In autumn 1980, just over a year after Iranian revolutionaries overthrew the shah, Ayatollah Khomeini’s new Islamic Republic found itself in a desperate struggle for survival against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

The Iraqi dictator, fearful of what Khomeini’s pan-Islamic agenda would mean for his own authority, and tempted by Iran’s military weakness following purges within its armed forces, invaded the country that September.

Iran was isolated. All of its Arab neighbors, with the exception of Syria, openly or tacitly supported Iraq. Iran’s military, which had hitherto depended mainly on American arms, needed new weapons and equipment.

America, meanwhile, had imposed an arms embargo against Iran ever since pro-Khomeini students had taken US diplomats hostage in 1979. In 1983, the US launched a major diplomatic effort, Operation Staunch, to persuade countries around the world to refuse to sell Iran arms.

Iran’s army ended up depending mainly on Soviet and Chinese-made weapons, many of which it purchased through Soviet-controlled Eastern European countries, Syria, and North Korea. But it still prized US arms highly.

Arms to Rafsanjani—in Secret

By the mid 1980s, some US officials in or close to the administration of President Ronald Reagan—notably National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane and CIA Director William Casey—began to consider the possibility of reaching out to revolutionary “moderates” in Iran in an effort to limit potential Soviet influence. Arms deals, they thought, could provide a sweetener.

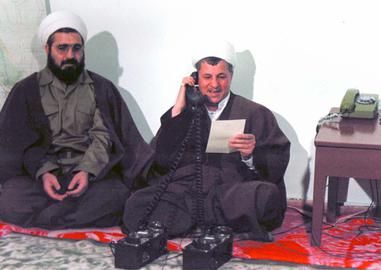

The most prominent person they identified was the late Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a close associate of Khomeini. Members of Reagan’s cabinet likely first noticed him when Hezbollah terrorists hijacked TWA flight 847 from Athens to Rome in June 1985.

“Evidence indicates that McFarlane and Secretary of State George Shultz [who opposed trading arms with Iran] picked up information that Rafsanjani was interested in helping to settle the TWA 847 hijacking,” says Malcolm Byrne of the National Security Archive at George Washington University, author of Iran Contra: Reagan’s Scandal and the Unchecked Abuse of Presidential Power.

“Hezbollah operatives took over the flight, at one point killing American Robert Dean Stethem,” he says. “Rafsanjani directly interceded and helped bring the crisis to a resolution, an outcome more than one senior American took as a strong sign of potential pragmatism and cooperation.”

Iran’s allies in Lebanon, meanwhile—Hezbollah and related factions—had already begun seizing American hostages in that country. Proponents of rapprochement through arms sales hoped that revolutionary “moderates” could be induced to help in exchange for much-needed weaponry.

While it seems paradoxical that a close Khomeini associate able to pull weight with Hezbollah should be identified as a “moderate,” those were the very factors that, for the Americans, made him a likely interlocutor.

“The key point,” says Byrne, “was that he had the approval of Ayatollah Khomeini. Rafsanjani was a powerful figure in his own right, but with Khomeini’s imprimatur, he was able to make use of Iran’s considerable influence on Hezbollah.”

And Rafsanjani, as it happened, was also the main figure conducting Iran’s war effort.

Delivery from the Jewish State!

In August 1985, the US began sending American-made TOW anti-tank missiles to Iran through Israel.

At the time, Byrne says, several senior Iranian officials in Rafsanjani’s circle knew how the arms were being supplied. Among them were Hassan Rouhani, who was then an MP and is now Iran’s president, and Mir Hossein Mousavi, who was then prime minister and is now under house arrest for contesting the results of Iran’s 2009 presidential election.

Further US shipments of TOW missiles and Hawk anti-aircraft missiles to Iran continued into 1986, as Rafsanjani and Iran’s other “moderates” succeeded in securing the release of some of the Americans held in Lebanon.

But in November that year, the sales were exposed, leading to a damaging political scandal in the US. Not only had America sold weapons to Iran illegally, but officials close to Reagan had used the proceeds to pay anti-communist militants in Nicaragua known as the Contras, whom Congress had forbidden the US to fund.

In the US this early, surreptitious effort at rapprochement with Iran led to indictments against the officials involved, and to a major Congressional investigation.

In Iran, it seems, the full facts of the case have never been aired, largely owing to the Israeli connection. “Israel’s role was an especially sensitive topic for the Iranian regime,” Byrne says. “But under conditions of war and facing a chronic shortage of weapons, Rafsanjani and other Iranian officials were apparently willing to brook the connection.”

And Rafsanjani, it seems, even openly acknowledged the presence of Israeli armaments in Iran. “In late 1985,” Byrne says, “a shipment of American-made HAWK missiles taken from Israeli stocks arrived in Iran, reportedly with Israeli markings still on them — the Star of David, which is part of the Israeli Air Force’s insignia.” While the sight of the Israeli hardware had the potential to spoil the nascent US-Iran arms trade, Byrne says, Rafsanjani simply accused unnamed adversaries of using the marked weapons to embarrass him personally.

Risky Business

News of Rafsanjani’s willingness to deal with the US could have destroyed his credentials as a revolutionary. But when his hardline opponents inside Iran named him in connection with the US arms trade, Khomeini came to his defense. “Khomeini fairly swiftly shut down incipient efforts within the Iranian parliament to investigate the scandal,” Byrne says.

After the war ended in 1988, and Rafsanjani became president the following year, he set about pursuing new international relations as part of his reconstruction scheme.

“During the 1990s, according to Hossein Mousavian [Iran’s nuclear negotiator from 2003-2005 and ambassador to Germany from 1990-1997], Rafsanjani hoped to promote a major opening to the West and particularly the United States, mainly through Germany,” Byrne says. Some US officials he adds, say they are unaware of those efforts.

But Rafsanjani’s diplomatic moves during this period, Byrne says along with the persistent allegations of corruption that dogged him in the 2000s defined his political reputation, especially with Iran’s hardliners.

And the circumstances of what Americans came to know as the Iran-Contra affair appear to have stoked mistrust between Iran and the US ever since.

“It set things back significantly,” Byrne says. “On the one hand, it showed the two sides could find common interests and collaborate on that basis, as repugnant as the circumstances were. But on the other hand, the deals were permeated with deception and mistrust. The Iranians relied on a middleman, Manucher Ghorbanifar, who was a notoriously unreliable and self-serving arms merchant who lied to both sides. The Americans also directly misled and lied to their Iranian counterparts, making up a false price list, and providing fake intelligence about Iraq. Then the exposure of the initiative created major political problems domestically for both sides, which could only have raised concerns about the risks of trying again.”

Death of a Dealmaker

Now that Rafsanjani has died, there is no longer an old member of Khomeini’s inner circle in Iran who is likely to act as the patron of future diplomatic initiatives. “He was an influential and consistent proponent of pragmatic relations with the outside world, so his absence is certainly a setback,” Byrne says. But on the other hand, he adds, much now depends on the extent to which Rafsanjani’s successors can build consensus surrounding Iran’s controversial 2015 agreement between Iran, the US, and five other countries over its nuclear program.

“The idea of reaching out diplomatically,” he says, “has moved so far along compared with the 1980s and 1990s, when there was much less of a constituency advocating that kind of approach.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments