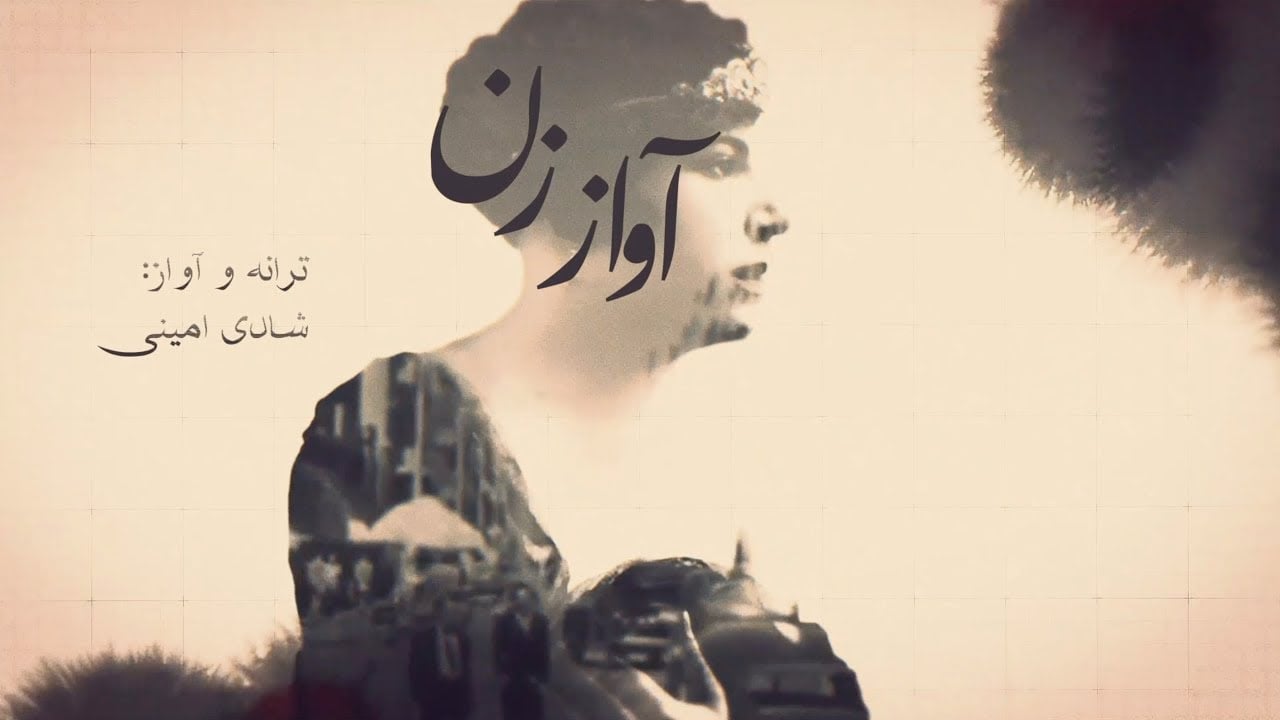

IranWire is the first to publish the music video of Woman’s Song by Shadi Amini. The video highlights and features photographs of Iranian women singers, who are banned in Iran. The video is both a lament for the ban and a tribute to women who have been steadfast in their efforts to keep their voices alive.

Shadi Amini was born in 1986 in Tehran and holds a degree in urban engineering. She left Iran when she was 24 and started her career as a professional singer in 2012 with a single entitled "Bed." She currently studies visual arts at the University of California and has released one album and several singles. She says that her performance of each song has a specific message for her audience and that she hopes to be the voice of young Iranian women singers dedicated to proving their talents as pop artists. Most of her songs focus on current social issues in Iran.

During her interview with IranWire to mark her new song’s debut, Shadi Amini dedicated the song to mothers whose “lullabies are brimming with love” and to all the women who throughout the years of the ban on women singing in Iran have sung with the love of music in their hearts — women who have been threatened or have been punished simply because they want to sing.

The interview follows:

Who is your intended audience?

I am addressing a way of thinking that confines women. No matter who, how and what power imposes this way of thinking, it forces limitations and hopelessness on half of the society to which I belong.

Does this work reflect your own experience in life?

Yes, it is work that comes from my own lived experience. Since I was a child, whenever my mother and my aunts got together they would pick up the microphone to our tape recorder and sing, together or individually, and record. They all loved singing. Singing together perhaps made them feel good and for a time, short as it was, it separated them from this patriarchal and sex-based society. Music has a tremendous effect on our spirits. For me personally, music was a way to save myself from depression after I emigrated. I believe that anything that, in any way, represses this love, this enthusiasm, must be condemned.

How do you see the ban on women singing in Iran?

I loved to sing. Since I was a child I was one of the ones who picked up the microphone. I loved to sing and dance. My laughs were famous among the family. I had a joyful and fighting spirit. I fought for things that I wanted and against things that I did not want, including what our culture forced on us.

But I had no idea how one could become a singer in Iran. My idea of women singers in Iran was limited to colorful images that I watched on TV, and did not go any further than that. So I knew that I had no chance of working as a singer in Iran. Nevertheless, I went to singing classes, had a private teacher to learn guitar and wrote songs, hoping that one day I would be able to perform them myself. But would it have been possible? Not if I remained in Iran. But I did not leave Iran because I wanted to sing. My singing and the release of my work started after I emigrated. The singing helped prop me up at a juncture that I had not expected and gave me hope that I could survive far from my home, my family and everything that I was attached to and were now far, far away.

Did you encounter constraints after you immigrated as well?

I believe that the Iranian music market [outside Iran] is a little male-centered. This strikes you if you go to music-specific websites. Compared to female singers, the number of male singers is much higher. This shows the restrictions that women have in this field and a major part of it comes from our culture.

The other reason is what people expect from a woman singer and the criteria that they set for her success, without taking into account her personal preferences. But when you choose to reflect a different kind of thinking in your music, you have to expect obstacles, whether you like it or not. We have this dominant idea — one that has been injected into our minds by the Islamic Republic — that if you are a social activist and find social problems important then you are a “political” person. I myself have been repeatedly called a “political singer” by people in the music industry who say that if my work is posted on a website, it will put others at risk because the environment becomes political.

But I am not “political.” Even at school I did not study political science. I am simply a woman who comes from a society suffering from dictatorship — a tired and distressed woman whose back is bent under so much pressure. How can I stay indifferent and blindly follow the commercial policies of the music market without thinking and by ignoring my personal preferences?

What do you believe social art’s mission should be in the face of these constraints?

I believe that art has a deep relationship to the society and they cannot be separated. They are influenced by each other and, together, they form the culture of a country. You cannot say that I am only a singer and I have nothing to do with what happens to my country and to my people.

Why do you think politicians seek out artists? They know that whatever they say is more appealing and makes a deeper impact through art. By the same measure, they are also afraid of protest art and put restrictions on the artists that enlighten people.

As I said before, I cannot be passive, close my eyes and ears and only involve myself with the emotions inside me. According to [Fereydoon] Farrokhzad [a popular variety TV show host in Iran before the Islamic Revolution] in an episode of his TV show “The Silver Carnation,” we live at a time when even our breathing is political. Then how can we remain indifferent? There are many who say they have nothing to do with politics. They close their eyes and pretend not to know what they are doing to people.

I believe that until and unless we learn to accept responsibility and demand our rights, our situation will remain as it is. Politicians come and go but we still have not learned to stand together and we still remain passive.

What do the two words “mother” and “lullaby” in your song stand for?

They stand for womanhood. We go to sleep, we wake up and we experience our world with our mothers’ humming. The way of thinking that stands against this feeling and suppresses it has to deal with an inevitable reaction. Do people who think this way find a mother’s lullaby [sexually] arousing? Do such sick minds have the right to oppress and hold back half of the people in the society? Should the rights of women in a society be decided by a bunch of fossilized and sexist individuals who see everything from the viewpoint of men’s arousal?

My mother sang all the time — in the kitchen while cooking and even when she was busy with her daily chores around the house. She was not a professional singer and never in her whole life had she had lessons in singing, but her humming and her voice was what gave our home its warmth. No law can imprison a mother’s humming in her throat.

In your song you compare your art to madness. What kind of madness are you talking about?

Every professional artist wants to present her art to other people. Music and singing are popular arts and you can develop them only if they are presented to people. You must be able to publish your work publicly. Underground and banned music brings no income to women singers so, after a while, they get discouraged, give up and let it go. What is more, it can lead to security problems for them. A number of my girlfriends who are singers in Iran are caught up in courts and legal problems. I have loved singing since I was a child. Love and madness together. I clung to it. Or maybe it was singing that clung to me and the madness that did not leave me.

Why, in your song, do you compare women’s singing to the “sound of love”?

The sound of love is the repressed voice of Iranian women, the voice of mothers who might have loved to sing but swallowed their frustration and expressed this love by singing lullabies to their children. And I believe all the efforts to repress women’s singing have failed. Right now, there are thousands upon thousands of young women across Iran who sing and post [these songs] on social media. We have repressed this frustration for years but now the repression is showing cracks and nobody can stop us.

In the song you also encourage or admonish members of your audience. Who are they?

It is quite clear. They are those who must know that, at this juncture, Iranian woman are not supposed to stay back. These days you can see a lot of videos of women’s civil resistance in the streets and in public. This government and the guardians of its power must know that Iranian women will no longer yield to this bullying and humiliations. I especially have high hopes for the new generation. A generation who, thanks to social networks and activists, is much more informed and daring than previous generations, it is ready to fight for its rights, to demand its rights and to resist bullying.

To whom this song is dedicated?

This song is dedicated to all the mothers whose lullabies are brimming with love and to all the young women who throughout these years have sung and have created works of music under the most difficult conditions — but have been treated like criminals, have been arrested, have been interrogated and have been even sentenced so as to force them to forget their dreams. But dreams never die.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments