Iran’s presidency has been a strange institution ever since it was established a year into Iran’s Islamic Revolution. While Iran’s early presidents were meant to represent the Islamic Republic to the world, they could scarcely compete with the powerful and imposing personality of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who claimed to represent God on earth. Since Khomeini’s death in 1989, Iranian presidents have established themselves as the international face of an ostensibly democratic Iran, but have remained subordinate to the absolute power and socially conservative vision of Khomeini’s successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. And while all of Iran’s presidents have challenged their supreme leader’s powers in some way, most have paid a high political price. Now, ahead of Iran's elections on May 19, IranWire looks back at Iran's past seven presidencies.

***

In 2005, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became the first non-cleric to serve as Iran’s president since Mohammad Ali Rajai, who had been assassinated in 1981. A former teacher and engineer who had been the governor of Ardabil Province from 1993 to 1997 and mayor of Tehran since 2003, Ahmadinejad’s success in the race against Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani—a powerful cleric widely regarded as the architect of Iran’s system of Islamic government—took observers by surprise. While Ahmadinejad likely benefitted from a degree of voter apathy following the stagnant second term of the reformist cleric Mohammad Khatami, he also succeeded in portraying Rafsanjani as the godfather of a corrupt elite.

“What really struck me about the 2005 election campaign,” says Roberto Toscano, who was Italy’s ambassador to Iran from 2003 to 2008, “was a TV show I saw about the candidates. They sent a TV crew to the mayor’s office, but somebody answered, ‘He doesn’t live here.’” The TV crew, he says, was sent to a modest apartment in a poor neighborhood in southern Tehran, where they found Ahmadinejad having tea with an old lady. “You know what? It was not made up. The guy was really like that. That gained him millions of votes.”

Toscano, who had met Ahmadinejad when he had accompanied a delegation from Rome to the mayor’s office offering garbage trucks for sale, had been less impressed. “He was not very articulate, and he wasn’t really relating to anybody. Later, when he announced he was running for president, I made the same mistake as many of my Iranian friends. I said, ‘Who, that guy?’ The real mistake people made was to underestimate the appeal of anti-establishment figures, people who look like everyone else and claim to represent the common people. It explains 2005, and it explains events happening all over the world today.”

Robin Hood of the Revolutionary Guards

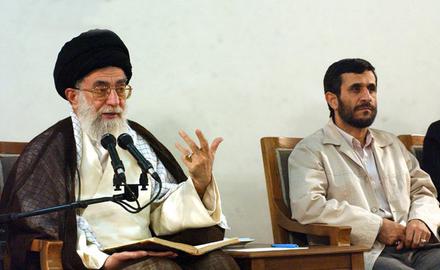

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei had his own reasons to favor a seemingly obscure populist. Khamenei’s one-time ally Rafsanjani had already become a rival operating within numerous powerful offices including the Assembly of Experts and the Expediency Council. As fellow founder of the Islamic Republic, Rafsanjani would have been seen as an equal to Khamenei, not a subordinate. Ahmadinejad had close ties to Iran’s powerful security forces, including Khamenei’s chief supporters and defenders, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps. With oil prices rising, it suited Khamenei to have a president who would spend that wealth in a manner that would shore up his power.

During his first term, Ahmadinejad’s agenda was largely economic. He focused on distributing Iran’s oil wealth, doling out marriage and housing assistance to poor, conservative religious communities that could be counted on to support him in the future. He also directed big government-funded projects to the Revolutionary Guards, a political-military organization whose ever-growing role in Iran’s economy has been a constant source alarm and annoyance to Iran’s reformists. As a loyal servant of Khamenei, Ahmadinejad was also willing to take the hit for unpopular policies, like reducing energy subsidies—something Khatami and the reformists had been unwilling to do.

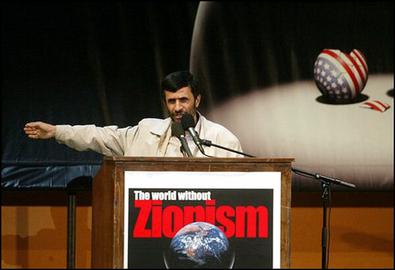

In the international sphere, Ahmadinejad amplified the supreme leader’s prejudices for the whole world. Speaking at Iran’s “World Without Zionism” event in October 2005, he called for Israel to be wiped off the map—a statement that, in light of growing international concern over Iran’s nuclear program, caused great alarm in Israel, and amongst its allies. Speaking in December 2005 on Iranian state television, Ahmadinejad called the Holocaust a “myth” that westerners had elevated “above God, religion, and the prophets.”

These statements, says Nazila Fathi, who covered Ahmadinejad’s first term for the New York Times, were nothing new for the Islamic Republic. Ahmadinejad, she says, was really just paraphrasing Khamenei’s predecessor, Ayatollah Khomeini. But Ahmadinejad clearly relished the outrage. “It got a lot of attention and then he kept repeating it,” she says. “For him, even bad attention was good publicity.”

The Unpopular Populist

Iran’s 2009 presidential election resulted in the worst political crisis the Islamic Republic has ever faced. Ahmadinejad’s main opponents were former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi (a long-time Khamenei rival) and former speaker of Parliament Mehdi Karroubi. Mousavi’s campaign, in particular, gained substantial support from young reformists who, in the weeks ahead of elections, filled the streets dressed in green to show their support for Mousavi’s promises of greater social freedoms. On June 12th, voters turned out in record numbers, but many of them reported irregularities at polling stations. When Ahmadinejad won, Mousavi and Karroubi supporters claimed the election had been rigged.

The following day, thousands of protesters filled the streets of Tehran chanting, “Where is My Vote?” As protests mounted—with hundreds of thousands of Mousavi supporters gathering in Tehran’s Azadi Square on June 15—Khamenei moved quickly to support Ahmadinejad. Speaking in a Friday sermon on the 19th, he endorsed the election result and denounced the protests. “Flexing muscles on the streets after the election is not right,” Khamenei said. “It means challenging the elections and democracy. If they don’t stop, the consequences of the chaos would be their responsibility.” He also warned Mousavi and Karroubi that if protests continued, they would be “responsible for bloodshed.” Ahmadinejad compared the protesters to supporters of a losing soccer team and insulted them. "The nation's huge river,” he said, “would not leave any opportunity for the expression of dirt and dust.”

The protests did not abate. Mousavi and Karroubi’s supporters pressured them to challenge the legitimacy of the election and fight for greater political freedom. The “Green Movement” protesters, as they became known, grew ever bolder in their slogans, calling Khamenei a dictator. Security forces called the movement a “sedition” backed by foreign powers, and cracked down hard on protests, beating people in the streets, arresting hundreds, and causing several deaths. Protests continued into 2010. In February 2011, as “Arab Spring” demonstrations took hold in Tunisia and Egypt, Mousavi and Karroubi, called for demonstrations in solidarity with the Arab protestors. Iran’s security forces retaliated by arresting both men, and have held them under house arrest, without trial, ever since.

Khamenei’s Bad Investment

Following the 2009 elections, Khamenei had put the full weight of Iran’s security forces behind Ahmadinejad. But Ahmadinejad seems to have been more embarrassed than grateful. Ahmadinejad, Fathi says, may not have wanted to be seen as the face of political repression in Iran. “Within the first year and a half after the second term, there were huge disagreements between Ahmadinejad and the Revolutionary Guards over how to deal with the Green Movement,” she says. “Ahmadinejad didn’t want to go as far as the Guards were going. There were reports about his meetings with the Guards commanders, and how he said he didn’t want to go as far as getting protesters killed in custody because he would get blamed for it.”

Then came a succession of standoffs between Ahmadinejad and Khamenei over Ahmadinejad’s political selections, notably his appointment in July 2009 of his long-time friend Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei as first vice president. Mashaei had irritated Iran’s clerics with his Iranian nationalism, his unorthodox opinions on Islam, and his perplexing statement that Iranians were “friends of all people in the world—even Israelis.” When Khamenei forced Mashaei to resign, Ahmadinejad retaliated by firing Intelligence Minister Gholam-Hossein Mohsen-Ejei, who had opposed the appointment. In 2011, Ahmadinejad fired another intelligence minister, Heydar Moslehi, but Khamenei immediately reinstated him. That time, Ahmadinejad retaliated with an 11-day walkout.

“If any president shook things up in a way nobody expected, it was Ahmadinejad,” says Alex Vatanka of the Middle East Institute. “Nobody would expect that from the political angle he came from, but he was a rebel. People were saying to him, ‘Khamenei has asked you to show up, and the fact that you don’t show up is a slap in his face. Can you see the implications of this acrimony and disobedience?’ According to some accounts, he replied, ‘I get my orders from the 12th Imam, the messiah.’” In other words, Ahmadinejad was challenging the Islamic Republic’s whole conception of Islamic rule, known as the velayat-e faqih, whereby Iran’s supreme leader claims to govern on behalf of a “hidden” holy figure expected to return to Earth at the end of time.

To a political establishment whose main objective is to survive, this was a stunning act of subversion. “He probably didn’t know the profound implications of what he was messing around with,” Vatanka says, “but it was a challenge to the entire Shia political establishment. It’s like going from being a fanatical Catholic to being a fanatical Protestant or even a Calvinist, saying that human beings don’t need the clergy because they can have a direct relationship with God.” Ahmadinejad’s enemies branded him and Mashaei, now his chief of staff, as members of a “deviant current” dabbling in black magic.

In 2012, Ahmadinejad became the first president in Islamic Republic history to be summoned by parliament to answer questions concerning his controversial behavior, and—in an atmosphere of escalating international sanctions over Iran’s nuclear program—his handling of the economy. Ahmadinejad, apparently at risk of becoming the first president since Abolhossein Banisadr to be impeached, simply laughed off the MPs’ questions, and even taunted them for not coming up with better ones.

But since Khamenei had once supported Ahmadinejad so vocally—he had even, in the early days, that Ahmadinejad’s view were closer to his own than those of fellow Islamic Republic Founder Rafsanjani—it was simpler from a face-saving point of view to let him finish out his term. Whereas other presidents had challenged supreme leaders over civil liberties, social freedoms and the constitutional division of power, Ahmadinejad, a little man from nowhere, had hacked at the very root of the Islamic Republic and laughed.

Also in this series:

Banisadr: The Optimistic Islamist (1980-1981)

Rajai: The Clerics’ Loyalist (1981)

Khamenei: The Strategic Theocrat (1981-1989)

Rafsanjani: The Architect (1989-1997)

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments