Military officials routinely describe Iran’s compulsory military service as an important time in a young man’s life, a sacred period in their lives when they serve their country out of duty and honor. The mandatory service is, officials are fond of telling the public, the best way of preparing the country’s young people for the possibility of war, readying them for the battlefield should the need arise. But ask anybody who has served — especially those from Iran’s minority groups — and it is immediately apparent that this account is far from the truth.

When I was serving in the military, I came to know a young Baha’i recruit named Sahba. He would occasionally confide in me. “In Iran, a Baha’i has no right to work, has no right to education, has no rights at all,” he said. “If he is murdered, his family is not entitled to his blood money. Why must he serve in the military like other people? Why should he guard the families of the officers in their residential complexes? Do they protect him?”

It used to be that families viewed military service as a way to turn irresponsible boys into responsible men. But, for most families, over the last 20 years, military conscription has become a synonym for coercion. The severity of this coercion depends on a range of factors including ethnicity, beliefs, religion, marital status, education and the social and financial situation of the conscripted soldier. One former conscript says his duties and those of his fellow soldiers included everything from “helping to write college dissertations to guarding the officers’ residential complexes to gardening and cleaning houses.” This unpaid labor and abuse of the system are bad enough, but when it comes to minority conscripts, the situation is even worse — especially for members of unrecognized religious minorities, who are officially referred to as citizens but are actually stripped of all legal rights.

It is difficult to comprehend or believe the extent to which Sahba and others have been pressured, and the discrimination they have faced from their commanders. Unit officers refused to even give Sabha food on a daily basis; the other soldiers and I often shared our meals with him.

But the neglect and abuse did not stop there. After Sabha had served for a short period, barrack commanders prepared to send him to the town of Kahnuj in the southwestern province of Kerman to improve the town’s smuggling problem. Sabha knew that he would be treated even worse if he were sent to Kerman; most soldiers do not want to be placed there. The officers gave him his reassignment papers and sent him to the garrison commander’s office for the final signature. When Sabha arrived, the commander was busy talking on the telephone. When he finished, he asked Sabha where he was being transferred. Sahba — who had nothing to lose — took advantage of the distraction and said, “I am part of the process of reorganization and will return to my birthplace, Tehran.” The commander wrote down “Tehran” and signed the form.

In Tehran, Sahba had somewhat better luck. The moment he arrived, his good-natured superior selected him as his deputy, meaning he had slightly less to worry about. But when his superior was away, the harassment continued as before, so much so that once he resorted to burning himself with boiling water in order to request a leave of absence. In our last communication, he called what had happened with his reassignment form a “miracle” and said, “the worst things that happen in Tehran’s garrison are better than exile in Kahnuj.”

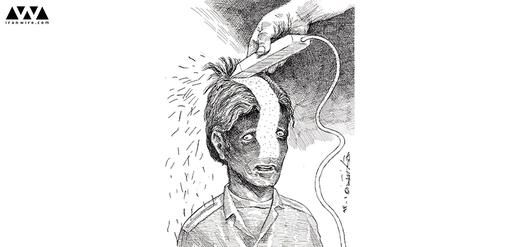

Suicide and Self-harm

A simple Google search for “soldier suicide” in Persian language produces a number of entries, lists of stories covered by Iranian news agencies reporting “suicides by soldiers from the Zionist regime” that were following “barbaric missions,” or suicides by Afghan or Turkish soldiers.

But, apart from human rights websites or a few blogs, Iranian media does not report on this taboo subject. It is difficult to find information about what Iranian youth have to deal with during military service.

Hekmat Safari, a member of the Yarsani minority religion, was among those who committed suicide. The Yarsani faith has about a million followers, and they mainly live in the border areas between Iran and Iraq. At time of his suicide, Safari was serving with the Revolutionary Guards in Bijar in the Iranian province of Kurdistan.

According to a report by Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA), Safari committed suicide by shooting himself with his army-issued gun in spring 2014, following repeated harassment by his superiors and commanders. A source close to Safari told the HRANA reporter, “Commanders and authorities at the barrack insulted his religion and harassed him. Hekmat had called his family to tell them what was going on before committing suicide.”

According to a study by an Iranian medical journal, there is a direct correlation between suicides and reports of senior commanders psychologically and physically abusing conscripted soldiers. The report also says that “the geographic location of the base, the level of solidarity among soldiers and how much the soldiers have in common” also affect suicidal tendencies among soldiers.

In addition to suicide, there are high numbers of incidents of self-mutilation. Many soldiers maim themselves as a way of being exempted from military service.

“There are no accurate statistics about suicide and self-mutilation among Iranian soldiers,” a sociology student who has done research on the subject told me. “The military system currently in place prevents any information from being published. It prevents the distribution of reliable statistics that might actually be useful to produce sound studies on the subject. Even so, the small number of published reports that are available lead us to believe that ethnic and religious minorities represent a high percentage of the victims.”

Baha’is, a Minority among Minorities

“If you spent just one week there, you would get the picture,” Omid, a solider currently serving his compulsory military duty told me. “Commanders exploit others and try to get some relief from their own psychological problems by harassing others.” Most officers abuse their powers, he said.

“Commissioned officers lead these divisive practices,” he says. “They give seniority to the meanest soldiers and allow them to treat other soldiers miserably. So soldiers from a specific city or province have their own gangs to protect each other— and they don’t trust anybody outside their gangs. Trust and comradeship in the barracks is meaningless. The law of the jungle rules. Everybody tries to save himself, even if the price causes trouble for others.”

One Baha’i soldier, Mahyar, told me about his experience as a conscript. Mahyar is from the port city of Nowshahr on the Caspian Sea but serves in northwestern Iran. “Most of the soldiers in our garrison are Muslims and Turkish-speaking and of course have Pan-Turkist habits and culture,” he says. “As a Persian-speaking Baha’i, I am a minority in every way. I cannot even really understand what they are talking about. From the first day that I was sent there almost all soldiers hated me, spurred on by the discriminatory policies of the government.

Mahyar tried to establish a rapport with other soldiers. “I tried friendship,” he says. “I thought if I they found out that I am a Baha’i and therefore belong to a minority in Iran they would accept me. But from the first moment that they became aware of my faith they wanted me to get out of their dormitory. This has now happened to me three times. Nobody wants to be ‘polluted.’ I don’t understand how in such an inflexible system the demands of the soldiers have become so important for the garrison officials.”

For officially recognized minorities in Iran, the problems are less severe. “For Armenians military service has a positive side,” says Aron, an Armenian Christian. “For example, we can take a leave of absence for religious holidays and occasions. On the other hand, we have to attend ideology classes. Sometimes they say things that offend our beliefs and upset us.”

Burying the Tragedies

Much of the abuse and discrimination against minorities during their period of military service is covered up, buried in the grounds of the barracks. “What is the use?” many people say, justifying their refusal to speak up. Many are forced to self-censor out of fear or in deference to social taboos. One example is that of Farshad, who told me what happened when people found out he was gay.

“What happened during my military service was more like a nightmare than realty,” he told me. “The personnel, the soldiers and even the cab drivers outside the barracks harassed me. They knew how much it must be hurting me. After a lot of bureaucratic efforts, they eventually let me go seven months early.”

There are many other examples. Karim Ghasem-Nejad, a young Kurdish man from a village near Salmas in West Azerbaijan committed suicide. The police delivered his body to his family in early February 2013, told them their son had killed himself, but gave no explanation for the burn marks and bruises on his body.

“If Karim had really committed suicide, then why were there burn marks and signs of beating on his body?”, one relative asked. “Why did the Intelligence Unit of the Revolutionary Guards prevent his funeral from taking place? We filed a complaint to bring the barracks officials to the court but after three years, the case has got nowhere.”

About a year ago, the same thing happened to Nasser Isa-Zadeh, also from Salmas. His death was declared a suicide but he had burn marks around his neck and his waist, and his legs were broken. The Intelligence Unit of the Revolutionary Guards once again prevented a public funeral and his family filed a complaint in vain.

According to a report by HRANA, which quoted a relative of Isa-Zadeh, he was accused of “activities against national security, trying to cross the border illegally and escaping military service.” According to the relative, Isa-Zadeh had simply got into an argument with a commander.

Something similar happened to Benyamin, a young Baha’i soldier who dared to get into a debate during ideology class. He was abused and bullied the full 18 months of his military service.

For some, the training exercises and camaraderie of military duty results in lifetime friendships and good memories. But for those conscripts from ethnic, religious and sexual minority groups, it is more often than not a period of pain, hardship and torture.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments