Iran’s presidency has been a strange institution ever since it was established a year into Iran’s Islamic Revolution. While Iran’s early presidents were meant to represent the Islamic Republic to the world, they could scarcely compete with the powerful and imposing personality of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who claimed to represent God on earth. Since Khomeini’s death in 1989, Iranian presidents have established themselves as the international face of an ostensibly democratic Iran, but have remained subordinate to the absolute power and socially conservative vision of Khomeini’s successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. And while all of Iran’s presidents have challenged their supreme leader’s powers in some way, most have paid a high political price. Now, ahead of Iran's elections on May 19, IranWire looks back at Iran's past seven presidencies.

***

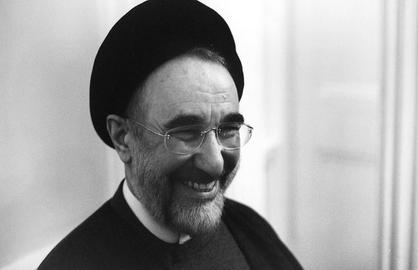

Mohammad Khatami was the Islamic Republic’s first and—many would say—only true reformist president. A former culture minister with a background in philosophy and theology, Khatami received the backing of former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani in Iran’s 1997 presidential elections, in which he scored a substantial win over Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s favored candidate, Ali Akbar Nategh-Nouri. During his two terms in office, Khatami popularized a new political lexicon under the banner reform, which included such ideas as “civil society,” a “dialogue of civilizations,” and “Islamic democracy.” Despite enjoying immense popular support, he never wavered in his loyalty to Khamenei, or to the Islamic political system established by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979.

Khatami was a new type of president. Whereas Rafsanjani had been a businessman and dealmaker concerned with economic liberalization and postwar reconstruction, Khatami encouraged widespread political participation. Within the Islamic establishment, he won support from both Rafsanjani supporters and their sometime rivals on the “Islamic left,” as well as from a generation that had grown up during the repressive years of revolution and war. “Rafsanjani was an important force in not letting the 1997 elections get rigged,” says Nazila Fathi, who covered much of the Khatami era as a correspondent for the New York Times. “The leftists were important in bringing organizational support behind him. But the real vote came from women and the youth, who became politicized in the weeks leading to the elections.”

Curb Your Enthusiasm

Khatami’s landslide election win—he took more than 70 per cent of the vote—along with his popularity among young Iranians, refocused attention on the possibility of conflict between the president and the supreme leader. “Khamenei was always wary of the reform agenda,” says Ali Ansari of the University of St. Andrews, “but he did not react especially during the election because he did not think Khatami would win. What he was most stunned by was Khatami’s sheer popularity. Khamenei has always been jealous of politicians who seem to be more popular than him.”

And while Khatami himself was not about to challenge Khamenei, it was clear that not all of his supporters felt the same way. Many of them would have liked to do away with the position of supreme leader—and in some cases the whole system of Islamic government—altogether. But Khamenei had powerful protectors among the Revolutionary Guards and the judiciary, who soon showed his opponents that there would be hard limits to any reform movement in Iran.

When, a few months after Khatami’s election, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri questioned Khamenei’s authority and religious credentials, he was placed under house arrest. In early 1998, conservatives in parliament pursued the impeachment of Khatami’s interior minister, Abdollah Nouri. Around the same time, the judiciary charged Tehran’s reformist mayor, Gholamhossein Karbaschi, with corruption and sent him to prison. That summer, police began closing pro-Khatami newspapers and arresting their staff.

A Reformist Abroad

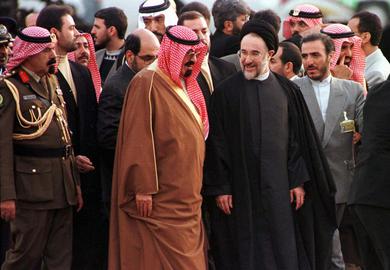

Apart from the relative openness he fostered at home, Khatami also continued Rafsanjani’s efforts to end Iran’s international isolation. In a January 1998 CNN interview, he voiced his respect for “American civilization” and called for a “dialogue of civilizations” with the US. He also moved to improve relations with regional neighbors, notably reaching a cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia. That September, seeking to repair ties with Europe, Khatami sent his foreign minister, Kamal Kharazi, to meet with British officials and resolve the diplomatic break that had resulted from Ayatollah Khomeini’s call for the murder of British author Salman Rushdie nearly ten years earlier.

Michael Axworthy, a historian who headed the Iran section of the British Foreign Office at the time, remembers the impression Khatami made. “He came across as idealistic and academic and slightly otherworldly,” he says. “But his heart was so obviously in the right place that one couldn’t help but want him to succeed.”

While British diplomats had an imperfect understanding of Khatami’s relationship with the supreme leader, Axworthy says, they understood that Khatami had Khamenei’s permission to resolve the matter. “Previously, under Rafsanjani, they had offered formulae like ‘The Iranian government will not send commandos to kill Salman Rushdie.’ I once joked, what’s to prevent them sending a team of house painters or cabaret comedians? Under Khatami, the Iranian government and the British government came up with a formula that was satisfactory.”

Challenging the “Chain Murders”

Back in Iran, some hardened revolutionaries remained unwilling to abandon murder as a political strategy. Since 1979, Iran had carried out numerous extrajudicial killings of perceived enemies of the Islamic system, both inside Iran and abroad. But in 1998, thanks in part to a more open political atmosphere, a series of murders of prominent intellectuals received wide publicity and shocked Iranian society.

Outraged by the killings, a group of writers sent Khamenei and Khatami an open letter demanding action. “The ‘chain murders’ provoked public outcry across the country,” says Ghoncheh Tazmini of the School of Oriental and African Studies, a historian of the Khatami era. “In early 1999, Khatami ordered a full investigation into the murders. Both Khatami and the Supreme Leader condemned the crimes, and Khamenei called them ‘criminal, ugly and hateful.’”

Although the murders were eventually attributed to “rogue elements” within Iran’s intelligence ministry, and Khamenei blamed unnamed foreign enemies for the crimes, what mattered was that he did not defend them. His reaction, Tazmini says, was a clear sign to his supporters that such attacks against dissidents were unacceptable. Khamenei even publicly thanked Khatami and the investigative committee for pursuing the case.

The Other Khatami

While Khamenei appears to have accepted Khatami’s efforts to curb the regime’s most extreme excesses, Khatami would also have to curb his supporters’ more radical hopes. When, in the spring and summer of 1999, pro-Khatami students took to the streets to protest the arrests of student leaders along with new laws restricting the reformist press, they made clear that Khamenei was their target. “The anger was aimed at Khamenei,” says Fathi, who saw the protests up close. “The slogans were all about him. They called for his fall, they called him a dictator, a tyrant, everything.”

Khatami denounced his own supporters. “He came out and spoke very awkwardly about the protests and said the students were causing riots and instability,” Fathi says. “He was a totally different person.” Khatami and Khamenei maintained cordial personal relations and met regularly to discuss politics. It was clear that Khamenei had communicated what he now expected of the president. “A lot of people said Khatami could have been more forceful, and could eventually have abolished the position of supreme leader,” Fathi says. “But people close to Khamenei say that Khamenei and the Guards would have gone very far to prevent that. Khatami didn't believe that bloodshed would help the country.”

An Iranian Gorbachev?

In 2000, reformists won a majority in parliament, though they did so in the face of mounting opposition from pro-Khamenei factions, including the conservative-dominated Guardian Council, which blocked many reform bills, and the judiciary, which intimidated and arrested reformists, journalists, women’s activists, and other freethinkers. While the reformist parliament did make some gains, particularly in the realm of women’s rights, it faced increasing deadlock.

Enthusiasm for Khatami abroad, meanwhile, alarmed Khamenei, who was always quick to warn of both foreign interference and “illusions fostered abroad.” One such illusion, as far as he was concerned, was that Khatami was an Iranian Gorbachev and that the Islamic Republic could collapse like the Soviet Union. In a 2000 speech, he challenged those making the comparison:

Their first mistake is that Mr. Khatami is not Gorbachev. Their second mistake is that Islam is not communism. Their next mistake is that the popular system of Islamic Republic is not the dictatorial regime of the proletariat. The fourth mistake is that the integrated Iran is not like the former Soviet Union, which was made up of different republics. And their next mistake is that they have underrated the pivotal role of the religious and spiritual leadership in Iran.

In other words, Khamenei and Iran’s Islamic system were popular, whereas communism was not. Khatami, for his part, proved popular enough to win a second term in 2001, although it was in many ways ill-fated. He faced continued political obstruction inside Iran, and US President George W. Bush’s 2002 “Axis of Evil” speech—which identified Iran as a repressive state seeking weapons of mass destruction—allowed Khatami’s rivals to portray his diplomacy as fruitless.

Today, Khatami’s legacy is perhaps the most debated of any Iranian president. Many of those debates center on how much change Khatami actually wanted. “It must be noted that Khatami wanted to reform the system in order to save it,” Tazmini says. “Khatami, the symbol of reform, wanted to upgrade the system in line with contemporary needs and to fashion a fully-fledged ‘religious democracy.’ As the custodian of the revolution, Khamenei was more cautious about reform initiatives. Both shared a distaste for violent protests.”

For many Iranians, Khatami was more potent as a symbol of the country’s potential than as a political actor. “He was not a politician,” Fathi says. “He was a philosopher. He spoke nicely, he said the right things, and he changed the political discourse. Look at what presidential candidates are saying during the 2017 election campaign. It's all based on the conversation he started. Before Khatami, nobody talked about people's rights or civil society. Nobody had any rights, and it was all about the Islamic Republic and revolutionary values.”

Also in this series:

Banisadr: The Optimistic Islamist (1980-1981)

Rajai: The Clerics’ Loyalist (1981)

Khamenei: The Strategic Theocrat (1981-1989)

Rafsanjani: The Architect (1989-1997)

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments