After a short-lived stint as deputy head of Iran’s Environmental Protection Agency, Kaveh Madani, who had previously worked and taught in the United States and the United Kingdom, has decided to leave Iran.

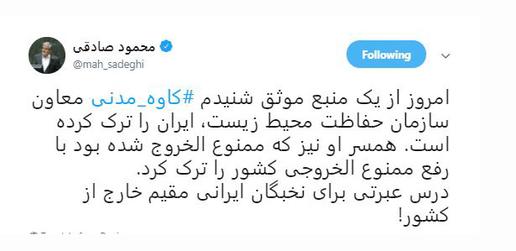

The news follows the arrest of Madani and other environmentalists in February, after which Madani spent a brief time in custody. . Mahmood Sadeghi, a reformist member of parliament from Tehran, publicized Madani’s decision on Twitter, where he also revealed that the travel ban on Madani’s wife had been lifted and she had left Iran as well. “This should teach a lesson to Iranian elites living outside Iran,” he wrote.

The website Ensaf News reported that Madani was in Thailand for a conference about environmental issues when he submitted his resignation, which officials accepted. [Persian link].

In his first tweet after resigning, Madani quoted a poem by the Iranian contemporary poet Houshang Ebtehaj: “Sore are my feet and short is my breath, but I departed the way I wanted.”

Madani was born in Tehran in 1981 to parents working in the water sector. Like many bright Iranians of his generation, he left the country after getting his Bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from the prestigious University of Tabriz in Turkic-speaking northwestern Iran. After university, his life resembled that of many young and educated Iranians and he spent a considerable amount of time outside the country. He studied for a Master’s degree in water resources at Lund University in Sweden and then for a PhD in civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Davis, which he completed in 2009.

In 2012, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) presented Madani with an award for “representing the bold and humanitarian future of civil engineering.” The European Geosciences Union awarded him a similar accolade, and, in 2017, he was awarded the ASCE’s Water L. Huber prize, the most prestigious award for mid-career engineers.

Before being appointed in September 2017 as deputy head of Iran’s Environmental Protection Agency, where he was put in charge of running the government department’s education and research section, Madani taught systems analysis and policy at London’s Imperial College for four years. His appointment to the government agency was welcomed by both Iran’s media and the country’s scientific community.

The Plain-Talking Scientist

While he worked outside Iran, Madani kept in touch with his homeland. He traveled home regularly, sometimes to lecture at Tehran’s well-regarded Khajeh Nasir Tousi University of Technology (KNTU), named after the 13th-century Persian polymath. He soon attracted the attention of Iranian journalists, consistently on the look-out for the success of fellow Iranians abroad. He emerged as a frequent commentator on the grave environmental crises Iran faced. Speaking in a straightforward, accessible way, he established a firm online presence and used catchy phrases like “water bankruptcy” instead of the more commonly used “water crisis.”

His fame also grew outside Iran as well. When journalist Gelareh Darabi made an Al-Jazeera documentary about Iran’s water crisis, Madani became the film’s star attraction. Speaking in a well-articulated English, he accompanied the director to the city of Isfahan, where the famous river Zayandeh Rood is a testament to the country's crisis and has for years been almost completely dry. In the film, Madani tells Darabi that the river’s problems are a “symbol of what’s happening on the national scale” and suggests that population growth, inefficient agriculture practices and mismanagement were the “three main causes” of the crisis. The young, plain-talking scientist was also featured on a BBC World documentary on dust storms in the Middle East.

The Rouhani administration had promised to give top jobs to innovative, forward-looking professionals, and not necessarily restrict itself to hiring people who had done well within Iran’s political establishment. The government took note of Madani’s record, and his approach to his work. In February 2017, Madani was invited to head Iran’s first international climate change conference. A few months later, Rouhani was re-elected and pledged to continue his modernizing agenda. Although several environmental NGOs had pushed for Madani to be made the minister of energy, when Rouhani announced his cabinet, Madani was not part of it.

High Expectations

But then came the surprise appointment in September 2017. Madani packed his bags to come to Tehran and serve a government that pledges good governance but faces the high expectations of a wary population.

“There are a lot of people abroad, waiting and watching closely to see what’s going to happen,” Madani told Tehran’s English-language daily the Tehran Times. “If I succeed, we might see more people coming back to help the government.”

He was too much of an optimist. In an interview with the newspaper Shargh after his appointment, he said that his parents had been against him moving to Iran, as were many Iranian expatriates on social media. “They all said that it was ‘elite-killing’,” said Madani, “meaning that they would bring a man of science into an executive position and then destroy him.” Such words seemed too pessimistic at the time, but they proved prescient when Madani was arrested.

Intelligence agents from the Revolutionary Guards arrested Madani on Sunday, February 11. He was released a day later but apparently remained under surveillance.

After being arrested, Madani was taken to an unknown location. According to an IranWire source, on Monday, February 12, Madani, accompanied by a number of security agents, returned to his office and, in the presence of the agents, he recorded a video and posted it on Instagram. The same day, security agents confiscated documents from his office.

The source told IranWire that the Revolutionary Guards’ agents also “respectfully” questioned some of Madani’s colleagues about his activities. After returning to his office, the source said, signs of fear could clearly be seen on Madani’s face.

The Environmentalist “Espionage Ring”

But Madani’s arrest was connected to a bigger case. Prior to his trouble, several environmentalists had been arrested on accusations of spying. Those arrested were activists and managers with links to the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation (PWHF) an NGO known for its efforts to save the Asiatic cheetah, an endangered species.

On February 11, Tehran’s Prosecutor Abbas Jafari Dowlatabadi confirmed authorities had carried out arrests in connection with a “spying case.” He said that the accused had been acting under orders from CIA and Mossad intelligence officers to infiltrate the Iranian scientific community and gather information about sensitive military sites, including missile installations. He claimed that some of the arrested had confessed that they had visited “occupied territories” repeatedly, including one visit to participate in a conference in which Mossad agents were present.

Gholamhossein Esmaili, the head of Tehran province’s judiciary, said the environmentalists “were gathering information and supplying it to foreigners.” And on February 11, he warned there could be further arrests.

Kavous Seyed-Emami, a trustee of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation, was arrested on January 24. On February 9, authorities notified his family that he had committed suicide in Evin Prison. On February 11, Jafari Dowlatabadi claimed that Seyed-Emami had confessed against himself before taking his own life. Speaking at a gathering commemorating the 39th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution, Jafari Dolatabadi added: “There were many confessions against this individual and he confessed against himself as well, and unfortunately he committed suicide.” The news was met by widespread disbelief and shock.

It is not clear what, if any, connections Kaveh Madani had with Seyed-Emami and the other arrested environmentalists.

By mid-march, Madani’s life regained some normalcy and he resumed his interactions with the Iranian media, albeit in a much more toned-down manner. But then, on March 31, principlist media published photographs of a party and accused Madani of dancing and debauchery — behavior they claimed was not appropriate for an official of the Islamic Republic. However, the photographs were not recent, and they were not taken in Iran. They were taken in 2013 at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco, California.

It is likely that the publication of these pictures was part of a campaign launched by security agencies hostile to him. In any case, the photos, and the death of Kavous Seyed-Emami in prison, were apparently enough to convince Kaveh Madani that he better leave before it was too late.

Madani is the latest victim of Iranian authorities’ hostility toward educated Iranian expatriates, many of whom hope to return to Iran to do good. He was not the first, nor will he be the last.

More on the persecution of environmentalists in Iran:

Kaveh Madani Remains Under Surveillance, February 2018

Scientist Arrested Four Months after Returning to Iran, February 2018

Son Calls for Independent Investigation into “Suicide”, February 2018

News of Iranian-Canadian's "Suicide" in Prison Shocks Iran, February 2018

The “Suicide” Project: A Warning to Activists, February 2018

Can a 36-year-old Scientist Solve Iran’s Water Crisis?, December 2017

comments