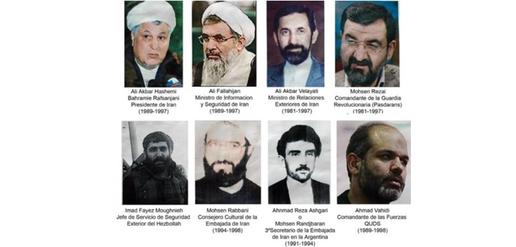

It is not only Argentina’s political elite that has come under fire. Nisman accused businessman Jorge Alejandro Khalil of covering up the AMIA bombing. According to the 300-page report submitted by Nisman in mid-January, Khalil shifted suspicion away from Iranian officials in order to resume trade links between Argentina and Iran. Of particular interest to Nisman was Khalil’s links with Mohsen Rabbani, a former Iranian cultural attaché implicated in the attack.

How will these accusations affect Iran’s efforts to engage with the international community?

Nisman’s view that Iran and Hezbollah were behind the AMIA attack is widely supported by intelligence officials around the world. Iran has always denied involvement. Although no one has been charged with the attack, Argentina has had a fractured relationship with Iran — and the Argentine Jewish community has continued to push for investigation.

According to some reports, Nisman’s findings suggest that Hassan Rouhani sat on the 1993 National Security Council panel that allegedly planned the attack, along with other prominent figures, including former Defense Minister Ahmad Vahidi and 2013 presidential candidate and former military commander Mohsen Rezai, both of whom were on an Interpol “red notice” list. Some reports have said six Iranians were implicated in the attack. If Iran did order the attack, the Supreme Leader was also directly involved.

According to Nisman, Iran and Argentina were planning to enter a trade agreement in exchange for impunity for Iranian officials involved in the attack. The deal allegedly fell through because Interpol could not be persuaded to take the Iranian officials off its wanted list.

Rouhani’s moves to discuss nuclear (and other) issues with the West, and to rehabilitate Iran’s image abroad, have faced fierce opposition from Iran’s hardline politicians and media. For the Rouhani administration, revived interest in the 1994 bombing represents a setback. It will hinder Iran’s efforts to gain influence in Latin America, which it has been trying to do over the last few years, particularly in Brazil, Bolivia and Venezuela.

Both the Rouhani administration and the office of the Supreme Leader have chosen to stay quiet on the matter.

What does the public outcry mean for the future of Argentina?

Thousands of people have taken to the streets to condemn Nisman’s death, some of them holding signs that read, “We are all Nisman. Will you kill us all?”, “No more lies!” and “Enough, Kirchner!”

Protesters convened in the iconic Plaza de Mayo in downtown Buenos Aires, as well as in the provinces of Santa Fe and Cordoba. Though the protests were largely peaceful, there were sporadic clashes with police, including outside the government building Casa Rosada, where demonstrators knocked down barriers. Events this week have reminded the public of the government’s failure to bring the perpetrators of the atrocity to justice. “Whether he was killed or he took his own life is irrelevant,” said one protester, “As a nation we aren’t conscious of the importance of protecting our justice system.”

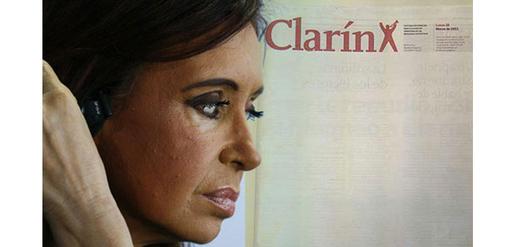

Argentina’s divided media landscape will continue to play a role in deciding how the public views the government, and how domestic and international politics play out. The Kirchner administration has a long-running battle with Grupo Clarín, the country’s largest media conglomerate, commanding about 44 percent of the market. President Kirchner lashed out at Clarín last week, which ran a series of front pages attacking the administration.

The head of the Delegation of Argentine Jewish Associations, Julio Schlosser, said President Kirchner’s admission that Nisman’s death was not a suicide served to “raise more doubts" about the case. Schlosser and AMIA Jewish center leaders demanded clarification and the truth on Nisman’s death and on the AMIA case. "We are tired of not having answers. What we want is the truth and the truth seems far away”.

What did Iran have against Argentina?

It all goes back to nuclear deals. Tehran was said to have been furious when Argentina said it would no longer cooperate with Iran because its nuclear program was not solely for peaceful purposes. But there were also reports that the two countries had renewed discussions in 1992.

Has anyone challenged Nisman’s reputation?

Was Nisman pushing a US-led agenda? Could he have been under the influence of a former intelligence agent? In a secret cable published by Wikileaks, it was revealed that Prosecutor Nisman had a close relationship with the US embassy, suggesting a geopolitical agenda that was not apparent before. Correspondence between the US Embassy in Buenos Aires and the US State Department outlined Nisman’s visits to the embassy and to the United States, during which he discussed details of the AMIA case with US officials, reviewing legal documents before they were presented to the Argentinian judiciary. Former Supreme Court judge Eugenio Zaffaroni has said that Nisman was “a victim of twisted facts...I have no reason to believe he did this maliciously. At some point he had to realize that he was wrong.”

Nisman’s complaint was dismissed by official news agency Telám as “labyrinth of inconsistencies,” stating that at least one of the people Nisman had named as an intelligence agent was not actually employed by the bureau. It also argued that, contrary to Nisman’s claims, the government could not have wavered any grain deals with foreign suppliers — that was up to Argentine agribusinesses, and the government would have had to bring them in, something that would mean their secret deals could not go ahead in secret.

When Nisman made his accusations, Minister Timerman countered that the prosecutor was under the influence of former secret agent Antonio Jaime Stiuso, who the government dismissed in December 2014. Special attorney Nisman had asserted that the 2013 Memorandum of Understanding between the two countries was an attempt to put an end to the Interpol order to arrest the Iranian suspects in the AMIA bombing, an interpretation Stiuso is said to share. While at the agency, one of Stiuso’s responsibilities was to help Nisman with the investigation into the 1994 bombing. In his official complaint, as Telám reported, Nisman named two intelligence agents— Héctor Yrimia and Ramón Allan Héctor Bogado — as being involved with the cover-up. The Intelligence Secretariat denied that the two men were actually employed by the agency. The names were said to have been supplied by Jaime Stiusso.

Some US officials, including one former FBI official, have questioned the claim that Iran was directly involved in the attacks. Influential union activist and Kirchnerite Luis D’Elía has also publicly questioned Iran’s involvement. D’Elía was said to be one of the key negotiators in Argentina’s discussions with Iran.

Will Nisman’s death force Argentina to be more transparent?

Argentina’s head of intelligence, Oscar Pariilli, has said that evidence collected by Nisman — namely the CDs containing the recorded wiretaps and other documents — must be preserved. Judge María Servini de Cubría arranged for "the declassification of the identity, actions, events and circumstances relating to intelligence personnel that arise from the recorded telephone calls.” The material is now in the public domain.

The Argentinian public would embrace more transparency, especially when it comes to the AMIA investigation. The case has been marked by incompetence and repeated accusations of cover-ups and corruption. Federal Judge Juan José Galeano, who was originally tasked with the case in 1994, ordered the arrest of Carlos Telleldín, who is alleged to have provided the van used in the bombing, and some 20 officers from the Bonaerense Police. Later, a video broadcast on Argentine TV showed the judge offering Telleldín $400,000 in return for evidence.

Former President Carlos Menem (1989-1999) was charged with "overstepping the functions granted by the constitution” for blocking investigations into possible “Syria connections” because Syria allegedly contributed funds for his election campaign. Menem is of Syrian descent. Iranian embassy officials in Argentina were thought to be involved in the derailing of the investigation.

Writing on Facebook on January 19, President Kirchner said that Nisman’s death — which, at the time, she was still referring to as a suicide — will be met with “shock and questions — but also a story too long, too heavy, too hard and above all, too sordid.” Defending her dismissal of accusations as “ridiculous,” President Kirchner said it was “conspicuous and suggestive” that, just as the trial concerning any alleged cover-up was about to get underway, people from certain sectors of society were “trying to accuse the government that has done the most... to solve the case” of obstructing justice. She said there had been attempts to “divert, lie, cover up and confuse” the people of Argentina.

What good is a Truth Commission?

In 2013, Iran and Argentina signed a controversial Memorandum of Understanding, agreeing to re-open the AMIA terrorist attack case and to create a Truth Commission, which would be made up of independent judges from other countries. The agreement was contentious among many Argentine politicians and members of the public, who saw it as a collusion with those responsible for the atrocity. Last year, a court found the agreement to be unconstitutional, a verdict the government planned to appeal.

Amid last week’s allegations, President Kirchner insisted that the memorandum was “the only way to unlock the investigation.” But in a radio interview on Thursday, January 15, a day after filing the case and his 300-page report, Nisman said the 2013 agreement “was presented as something to help unblock the negotiations and ended up being a criminal deal of impunity.” The agreement, he said, was “a way to introduce a false lead” into the probe.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments