The labor activist Reza Shahabi was behind bars when his wife Robabeh Rezaei came up with the idea of setting up a little shop to sell homemade food items. With her husband in prison, the family had practically no income and she had to take care of expenses large and small, plus provide for their two children in college.

Reza Shahabi, a 45-year-old bus driver and trade unionist, was the treasurer of the Union of the Workers of Tehran Unified Bus Company when he was arrested on June 12, 2010 and charged with “propaganda against the regime” and “gathering and collusion with the aim of committing acts against national security.” Since then he has been in and out of detention, prison and the courtroom. In April 2012, the Revolutionary Court Judge Abolghasem Salavati, notorious for violating the rights of defendants, sentenced him to six years in prison and banned him from public activity for five years.

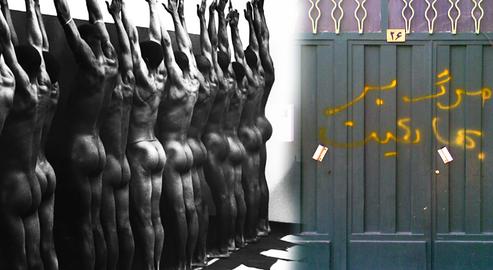

Shahabi was badly beaten and suffered physical damages, prompting Amnesty International to raise international awareness about his case and declare him a prisoner of conscience. “Doctors told him after an MRI that some of the vertebra in his neck have deteriorated and are in need of surgery followed by six months of complete rest, otherwise his left side could become paralyzed,” Amnesty said. “Reportedly, his back and spinal cord were damaged as a result of heavy beatings he received following his arrest.”

With her husband in prison, Robabeh Rezaei set up their shop, which she called Shahabi after her husband, offering homemade ingredients used in Iranian cuisine as well as some simple prepared dishes. Workers, civil rights activists and unionists also tried to help by patronizing the shop whenever they could and they were complimentary about the quality of the products as well. But Robabeh was not only thinking about the income. She also wanted to make a good name for her husband, and when the ailing Shahabi was granted medical leave in September 2014, he helped her and they somehow managed to make a living.

But nearly three years later he was informed that the time he had spent outside the prison on medical furlough was not counted as time served and that he would have to return to prison. He returned on August 8, 2017. This time the shop was forced to close its doors because of high rent, water and electricity bills and other expenses.

A year on, Shahabi has been released again and says he is happy he does not have to face another case against him. “Thank God, I have no new case and with the help of Robabeh I want to resume making food products at home.” For Shahabi, trying to stay on his feet, both literally and figuratively, is a form of civil resistance to pressures from the government.

“We had rented a shop but when they threw me in jail again the rent had gone up and my wife could not single-handedly manage to pay the rent and other expenses,” Shahabi says. “So she left the shop and continued her work at home. After my release and dealing with the maladies that I suffered in prison, I tried to return to my old job but they would not allow it. So, in order to survive and to pay all these expenses — some normal and some forced on us for medical treatment — we decided to resume making food at home.”

According to Shahabi, in the current climate, it is impossible for working people to afford the down payment needed to rent a shop. “You have to pay an advance of at least 100 million tomans [close to $24,000] and a monthly rent of two to four million tomans [around $480-960],” he says, “and this is besides water and electricity bills and side expenses. We decided to continue making our products and try to market them through friends, unionists, social activists and Telegram channels.”

Their little home-based business is, for him, a type of peaceful resistance. “In recent years,” says Shahabi, “the regime has tried to close all doors to political prisoners, dissenters and their families. But fighting can be done in many shapes and forms — from defending labor rights to enlightening people. They want to bring me, a laborer, and my family, to our knees. I want to send a message to workers who are afraid to step forward because they might lose their jobs or go to prison that there are many ways in life to fight — and a fighting human being cannot give in to despair.”

Shahabi believes that even by setting up small businesses individuals can get people’s support and, in turn, help people who are in even worse dire straits. “We were able to show that you can protest even by selling pickles,” he says. “We tried to give hope to those who are fearful of pushing on. I myself was helped by some of my friends to get ingredients and other things.”

I ask Reza Shahabi if he’s sure there are no further cases against him still waiting to be resolved. He laughs and says that, fortunately, for now his luck is holding. But then he adds: “They counted the 968 days of my medical furlough as an ‘absence.’” Authorities told him that they had agreed on the medical leave, but that instead of spending time on getting treatment, he had been active in union issues and had continued to protest. They demanded to know why he was attending union meetings and then returned him to prison to serve the time that he “owed” because of his medical leave.

“I had practically served my time,” Shahabi says. “When I was rearrested I immediately went on a hunger strike. After protests by my family, by my colleagues at the Unified Bus Company and by other sympathetic groups, eventually two days before Norooz [March 21, 2018], they consolidated my sentences based on the Islamic Penal Code and I was released [on March 19] by a ruling from Branch 36 of the appeals court. But now I have been banned for two years from civil and union activities, journalism and even online activities.”

Shahabi still carries the deep physical scars of prison. “I am not the same man that I was before prison,” he says. “My health is not that great. I have had serious surgeries on my neck and my back that required a prosthesis. It is only natural that now getting ingredients and preparing food items puts a lot of pressure on my body. My wife is always on my side. But it happens a lot that my feet or the left side of my face lose sense or my blood pressure shoots up, my eyes close and my physical condition gets topsy-turvy. Altogether my health is not good but, well, this is a gift from prison. Fighting has costs. Many lose hope after prison, but I am happy that I still have my ideals and my hope in tomorrow.”

More on Reza Shahabi and his colleagues:

Tehran Bus Drivers Did Not Forget Their Imprisoned Colleague, September 15, 2017

Tehran Bus Drivers Beaten up During Protests, December 9, 2016

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments