A senior Iranian national security official has publicly announced that Iran and the Taliban have been engaged in talks for years, and that the Afghan government has been fully aware of it.

Rear Admiral Ali Shamkhani, the Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, made the comments during a visit to Kabul, where he was scheduled to meet with his Afghan counterpart Hamdullah Mohib and other senior political and security officials. Talks between Iran and the Taliban were held “to help curb the security problems in Afghanistan,” Shamkhani said.

The public revelation contradicts earlier denials and hedging from Iranian diplomats and officials. In May 2018, Mohammad Reza Bahrami, Iran’s ambassador to Afghanistan, said that Iran has had “contact” with the Taliban but that no significant “relations” had developed [Persian link]. “We did not turn these contacts into relations because we did not want to bestow legitimacy on the Taliban,” he said. Whatever he was indicating by this statement, the ambassador clearly wanted to obfuscate the issue.

But the fact is that the Islamic Republic of Iran has been in touch with the Taliban since 1995, and at high government levels. Talks between the two sides have never been completely broken off — even when Taliban forces killed Iranian diplomats in 1998 in the Afghan city of Mazar-e Sharif.

1996: Iran’s Special Envoy Meets the Taliban in Kandahar

Morteza Sarmadi, the current deputy foreign minister, is one of the highest-level Iranian diplomats to have negotiated with the Taliban in the Afghan city of Kandahar. In 1996 he visited the city as Iran’s special envoy, with the sole purpose of talking with the Taliban.

In the spring of 1995, Alaeddin Boroujerdi, who was then deputy foreign minister, had reported that contacts between the Islamic Republic and the Taliban were underway. A year before Sarmadi visited Afghanistan, Boroujerdi said that the Taliban had accepted Iran’s proposal to guarantee the safety of non-combatants in Kabul and that the two sides had negotiated about drug trafficking and other issues concerning the border between the two countries.

A month after Sarmadi’s visit to Kandahar, in September 1996, the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei called “fratricide” in Afghan “inhuman” and said that the Taliban were “strangers to Islam,” and also that the United States had established the Taliban “to fight Iran.” If the leader hd made those comments today, this could have signaled a change in the Islamic Republic’s policy of talking with the Taliban, but two decades ago the political and diplomatic climate was vastly different.

At the time, Alaeddin Boroujerdi said that, like the Supreme Leader, the foreign ministry also believed that “nobody has the right to make the beautiful face of Islam ugly.” Nevertheless, Iran-Taliban negotiations continued and in December 1996, Ali Akbar Velayati, the foreign minister at the time, reported that a Taliban delegation had arrived in Tehran.

Contact between Iran and the Taliban continued, as did meetings between Iranian officials and Taliban leaders, both in Iran and Afghanistan, until the early summer of 1998. In the meantime, the Taliban had succeeded in occupying a larger area of Afghanistan. Even though the talks went on, Iran supported the Afghan government of Burhanuddin Rabbani and Ahmad Shah Massoud, commander of the Northern Alliance, who were fighting against the Taliban.

Then, in the summer of 1998, the Taliban kidnapped 11 Iranian diplomats from Iran’s consulate and transferred them to a military base. This led to tensions between the two sides and Iran was helpless in its efforts to secure the release of its diplomats. Foreign Minister Kamal Kharrazi appealed to the UN secretary general to intervene but, as the crisis dragged on, several diplomats were dispatched to the Iranian consulate in the city of Mazar-e Sharif at the behest of Alaeddin Boroujerdi.

The Taliban Kill Iranian Diplomats

Shortly afterward, on August 8, 1998, the Taliban captured Mazar-e Sharif, attacked the Iranian consulate and, in addition to massacring their enemies, killed Iranian diplomats and a correspondent from the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA).

With the killing of the Iranian diplomats, relations between Iran and the Taliban entered a new phase the Islamic Republic had probably not expected. Iranian armed forces mobilized to strike at the Taliban’s positions on Afghanistan’s border with the Iranian province of Khorasan. In Early September 1988, US spy satellites spotted 70,000 Iranian troops and 150 tanks on the Afghanistan border. But Ayatollah Khamenei, who is also the commander-in-chief of Iran's armed forces, declared that he would issue his orders when the time was right. In other words, he held off attacking Afghanistan and the Iranian military were pulled back.

At the same time, the Mojahedin of the Islamic Revolution of Iran Organization (MIRI) suggested that, to secure the release of Iranian diplomats who had been taken prisoner and to retrieve the bodies of those who were killed at the Mazar-e Sharif consulate, Iran must enter into negotiations with the Taliban.

It did not take long for Ayatollah Khamenei’s inner circle to attack this proposal, saying it showed a willingness “to compromise with the enemy.” The Iranian foreign ministry then announced: “The decisive policies of the Islamic Republic have been responsible for the Taliban accepting many Iranian demands, including the return of the bodies of those killed at the consulate and the release of captured diplomats.”

After this episode, Iran consistently referred to the Taliban as a “Sunni extremist paramilitary” group whose religious views had nothing to do with Islam. In early 1999 the Iranian government announced that it would never recognize the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan.

After the massacre of Iranian diplomats at Mazar-e Sharif, relations between the two sides were never the same, but even so, talks between Iran and the Taliban continued.

Talking with the Taliban While Helping the US to Fight Them

While events were unfolding, the UN Security Council “strongly” condemned the murder of the Iranian diplomats and passed a resolution imposing an arms embargo on the Taliban. Russia and Iran agreed to enforce the embargo.

Ahmad Salek, Khamenei’s representative to the expeditionary Quds Force, said that the Taliban rejected all manifestations of technology and that they had been put in power to distort Ayatollah Khomeini’s theory of Islamic government. And Hassan Rouhani — at the time Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council — called the Taliban “an extremist group,” a “danger” to Afghanistan’s security and an obstacle to the country’s progress.

The Islamic Republic no longer trusted the Taliban but, contrary to what is generally believed, talks between the two sides still continued. In early 2001, the Iranian foreign ministry confirmed that “certain contacts and unofficial talks” with the Taliban had taken place and reported that the “private sector” in Khorasan, the province bordering Afghanistan, had sold fuel to Taliban representatives.

Meetings between Iranian officials and the Taliban were not conducted in secrecy. Even Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef, Taliban’s ambassador to Pakistan at the time, gave interviews to IRNA and talked about the Taliban’s interest in negotiating with Iran. After the Iranian consulate in the province of Herat was attacked in the spring of 2001, the Taliban assured IRNA that the perpetrators would be found and would be punished according to Islamic sharia laws.

At the same time, Tehran newspaper Ettela’at reported that UN observers were going to be stationed in Iran, Pakistan and Tajikistan to prevent the Taliban from receiving arms and ammunition from outside.

This was the situation when, on September 11, 2001, members of Al-Qaeda hijacked planes and flew them into the Twin Towers in New York and the Pentagon, killing thousands. Osama bin Laden, Al-Qaeda’s leader and a guest of the Taliban in Afghanistan, took responsibility for the biggest attack on the American mainland in modern times.

The 9/11 attacks were followed by the US declaration of “war on terror” and the invasion of Afghanistan to bring down the Taliban and to destroy Al-Qaeda. After the invasion started, Iranian officials repeatedly announced that the Iranian military, including the Quds Force with its good knowledge of the terrain in Afghanistan, had provided vital support for US forces and their allies, expediting their victory over the Taliban and Al-Qaeda.

In spite of this unprecedented cooperation, shortly after the invasion, President George W. Bush, in his State of the Union address to the US Congress on January 29, 2002, accused the Islamic Republic of aiding the Taliban and Al-Qaeda and accused Iran of being part of what he called the “Axis of Evil” alongside Iraq and North Korea.

The presence of Al-Qaeda and Taliban agents in Iran was an open secret. One of them was Osama bin Laden’s son, who lived at the Saudi embassy in Tehran and who later accompanied his mother to Syria. It was not quite clear whether Iran was supporting the fight against the Taliban or was supporting the Taliban with arms and money. This policy continued into the 2010s.

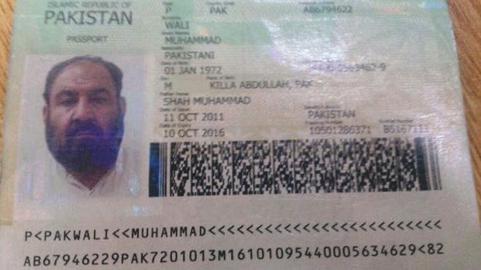

This perplexing policy was highlighted when American drones killed Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, the leader of the Taliban, on May 21, 2016 in the Pakistani province of Baluchistan. His passport, found by the Pakistanis at the scene of the attack, included a valid Iranian visa and it was even speculated that he had visited Iran before his death.

Why is Iran’s Policy Toward the Taliban so Puzzling?

When the Taliban controlled a large part of Afghanistan, the group and Al-Qaeda carried out bombings in various countries, including the bombings of American embassies in Nairobi, Kenya and Dar-e-Salaam, Tanzania, in 1998, which led President Bill Clinton to retaliate by ordering cruise missile strikes on Afghanistan. But Al-Qaeda did not carry out large terrorist attacks in Iran despite fundamental ideological differences with the Shia government of the Islamic Republic.

After the invasion of Afghanistan, Iran was under intense pressure by the administration of President George W. Bush to extradite members of Al-Qaeda and the Taliban to the United States, but the Islamic Republic refused to do so. Perhaps if Iran had gone along with this demand, relations between the Islamic Republic and the West, especially the US, would have improved. But it appears that Tehran decided not to openly ally itself with the United States so as not to give the Taliban and Al-Qaeda a reason to carry out terrorist attacks against Iran. The same reasoning can be applied to Iran’s continued negotiations with the Taliban.

Now, years after the 9/11 attacks and so much else that has happened since then, it is the United States that is publicly negotiating with the Taliban.

In recent months US and Afghan officials have accused Iran of arming the Taliban. In late October 2018 the US Department of Treasury announced new sanctions against the Taliban and “their Iranian sponsors.” Among the name on the new sanctions list are two Iranians: Mohammad Ebrahim Owhadi and Esma’il Razavi. According to the Treasury’s news release, the two were sanctioned for acting for or on behalf of the Revolutionary Guards’ Qods Force and “for assisting in, sponsoring, or providing financial, material, or technological support for, or financial or other services to or in support of, the Taliban.”

According to Afghani officials and leaders of the Taliban, Iran and the Taliban are secretly cooperating to check the power of the Islamic State, commonly known as ISIS, in Afghanistan.

So, if in the 2000s Iran talked to the Taliban in order to prevent Al-Qaeda from targeting Iran, the excuse now is to prevent ISIS from infiltrating into the eastern borders of Iran. No matter what, the fact is that talks between Iran and the Taliban are nothing new. This behavior has been going on continuously for a quarter of a century.

The difference is that in the 2000s Iran kept its contact with the Taliban and Al-Qaeda a secret because, perhaps, it was fearful of increased pressure from the US. But now that the Americans themselves are talking with the Taliban and Iranian officials believe its missile force puts it in a stronger position, it sees no reason to continue with the secrecy.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments