Iran’s presidency has been a strange institution ever since it was established a year into Iran’s Islamic Revolution. While Iran’s early presidents were meant to represent the Islamic Republic to the world, they could scarcely compete with the powerful and imposing personality of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who claimed to represent God on earth. Since Khomeini’s death in 1989, Iranian presidents have established themselves as the international face of an ostensibly democratic Iran, but have remained subordinate to the absolute power and socially conservative vision of Khomeini’s successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. And while all of Iran’s presidents have challenged their supreme leader’s powers in some way, most have paid a high political price. Now, ahead of Iran's elections on May 19, IranWire looks back at Iran's past seven presidencies.

***

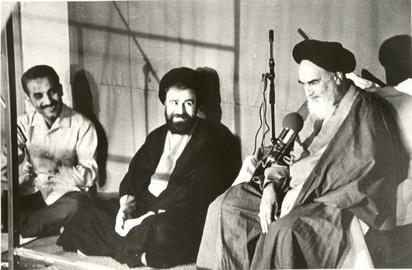

Mohammad-Ali Rajai was president of Iran for less than a month. He took office on August 2nd, 1981 and was killed in a bombing along with Prime Minister Mohammad Javad Banohar and three others on August 30th.

A former math teacher from a humble background—his father had been a shopkeeper in Qazvin—Rajai had served in the air force and was later imprisoned twice for opposing the shah.

A year before he became president, Rajai had been the Islamic Republic’s second prime minister, replacing his some-time political ally Mehdi Bazargan, who had resigned in protest over Ayatollah Khomeini’s refusal to release US embassy staff taken hostage by his supporters.

The question of Bazargan’s replacement resulted in a long standoff between President Abolhassan Banisadr—who was supposed to appoint the new prime minister—and the socially conservative and pro-clerical Islamic Republic Party (IRP), which repeatedly opposed his choices in parliament. Khomeini eventually intervened, forcing Banisadr to appoint Rajai, who was a loyal IRP supporter, as well as a leading figure in the fiercely anti-imperialistic “Islamic left.”

As prime minister, Rajai argued the need for a state-led economy and worked impose an Islamist ideology on Iranian education, banning the teaching of English and closing Iran’s universities to prevent them from becoming centers of opposition to the new regime.

He also participated in negotiations over American hostages. While discussing the hostage situation at the United Nations in October 1980, he famously blamed the US for his arrest by the shah’s secret police and showed the audience his bare right foot, telling them that the Shah’s interrogators had been beaten the soles of his feet and had torn out his toenails.

When the IRP-dominated parliament impeached Banisadr, forcing him to flee the country, it also backed Rajai for president. Once again, Rajai received Khomeini’s blessing.

No More Liberals

“Mohammad Rajai was unconditionally committed to Khomeini's position,” says Mansour Farhang, who served as Iran’s representative to the United Nations before resigning over the hostage crisis. Whereas Banisadr had been a mild critic of Bazargan, he says, Rajai’s presidency marked a decisive break with “liberals” like Bazargan and Banisadr. Rajai and his supporters, Farhang says, had begun using word “liberal” as a synonym for “treacherous” or “pro-American,” a habit they had picked up from Iran’s pro-Moscow communist party, Tudeh.

Rajai was loyal to prominent clerics like Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti and Mohammad-Javad Bahonar, who were both founding members of the IRP. He appointed Bahonar prime minister two days after assuming the presidency. But in the wake of the dispute that led to Banisadr’s impeachment, the presidency was now understood to be a ceremonial role and, unlike Bahonar, Rajai was not an influential in his own right.

Rajai assumed the presidency at a moment of great upheaval. Iran was just one year into its catastrophic war with Iraq, and pro-Khomeini forces were engaged in an armed struggle against rival revolutionary groups, notably the People’s Mujahedin Organization, which had begun carrying out terrorist attacks against the government. Rajai himself had escaped a bombing at the headquarters of the Islamic Republic Party that killed Beheshti, along with 70 other people, most of them government officials, on June 28, 1981.

Following the bombing, Khomeini was more intent than ever on securing clerical dominance in Iran but was apparently still committed to his promise—made under pressure from more secular, nationalist revolutionaries—that clerics should not become president.

The “Man of the People” Who Wasn’t

“Rajai had been trusted by Beheshti and was trusted by Khomeini because he really didn't represent anyone or anything himself,” says historian Ervand Abrahamian. “He was seen as an errand boy for people like Beheshti.”

Given time, Abrahamian says, Rajai’s humble background might have worked for him. “He might have become a ‘man of the people” like Ahmadinejad if he had lived long enough,” Abrahamian says, “but there was a class issue. Many of the other revolutionaries like Banisadr had come from pretty prominent traditional families, and in Iranian politics, that had a positive effect. People didn't take Rajai that seriously.”

Nor did Rajai impress Iran’s newly-named enemies. Gary Sick, who was principal White House aide for Iran under President Jimmy Carter when Rajai became prime minister, saw him as one of Iran’s more inexperienced revolutionaries. “When you have a revolution, in many cases you have a dearth of trained people, and there is a winnowing process,” he says. “You had people who came in who had no idea what government was about but they had a deep belief in the revolution and Khomeini and the idea that God would take care of everything, and that showed. Rajai never made much of a splash.”

On August 30, 1981, a bomb killed Rajai along with Prime Minister Bahonar at the prime minister’s office in Tehran. No one claimed responsibility for the bombing, but the People’s Mujahedin Organization was widely assumed to have carried it out.

Following Rajai’s death, Khomeini abandoned his prohibition on clerics serving as president, and the revolutionary cleric Ali Khamenei succeeded him.

Rajai was the last non-cleric to serve as president until Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took office in 2005. Ahmadinejad himself cited Rajai’s presidency as a model for his own, although many of Rajai’s old allies on the Islamic left—notably former industry minister Behzad Nabavi—had joined the reformist camp in the intervening decades. Following the contested 2009 election, courts sentenced Nabavi to five years in prison for supporting protests in favor of Ahmadinejad’s rival, Mir Hossein Mousavi.

Also in this series:

Banisadr: The Optimistic Islamist (1980-1981)

Khamenei: The Strategic Theocrat (1981-1989)

Rafsanjani: The Architect (1989-1997)

Khatami: The Reformist (1997-2005)

comments