Mohammad Khatami is one of the most popular politicians in Iran. When he was president from 1997 to 2005, he increased social freedoms and promoted a well-received “dialogue of civilizations” with the West. Today many Iranians remember him fondly, but Iran’s security officials appear to see him as a potential threat to the state. Iran’s official media no longer dare to mention his name, and his relations with the Islamic Republic itself have become a confusing puzzle.

The events of the past seven years tell the story of a man neither fully accepted within Iran’s official circles, nor cast out entirely.

Khatami’s current troubles began following the contested presidential election of 2009, in which he supported the reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi. When Mousavi lost to incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, millions of Mousavi supporters, along with supporters of another reformist candidate, Mehdi Karroubi, accused the state of electoral fraud. When Mousavi and Karroubi joined in protests against Ahmadinejad’s reelection, Iranian hardliners and security officials accused them of “sedition.”

Iran's ruling clerics wanted Khatami to condemn Mousavi and Karroubi, but he has never done so.

Because of his association with Mousavi, the Iranian judiciary banned Khatami from leaving Iran, and banned the media from publishing his photograph or quoting him.

Yet just two months ago, Khatami was working in a small office in Tehran’s Yasser Street, which is home to the Supreme Reformist Council for Policy Making (SRCPM). The SRCPM was the most important reformist decision-making organization involved in campaigns ahead of February’s elections for Parliament and the Assembly of Experts. In those elections, Khatami played the role of godfather to reformists, who considered him their leader and obeyed his guidance.

And Khatami remains heavily involved in reformist affairs. He runs an organization called the Advisory Council, which has functioned in recent years as an effective reformist think tank. As chairman of the Central Council of the Association of Combatant Clerics, he is well positioned to mitigate differences within the reformist camp. He also plays a supervisory role in facilitating entry of newly founded reformist organizations and other political groups into the SRCPM.

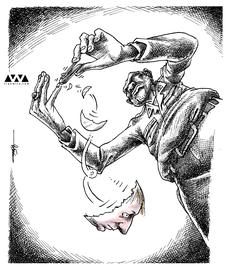

Khatami’s popularity with reformists was everywhere in evidence during February’s elections. One manifestation of his celebrity was an eye-catching reformist poster that bypassed censorship of Khatami’s face by showing only his hands (which were identifiable by a trademark ring). His supporters also published a video message from him on Facebook, Telegram and other social media.

In his video, Khatami acknowledged that the elections were not ideal in terms of the high number of candidates disqualified by Iran’s Guardian Council, but encouraged people to vote for what he called the “List of Hope” drawn up by reformists.

On Election Day, supporters mobbed him when he went to cast his vote at a polling station in northern Tehran.

Ever since his presidency, Khatami has tried to play kingmaker through compromise, often with success. During the 2013 presidential election campaign, he convinced his own former first vice president, Mohammad Reza Aref, to withdraw in favor of Hassan Rouhani.

Yet for all his participation in Iran’s official politics, many of Iran’s security officials and hardline politicians view Khatami with suspicion. Just a few days ago, security officials prevented him from attending the wedding of the Nargess Mousavi, daughter of the Green Movement leader Mir Hossein Mousavi, who has lived under house arrest with his wife, Zahra Rahnavard, since 2011.

The Third Point in a “Sedition Triangle”

After the events of 2009, many angry reformists and moderates debated whether to vote in future elections at all. But in 2012, Khatami made a point of voting in parliamentary elections, thereby sending reformists a message in favor of voting.

In the run-up to that election, hardline politician Gholam Ali Haddad-Adel had actually asked Khatami to coordinate reformist candidates. This was highly unusual because, since the 2009 elections, hardliners had described Khatami as the third component in a “Sedition Triangle” along with Mousavi and Karroubi. This episode shows that the Islamic Republic has continued to find use for Khatami during election seasons, as long as he has kept a low profile.

Now that elections are over, however, Khatami’s status may be changing for the worse. In his election message, Khatami had expressed hope that the elections would clear up “misunderstandings.” Now, if security officials’ decision to prevent him from attending Nargess Mousavi’s wedding is anything to go by, it seems “misunderstandings” have intensified.

It may be that Iran’s security establishment fears that giving Khatami room to maneuver is risky because of his popularity. It now appears that security officials want to “clip his wings,” to borrow an expression hardline Guardian Council Chairman Ahmad Jannati used with regard to Moussavi and Karroubi.

The wedding ban may foretell a plan to limit Khatami’s contacts with his associates, or even put him under virtual house arrest.

But that hasn’t happened yet. One test of this theory will be to see if authorities shut down Khatami’s office. Another will be to see how they deal with Khatami’s participation in meetings of the Association of Combatant Clerics.

Elections as a Marathon

One popular theory among Khatami’s critics is that the Islamic Republic is using Khatami and his social appeal to encourage people to vote in elections, and thereby shore up the legitimacy of Iran’s political system.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ai Khamenei has repeatedly urged high voter turnout, which for him is synonymous with political competition. He says elections are a “marathon,” and that the more people participate, the more vigorous the competition will be.

Of course, there is more to elections than voter numbers, and Khatami’s presence as a symbol may have negative as well as positive consequences for the regime.

For one thing, Khatami’s popularity waxes and wanes. During the parliamentary elections of 2008, his name and picture were at the top of the reformists’ list of candidates, but failed to spark much enthusiasm.

In the 2013 elections for Tehran City Council, the “symbol” of Khatami's name on an electoral list failed to translate into an electoral victory for moderates. The election was largely overshadowed by the presidential election, in which Khatami played only an intermediary role.

But in the 2016 elections for Parliament and the Assembly of Experts, it is clear that reformists did accept him as a full-fledged leader.

Hardliners, meanwhile, often fail to understand their opponents’ tactics. Sometimes they even unwittingly help the opposite side, for example by retreating into conspiracy theories. This election season, they claimed reformist candidates were part of an “English List” of candidates, which was supposedly drawn up by Iran’s enemies in London. But it was in large part due to Khatami’s role in elections that hardliners endured a crushing defeat in Tehran.

In view of the current electoral paralysis of the hardliners, and of the more professional electoral behavior of people who support Khatami, it seems unlikely that Khatami is merely a pawn in the hands of the regime.

Related Articles:

comments