Passers-by see her every day, a woman of around 40 who crouches on a corner of Rastakhiz Avenue in Karaj’s Gohardasht area, holding a canvas bag and a threadbare blanket.

She does not look like an addict, or even somebody with a hangover. But her face shows that she has seen better times. A skinny teen of around 15, pale and listless, leans on the woman. A deep pain is visible in his eyes, as if he is waiting for a miracle to end the pain. There is not even one strand of hair on his head, and he has no eyebrows or eyelashes either.

“I am not a beggar,” says a cardboard sign set out in front of the woman. “Please do not drop coins here. I am waiting for a customer. I will sell my kidney to save my son’s life.”

A passerby wants to film her on a mobile phone. “Please do not video me,” she tells him. “What is pleasant about other people’s unhappiness that you want to share? Please don’t.”

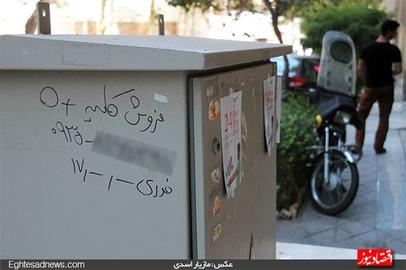

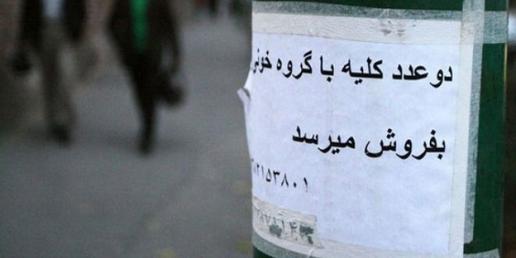

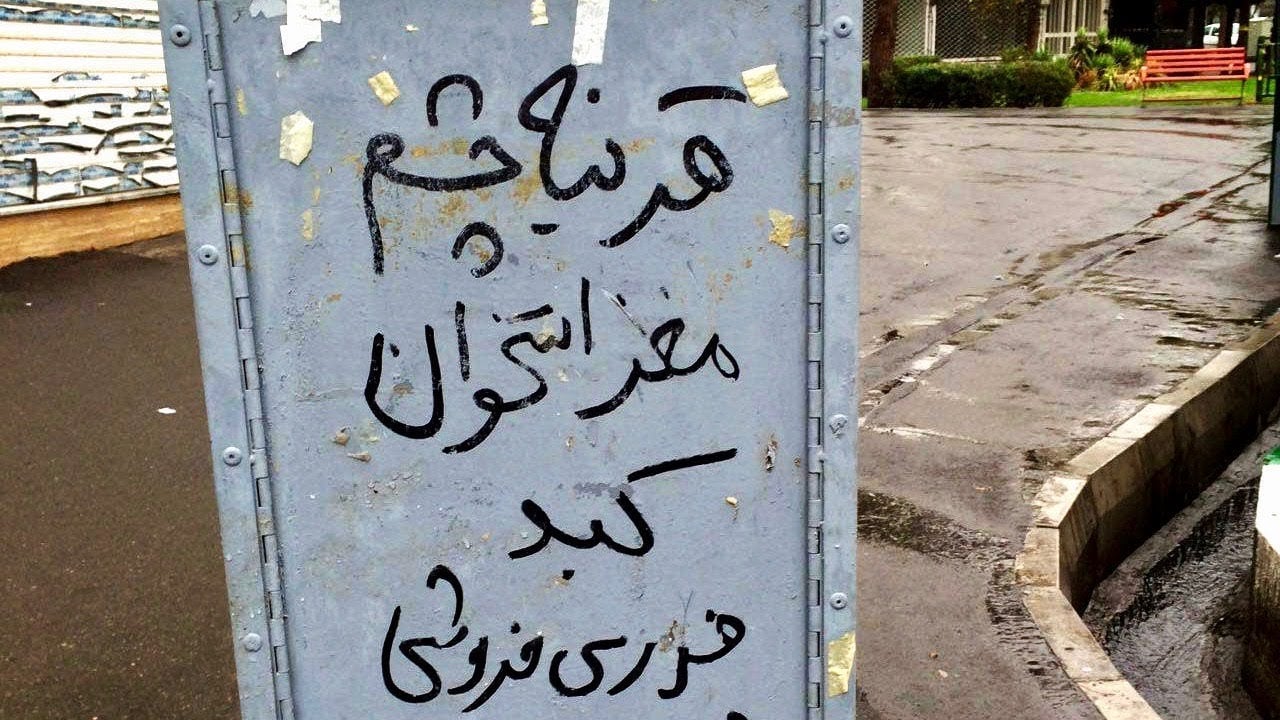

People working in the organ trade regularly use social media as a marketing tool. Most of the websites targeting the trade are reminiscent of a butcher’s shop more than anything else, but of course the difference is that they are trading human parts — from a kidney or part of the liver to a cornea, bone marrow and even newborn babies.

Next to the offers posted on these pages are the desperate stories of people inflicted by the various manifestations of abject poverty: Bounced checks, hunger, dowry payments, paying for “blood money” so that a loved one can leave prison, curing a sister, a mother, a daughter or a son, saving a father from debt. And the list goes on.

First Loan Sharks, then Kidney Traders

One young woman posts that she is willing to sell a kidney for 15 million tomans, or close to $3,600 at the national bank’s official price. She also offers up a cornea, bone marrow and a good chunk of her liver for sale.

She, her two sisters and her mother live in a shack near the village of Amir Abad in the province of Khuzestan. They are far away from a shop or any other amenities. They have no running water or indoor toilet and their mother cooks for them on an old portable gas stove. Then she takes out the dishes to wash them in a nearby pit — that is, if she can find much fetid water left after this year’s drought.

“My father has been in Karun Prison in Ahvaz for the past six years,” she says. “We had a home in the village of Ahmad Agha in Izeh. It was an adobe house but we were together and this made us happy. My father worked for an orchard owner close by, but then came the drought, the orchard dried up and my father lost his job. At first he borrowed money but little by little he could not afford even to buy us food. He was forced to borrow a little money from a loan shark in Izeh but he was not able to repay even that little bit. He started to borrow more money to pay his debts and eventually ended up in prison. We lost our home in Ahmad Agha so we went a few kilometers outside Amir Abad village and made a shack with tin plates. Every night we go to sleep in fear because the walls and the door are flimsy. We don’t have a bathroom or a toilet.”

“Miss!” she begs me, “can you do something so that somebody will buy my kidney? I am healthy. My kidney is of better quality than those others on the site because I am still young. I am not yet 18 and have the ID to prove it. I will bring it to you wherever you want and show it to you. With the money I make I can get my father out of prison. And, besides the kidney I will sell anything else that people want to buy. I would sell one of my eyes. I would survive with one kidney and one eye. But, as things are, my sisters and my mother and I will die in the middle of nowhere. The cold season is around the corner. With the first rains we are going to die under the tin roof.”

Enter the Middleman

Under Iranian law, buying or selling body organs is illegal. And yet the online market is booming and nobody is lifting a finger to stop it. The middlemen are always busy making financial arrangements with people who control social media profiles or commercial websites. The sites use different methods to attract customers or middlemen and beat the competition. They often present profiles of people offering their body parts for sale, posting information about their age, blood group and physical test results. Website owners get a considerable amount of money to publish an ad, both for buying and selling. And, of course, some of the money goes to these middlemen.

But the trade of human organs is not only promoted online. As with the stories of the woman with the sick son and the young woman afraid of the winter rains, people who are desperate to sell accost people at traffic lights, in the middle of boulevards and especially outside the hospitals.

Market prices vary and fluctuate. There is more demand for organs from donors with less common blood types. Some sellers even have a blood test beforehand as a way to attract customers. A twisted game ensues between buyer and seller. In the course of bargaining on the phone, sellers might drop their prices by one-third, and even to one-tenth of the original price, if prospective buyers show reluctance to agree to the price. At the same time, these sellers do everything they can to continue the bargaining process as long as possible.

No Longer a Rare Sight

When the traffic light turns red, a 20-something-year-old man jumps out and starts wiping windshields with a rag. A rubber band hangs from around his neck, and the sign attached to it advertises a kidney for sale. But the passersby pay no attention to him, and no driver lowers his or her car window to ask him why he is a selling a part of his body. In fact, ads buying or selling body parts are no longer something new and nobody finds them unusual anymore.

Kobra, 27, has listed her phone number under an ad to sell a kidney, which is attached to the wall of the dialysis ward of a hospital in Ahvaz, the capital of Khuzestan province. “My six-year old child is going to school this September,” she told IranWire. “But I have no money to pay for the basic necessities like clothes, stationary or a schoolbag.” She also wants to use the rest of the proceeds from the sale of her kidney to fix the collapsed wall of their humble home in the wilderness outside Ahvaz. The house has only one room of 42 square meters and is located 20 kilometers from Ahvaz.

Getting a Cut from the Proceeds

“I don’t know what godless individual took a picture of the ad,” says Kobra. “They call me all the time. They even called me from the Society for the Support of Kidney Patients. I guess they want their cut. Here, everybody wants his own cut. Nobody takes pity on anybody else. They must be unhappy because I want to sell a part of my body without involving them. I have to send my child to school. I have to fix our wall. My husband is a laborer and he can barely afford our food. That is why I stuck the ad for selling my kidney on the wall of the dialysis ward of Golestan Hospital in Ahvaz. God willing, perhaps somebody will buy it and I can solve the problems of our life.”

In April, Ali Nobakht Haghighi, chairman of the parliament’s Committee on Health and Therapy, wrote a letter to Tehran’s Prosecutor Abbas Jafari Dowlatabadi, asking him to shut down websites that deal in body organs, including koliee.ir, which presents itself as a site for “donating” kidneys [Persian links]. He explained that he fears international gangs that smuggle body organs will extend their activities across Iran. But no action has been taken. In the meantime, a simple search on Instagram brings up dozens of pages dedicated to buying and selling body organs and babies and also for “renting” surrogate mothers to carry somebody else’s fertilized egg to term.

University student Saeed, 22, who lives in Tehran, is one of those who has posted an ad online. His father is dead and, as the oldest child, he has been trying to pay the costs of his own education and provide for his two young sisters at the same time. He says that jobs are very scarce and their rent is higher than ever. In addition, their mother suffers from severe depression and is unable to perform even the simplest tasks. Saeed’s blood type is O+ and he hopes to sell his kidney for 35 million tomans, or close to $8,4000, so he can pay rent and other expenses.

Mehrdad is a young man of 30 who lives in Tabriz. He wants to sell his kidney to bring home his wife after four years of being legally married to her. “My wife’s family is very understanding and patient but if I want to hold even the most humble ceremony and provide her with the most humble living quarters I need a lot of money.”

Mehrdad has not told his wife that he plans to sell his kidney. “I was working for a private company but they downsized and I have been unemployed for the past two years,” he says. “I have a degree in computer science from a state university but no matter where I go for a job, they offer a salary of under one million tomans [around $240]. This will not even pay for my transportation, let alone allow me to save some money or support a wife. My father is old and retired and at best he can help me with five million tomans [$1,200], whereas I need at least 50 million tomans [$12,000] to start my married life — not a life of luxury and comfort, but the most modest one renting a cheap and small studio or apartment.”

He says he will tell his wife, but only after the surgery. On the whole, compared to the woman in Karaj who sits every day at the corner of a street to save her son, Farhad is in an enviable heaven.

More on poverty in Iran:

Living on the Margins in Iran: Chabahar and the Province of Sistan and Baluchistan, September 6, 2018

Can Iran Survive the Inflation Hike?, August 29, 2018

Living on the Margins in Iran: Bandar Abbas and Hormozgan Province, August 24, 2018

Living on the Margins in Iran: East Azerbaijan, August 23, 2018

Living on the Margins in Iran: Mashhad and the Cities of Razavi Khorasan, August 17, 2018

Living on the Margins in Iran: An Introduction, July 11, 2018

The Guards’ Fight Against Poverty: Where Does the Money Come From?, June 14, 2018

Iranians Are 15% Poorer than a Decade Ago, January 9, 2018

Please Help Stop the Sale of This Baby Girl, October 5, 2017

More than 40% of Iranian Households Live Below the Poverty Line, October 2, 2017

Child Trafficking by the Truckload, July 7, 2017

Stories From Iran's "Kidney Street", February 28, 2016

Hundreds of Thousands of Tehranis Living In Poverty, June 16, 2015

Death of a Fruit-Seller: Is the Government to Blame?, April 23, 2015

Wasted Youth: The Hidden Trash Collectors of Tehran, December 2, 2014

Iran's Real Emerging Market: Kidneys, November 21, 2013

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments