A Supreme Court in Louisiana has ruled that a man accused of raping his wife will be barred from seeing his children until after his trial has concluded, highlighting the lack of clarity that still exists when it comes to sexual crimes and the family, as well as the legal complexities of trying these crimes in court.

The case against New Orleans-based Alireza Sadeghi has attracted local and national US media attention due to both the nature of the crime and the issue of access to the children, who are expected to come forward as witnesses. It’s also a reminder of the taboos that remain when talking about rape, and particularly about rape within marriage.

Sadeghi was initially barred from seeing his three children in line with a 2008 statute that stated that people charged with violent crimes cannot contact their victims, or the victims’ immediate family members.

Marital rape became a crime in federal law in the United States in 1986, but it was not until 1993 that all 50 states passed relevant laws. Prior to this, spouses were excluded from any legal definitions of rape. This stemmed from an English common law that exempt men from prosecution for rape — because sexual consent was simply implied. The exemption, which was set out by Sir Matthew Hale, a Chief Justice of England who ruled on a now-famous case from the 17th century, was removed from the statute books in the United Kingdom in 1991.

In 17 states and the District of Columbia, there are no exemptions from rape prosecution granted to spouses. But in several states, loopholes remain — indicating that rape in marriage is still treated as a lesser crime than other forms of rape. Across the country, a person found guilty of rape must register as a sex offender, but in some jurisdictions, a husband found guilty of raping his wife is not required to register.

Marital Rape in Iran and Elsewhere

According to UN figures, at least 52 countries have laws addressing marital rape.

In Iran, marital rape is not a crime, even if it happens within a forced marriage. Iranian journalists and others have reported on the taboos of talking about any rape in any context in Iran.“Why does my society judge the survivors?” asked one rape survivor who was interviewed. “Why, instead of having support and the space to heal, are we encouraged to remain silent? This silence is what allows these rapes to continue.”

In 2015, CNN reported that, in India, marital rape accounted for 94 per cent of rapes in the country. Although women can file civil cases against their spouses under an anti-domestic violence law passed in 2005, marital rape in India is still legal — and, like in Iran, it’s rarely acknowledged.

Across the African continent, laws on marital rape vary. In Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Kenya,“conjugal rights” are recognized and spousal rape is not a crime. While a law passed in Malawi in 2015 does protect conjugal rights, it stipulates that spouses can refuse sex on “reasonable grounds” — though the definition of these grounds is narrow, and mainly refers to women who have just given birth or who had surgery.

In its global research into women and violence, the World Bank has documented countries that explicitly criminalize marital rape. It is not recognized in several countries in the Middle East, including in Jordan, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. Others, including Bahrain and Qatar, allow cases to be filed against spouses, even though the law does not provide for marital rape specifically. This is the case in a few European countries, too, including Czech Republic and Denmark.

The Sadeghi Case

In early 2015, the wife of Alireza Sadeghi, a plastic surgeon, went to a police officer at New Orleans police station’s Sex Crimes Unit and accused her husband of repeatedly raping her. She later filed a legal complaint against him, leading to Sadeghi’s arrest and indictment. Ahead of the trial, Sadeghi was initially barred from seeing his children under Louisiana law.

But then, on November 15, a district judge ruled the law was unconstitutional and that Sadeghi had a “fundamental liberty interest” to see his children.

The state’s district attorney, advocate groups and legal support services called on the state supreme court to reject the ruling, and, on December 6, in a unanimous decision, the court reinstated the statute.

“This law was put in place specifically to protect children,” says Mary Claire Landry, executive director of the New Orleans Family Justice Center, which had warned of the precedent the ruling might set. “There's been a lot of coverage on and some manipulation of the children in the media. They're being used as pawns,” she says.

Professionals supporting rape survivors warned that reversing this kind of law could have a chilling effect on other rape victims coming forward. “Anytime survivors are let down by a criminal justice system, it can deter others in similar situations from using those same systems and from coming forward,” says rape counselor Amanda Tonkovich.

Following the recent supreme court decision. Sadeghi’s legal counsel, Michael Magner of Jones Walker LLP, said, “We are seeking to have the appeal expedited to the greatest extent possible.” After the judge’s November ruling to allow Sadeghi access to his children, Magner praised the courts, telling The Times-Picayune that the judge had “recognized that Dr. Sadeghi has a fundamental human right in being able to communicate with and raise his children even amidst an ugly divorce.”

But Sadeghi’s wife’s lawyers indicated the defendant had undermined the case in other ways: “In attempting to prove the law was unconstitutional to fathers who shared children with victims of crimes of violence, Sadeghi violated the law by encouraging the victim’s mother to submit an affidavit on his behalf to show he was a good father.”

“The Vindictive Wife”

One of the most powerful legal arguments against marital rape is that of the “vindictive wife” — the assertion that women can pursue false rape charges to secure better divorce settlements. But, writes Jill Elaine Hasday, law professor at the University of Minnesota, “the evidence available from states that allow marital rape prosecutions suggests that the incidents that women report to law enforcement officials tend to be very brutal, and relatively easy to prove.”

Landry from the Family Justice Center says Sadeghi’s legal team also used this argument. They portrayed the plaintiff “as a vindictive wife who's jealous, and who's making this up and is emotionally and mentally disturbed,” she says. Sadeghi also faces other charges, including videotaping his wife and patients without their consent. “This certainly eliminates the perspective that she is a scorned wife and that this is retaliatory,” Landry says.

More Education Needed

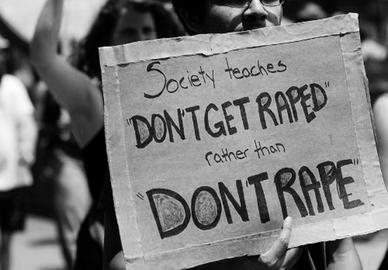

“Our culture is really one that generally does not support survivors,” says counselor Amanda Tonkovich. “It often defends rapists.” She cites the recent case against actor Bill Cosby — and the fact that so many women had to come forward before it was taken seriously — as evidence of a persistent willingness to blame the victim. She says it’s easy to believe the stereotypical image of rape, that of deranged men jumping out from behind bushes. “But we know that most of the time people are raped by someone they know.”

Landry expressed relief over the December 6 supreme court decision in the Sadeghi case, describing it as a “huge victory,” and acknowledging the bravery it takes for women to come forward to “get the justice they deserve.”

But she also recognized the need for better education about rape, and spousal rape. She says it can be difficult to convince juries that spousal rape is a crime. “Most people just really don't believe that. There's a lot of community education that still has to go on.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments