- Recently published audio clip not only offers fresh insight into the 1988 massacre — but also sheds light on how the political fallout of the time shaped Iran’s political landscape today.

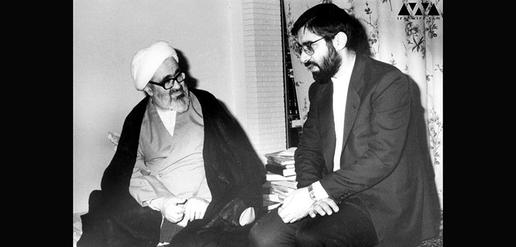

- Ayatollah Khomeini’s relationship with Ayatollah Montazeri was contradictory and unpredictable.

- Did Khomeini and Montazeri fall out because of a battle over human rights, or something that had more direct impact on Montazeri’s extended family?

- Prime Mir Hossein Mousavi, who later led the Green Movement, gave full support to Khomeini, but purported to know nothing of the killings.

- Though Mousavi and Montazeri later shared an enemy in Ayatollah Khamenei, they failed to take the opportunity for an alliance when it might have had an impact.

Seven years after his death, Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri — once heir apparent to Ayatollah Khomeini — is back in the news.

On August 10, the office charged with managing Montazeri’s affairs and legacy released an audio file from 1988. In the clip, Montazeri is heard arguing with three members of the so-called “death panel,” who had been appointed by Ayatollah Khomeini to carry out mass executions of political prisoners in the summer of that year.

At that time, three other figures were center-stage in Islamic Republic politics: President Ali Khamenei, Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi and the Speaker of Parliament, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

So what was Montazeri’s relationship with these four prominent figures? And what really went on between him and Ayatollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic?

“Everybody knows you are the fruit of my life’s work and I am deeply fond of you,” Ayatollah Khomeini wrote to Montazeri in a letter on March 28, 1989. Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani — who today heads the Expediency Council — bears witness to this claim. “Imam [Khomeini] was more fond of Mr Montazeri than of any one of us,” he wrote in his memoirs. Rafsanjani said that Montazeri and Ayatollah Morteza Motahari, who was assassinated soon after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, were Khomeini’s “most favorite pupils.”

But just two days before Khomeini’s letter to Montazeri, he had had written another, less generous, letter to his beloved pupil. “You are a simpleton,” the founder of the Islamic Republic wrote to Montazeri. “From the start, I was against choosing you [as the deputy supreme leader]...I considered you a simpleton and I knew that you were not a wise leader.”

These contradictions — charged with emotion, whether expressions of long-standing love or eternal hatred — characterize the relationship between the two men until its abrupt end in 1989.

The Utmost Respect

In his memoirs, Hashemi Rafsanjani recounts a meeting when Khomeini and Montazeri clashed over various policies. “Imam was very kind to Mr. Montazeri and told him that he was essential to the revolution and ‘safeguarding your credibility is the duty of us all,’” he wrote, one of many accounts of Khomeini’s respect for Montazeri. Another is a letter Khomeini wrote to Montazeri in March 28, 1989: “I believe it is in the interest of you and of the revolution that you should function as a Faqih [Islamic jurist] for the benefit of the people and the system.”

Before the 1979 revolution, Khomeini not only appointed Montazeri as his plenipotentiary representative but also asked him to manage his “household”, meaning his office in Qom and his personal affairs.

Insults between a “Simpleton” and a “Bloodthirsty Murderer”

So why did Khomeini also insult Montazeri, dismissing him as a simpleton who he would never choose to succeed him?

In the autumn of 1986, Montazeri wrote to Khomeini, asking him to leave him out of state affairs. But the supreme leader refused to accept Montazeri’s letter of resignation.

Although Khomeini appointed Montazeri to represent him and oversee his affairs prior to the revolution, in 1988, he wrote that Montazeri’s own “household” was made up of “liberals” and traitors to the Islamic Republic, including members of the People’s Mojahedin Organization (MEK), one of the Islamic Republic’s most long-standing and controversial opponents. MEK Thousands of MEK members were killed in the mass executions of summer 1988. “From now on you do not represent me,” Khomeini said. He even told the conservative cleric Ruhollah Hosseinian: “Mr. Montazeri is corrupt himself and he educates his pupils to be corrupt as well.”

For his part, Montazeri wrote in his memoirs that he equated Khomeini with the shah, whose secret police, SAVAK, was known for its brutal treatment of opponents. “But the crimes of your intelligence [agency] and your prisons make the shah and SAVAK look honorable,” Montazeri wrote in his memoirs.

Speaking on the recently released clip, Montazeri told those responsible for the 1988 massacre of MEK political prisoners that Khomeini would be remembered in history as a “bloodthirsty murderer.”

So how did it all begin?

There are two theories about how the rift between Khomeini and Montazeri began. Mir Hossein Mousavi — once prime minister and now, as leader of the Green Movement, under house arrest — believes the battles began with the execution of Mehdi Hashemi, Montazeri’s son-in-law’s brother. Hashemi was a cleric and senior official of the Revolutionary Guards just after the revolution, but years later he was charged with sedition and murder. He was executed in September 1987. Some believe that he was executed because of his opposition to secret dealings with the United States in what became known as Iran-Contra Affair — when senior officials of Ronald Reagan’s administration sold arms to Iran and sent the proceeds to support the Nicaraguan Contras, a rebel group in opposition to the country’s left-wing government of the time. Khomeini’s son Ahmad had written that Hadi Hashemi, Montazeri’s son-in-law and chief-of-staff, and his brother Mehdi Hashemi schemed to create a rift between the two.

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani has written that Montazeri’s actions were not prudent, that he behaved in haste, and that the issue of his “household” turned into a serious problem. When Mehdi Hashemi was executed, it lit a match that threatened to burn down everything.

At the same time, a second narrative points to disagreements between Montazeri and Khomeini over human rights. Montazeri was against the brutal treatment of opponents and dissidents. His protests started out somewhat low-key and behind the scenes, but with the mass executions of 1988, they intensified. Ultimately, his objections led to him being stripped of his power. This version of events also points to other political disagreements between Khomeini and Montazeri. For example, Montazeri wrote that when the southwestern port city of Khorramshahr was liberated from Iraqi forces on May 24, 1982 he believed Iran “must somehow end the war.” But, much to his intense disappointment, the war dragged on until August 1988.

“In the war Iran...lost so many forces,” Montazeri said on February 12, 1989. “If we have made mistakes...then we must repent.” He made a direct challenge to the ideals and objectives of the war: “Our slogans were wrong,” he said. Less than two weeks later, he received a response. “Our country has succeeded in realizing most of its slogans,” wrote Khomeini. “We are not one bit sorry and repentant about our performance in the war.”

Whatever happened — whether the falling out hinged on the execution of Montazeri’s family member, or on questions of human rights — the outcome was the same: the great allies ended up as bitter enemies.

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani: From Friend to Rival

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani has spoken of his horror when he discovered Khomeini planned to read a letter voicing his anger against Montazeri on Iranian radio on March 26, 1989. “I cried!” he said. He said he warned Khomeini of the potentially dangerous repercussions, and that some people might respond by trying to assassinate Montazeri. Khomeini listened to Rafsanjani and decided not to read the letter to the public. But two days later, Montazeri was removed.

Rafsanjani says that he was not only a close friend of Montazeri but that he was loyal to him as well. “We stood by him till the end,” Rafsanjani wrote about the ordeal. Rafsanjani was, according to senior officials of the time, instrumental in Montazeri being appointed as deputy supreme leader in the summer of 1985, despite opposition from Khomeini. Mohammad Mohammadi Gilani, a high-level cleric who did not approve of Montazeri’s election, said that when he met with Khomeini he learned that Hashemi Rafsanjani and Ahmad Khomeini were the key players in ensuring Montazeri was elected.

Montazeri’s tenure as deputy supreme leader can be divided into two periods. The “normal” period started with his election in 1985 and lasted until September 1987, when Mehdi Hashemi was executed. The second period lasted until March 1989 when Montazeri was removed.

In the second period, Rafsanjani adopted a more critical stance toward Montazeri. After Mehdi Hashemi leaked news of the Iran-Contra Affair, Rafsanjani became disillusioned with Montazeri and his staff. He did not approve of Montazeri’s behavior, and expressed worry about what would happen next.

Mohammadi Reyshahri, who was then Minister of Intelligence, said Rafsanjani had warned him against the possibility that Montazeri might one day become supreme leader. “With the way he acts, tomorrow you might lose your place in the revolution and you might have to live in a foreign country.”

Rafsanjani has largely endorsed Mousavi’s view that the Hashemi affair played a more central role in Montazeri’s downfall. “Mr. Montazeri praised [Mehdi Hashemi] a lot and was very much influenced by him,” wrote Rafsanjani. But despite his worries, he tried to come up with a solution. He suggested to Montazeri that Mehdi Hashemi be given an ambassadorship as a way of removing him from the core of Iranian politics, but Montazeri refused. Even when Montazeri was about to be removed, Rafsanjani says in his memoirs that he was at pains to find a solution, and appealed to Khomeini to think over the matter.

Rafsanjani wrote that he and Ayatollah Khamenei discussed Khomeini’s decision. “We both agreed that that removing him in this way was not prudent. [While we were talking] Ahmad [Khomeini] called and said that Imam had written a harsh letter to Mr. Montazeri,” he said, adding that Khomeini had suggested Rafsanjani and Khamenei take the letter to Montazeri in Qom.

Most probably Rafsanjani believed that Montazeri could be a good political ally — but the Mehdi Hashemi affair changed his mind. This was the end of Rafsanjani’s political relationship with Montazeri. From then on, they were rivals.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: “Vulgar Authority” vs. the “Old Wretch”

Montazeri and Ali Khamenei’s relationship also soured, and of course, Khamenei eventually became Khomeini’s successor. On November 14, 1997 Montazeri said that elevating Khamenei to the position of religious authority had “vulgarized” Shia jurisprudence; 12 days later, Khamenei answered back that the “helpless wretch” Montazeri had stood up against him because his enemies had put him up to it.

Like so many other relationships among Islamic revolutionaries in Iran, Montazeri and Khamenei started on good terms. Montazeri had grown tired of traveling to Tehran to lead prayers and deliver sermons on a very regular basis and wanted to find a replacement. During Friday Prayers in Tehran on January 18, 1980, he introduced Khamenei, who was at the time a resident of Mashhad, to the congregation. “I am one of his devotees,” Montazeri told the crowd. “He is a preacher and I am not.”

During Khamenei’s presidency, their good relations continued, albeit with a measure of ups and downs — for example, Rafsanjani writes in his memoirs that some of Montazeri’s representatives at universities did not meet with the approval of Ayatollah Khamenei. But overall, the relationship was amicable enough. According to Rafsanjani, in 1985 Khamenei supported the election of Montazeri as deputy supreme leader. “Our positions were exactly the same,” he recalled. Even, according to him, in 1988 when Khomeini had ordered a second mass execution of “500 unreligious and communist prisoners,” Khamenei traveled to Qom to ask for Montazeri’s help to stop the executions.

The breaking point came on the day that Khamenei was to become the supreme leader.

Khamenei and Rafsanjani sought the approval of religious authorities. Ayatollah Ebrahim Amini brought a message from Montazeri that said that Montazeri did not support the leadership of Khamenei. Rafsanjani tried to persuade Montazeri to endorse Khamenei, and he succeeded. On June 13, 1989 Montazeri sent a letter confirming his approval, and expressing hope that Khamenei would show appreciation for his endorsement by going public with it, announcing it across Iranian media. But Khamenei ignored his request, and told Rafsanjani that he would not publicize the support — essentially delivering a humiliating blow to Montazeri, although in a somewhat private fashion.

Divisions deepened after Montazeri’s offices were attacked and Montazeri was told that the attackers had the blessing of Ayatollah Khamenei. Then came Montazeri’s announcement that granting religious authority to Khamenei was the “vulgarization” of Shia jurisprudence. In retaliation, Khamenei called him an old “wretch” and a traitor. Montazeri was later placed under house arrest for a period of five years until his death in 2009. Khamenei rejected all entreaties to put an end to the house arrest. He did send a message of condolence to Montazeri’s funeral — but Montazeri’s supporters responded by booing when the message was read out.

Mir Hossein Mousavi and Montazeri: The Alliance that Never Happened

Speaking about the mass executions of 1988, Mir Hossein Mousavi, who was prime minister at the time, has said that he did not have any knowledge of what was going on; nor did Mohammad Reyshahri, who served as Mousavi’s intelligence minister, “utter a word” about them. At any rate, he maintains that Montazeri’s downfall had less to do with the executions and more to do with the execution Mehdi Hashemi. Regardless, the massacre, and how Iran’s most powerful figures reacted to it, had a significant impact on Ayatollah Montazeri’s future, and on his relationship with these figures. In fact, it helped shape the political landscape of Iran today.

Mousavi did not have links to the Mehdi Hashemi scandal either. In both of these key moments, Mousavi was a witness, but not a player. He seemed to agree with Montazeri that the harsh treatment of prisoners was wrong but, when it came to the assessment of Khomeini’s role, the two men differ in opinion. “What happened was not what Imam intended,” Mousavi wrote. “That group of three misconstrued it — and they were wrong.” The three Mousavi refers to are the members of the so-called death panel Khomeini had appointed to carry out executions of political prisoners. The panel comprised of religious legal expert Hossein Ali Nayri, Morteza Ashrafi, then Tehran’s prosecuting attorney, deputy prosecutor Ebrahim Raisi and Mostafa Pourmohamadi, the Ministry of Intelligence's representative to Evin Prison.

During his premiership, Mousavi sided one hundred percent with Ayatollah Khomeini. Khamenei, as president, could not tolerate Mousavi, but Montazeri and Khamenei were at that point on good terms. As a result, Mousavi did not form a particularly friendly relationship with Montazeri. In September 1985, Montazeri sat on the board of intermediaries responsible for solving disagreements between Mousavi and Khamenei over the selection of cabinet ministers, but he was not influential enough to command the wrath of either man.

When Montazeri was stripped of his power, Mousavi ordered all government agencies to remove photographs of Ayatollah Montazeri. Years later, their relationship improved. When Montazeri died in 2009, Mousavi went to the ayatollah’s house in Qom and asked Iranian authorities for a day of national mourning.

Ayatollah Khamenei had put Montazeri under house arrest, and was getting ready to do the same to Mousavi. Now they had a common enemy. But of course it was far too late for them to become political allies.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments