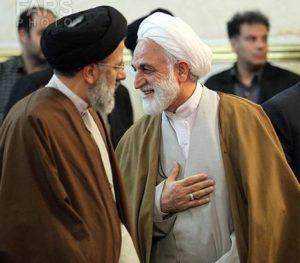

Ebrahim Raeesi, a long-serving judicial official who sat on Ayatollah Khomeini’s “death panel” in the 1980s and was a front-runner candidate against President Rouhani in 2017, has been appointed as the new head of Iran’s judiciary.

The spokesman for the judiciary Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei confirmed the appointment in his weekly press conference on Sunday, March 3.

The news of Raeesi’s ascent to the top of the judiciary first broke on February 16, announced by Hasan Nowroozi, the spokesman for the parliament’s Judiciary Committee. According to Yahya Kamalipour, a member of the committee’s board of directors, Raeesi is to succeed Sadegh Larijani as the Chief Justice of Iran on March 8.

Under Ebrahim Raeesi’s leadership, the judiciary is expected to become even more political than it already is.

Although Raeesi has held a number of prominent and high-ranking jobs in the judiciary, including as the powerful prosecutor of Tehran, he is known by many in the country for his role in the 1988 mass execution of political prisoners, which was carried out on orders of Ayatollah Khomeini. Six months before the 2017 presidential election got underway, Raeesi’s involvement in the massacre was backed up by the release of an audio file that implicated him.

So his appointment will come as a huge blow to campaigners for justice — though it may not come as a surprise. At a time when the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei is faced with seemingly endless rounds of protest, from teachers and female football fans to fishermen and steelworkers, the Leader is taking steps to ensure his authoritarianism can be firmly backed up in the courts.

A Long Career in the Judiciary

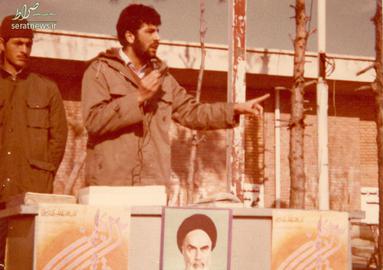

Ebrahim Raeesi, 59, was born in the holy city of Mashhad and is the son-in-law of Ahmad Elmolhoda, Mashhad’s controversial and hardliner Friday Imam. In 1980, at the age of just 20, he started work as the assistant prosecutor of Karaj county near Tehran, and was promoted to prosecutor a short while later. In 1982, he was also appointed as prosecutor of Hamadan, and worked as prosecutor in both jurisdictions. In 1984 he was appointed as acting prosecutor for Tehran; four years later was promoted to prosecutor. He served as the Chairman of the judiciary’s General Inspection Office for 10 years, from 1994 to 2004. Then he worked for another 10 years as First Deputy Chief Justice of Iran, from 2004 to 2012. From 2014 to 2016 Raeesi was the Attorney General of Iran, and in 2012 Ayatollah Khamenei appointed him as the prosecutor for the Clergy Special Court.

In 2016, Khamenei appointed Raeesi as guardian of Astan Quds Razavi (AQR), the richest religious endowment in Iran, following the death of the previous guardian, Ayatollah Abbas Vaez-Tabasi.

He has sat on the Assembly of Experts since 1997, representing the province of South Khorasan. The assembly has the power to designate and, theoretically at least, to dismiss the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic.

Ebrahim Raeesi will be the country’s sixth Chief Justice since the founding of the Islamic Republic 40 years ago. The first was Seyyed Mohammad Hosseini Beheshti, who was appointed to his post on February 23, 1980 and remained and the job until June 28, 1981, when he and 72 other leading officials of the Islamic Republic were killed in the bombing of the headquarters of the Iran Islamic Republic Party. He was succeeded by Abdul-Karim Mousavi Ardebili (1981-1989), Mohammad Yazdi (1989-1999), and Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi (1999-2009). The outgoing Chief Justice, Sadegh Larijani, was appointed in June 2009, the same month that Iran held the widely-contested election that ushered Mahmoud Ahmadinejad into a second term and was marked by huge street protests and thousands of arrests and prosecutions.

The Failed Promises of Sadegh Larijani

Sadegh Larijani started in the job by announcing that he intended to reform the judiciary — and he did present a reformist and law-abiding figure of himself when he put a stop to the highly-criticized televised trials of protesters.

But this even-handedness did not last. His unprecedented unanimity with Ayatollah Khamenei in politics and in the guiding policies of the judiciary, combined with his granting of an iron-clad immunity to security forces affiliated with the Revolutionary Guards, led to many deaths in detention centers as a result of mistreatment and torture. Sattar Beheshti, Mohsen Rouholamini, Mohammad Kamrani, Amir Javadifar and Ramin Ghahremani are some of the best-known detainees who lost their lives to torture, though there were many others.

Sattar Beheshti, a laborer and a blogger born in 1976, died after being tortured on November 3, 2012, only a few days after the Cyber Police took him into custody. Eventually the judiciary sentenced Akbar Taghizadeh, a Cyber Police agent and Beheshti’s interrogator, to three years in prison, two years in exile and 74 lashes on the charge of manslaughter. Before the sentence was passed, the family of Sattar Beheshti refused to attend the trial in protest against the illegal and unjust process applied to the case.

Mohsen Rouholamini, Mohammad Kamrani and Amir Javadifar died under torture in the infamous Kahrizak Detention Center. After his release from Kahrizak, Ramin Ghahremani suffered from a seizure and died on the way to the hospital.

The treatment of prisoners during Larijani’s first term in office repeatedly led to outcries, including the famous case of the journalist Hoda Saber, who died in prison 2011 due to medical neglect after a 10-day hunger strike that led to a heart attack. Under Larijani’s watch, lawyers, journalists and bloggers were arrested, critics of the regime were punished without any trial, leaders of the Green Movement were put under house arrest with any legal ruling, and the 2009 protesters received heavy sentences. In 2012, the European Union sanctioned Larijani for “gross violations of human rights.”

An Even Worse Second Term

But Larijani’s second term as Chief Justice was even worse. The number of death penalties rose and the mistreatment of detainees continued. The death of the environmentalist Kavous Seyed-Emami and a number of detainees during the nationwide protests in December 2017 and January 2018 are just two examples of this trend. The arrest of lawyers, journalists and political and civil activists continued but then environmental activists were also added to the list of “undesirable elements.”

International human rights organizations and Iranian activists have generally assessed Larijani’s 10-year tenure as Chief Justice as a firm contribution to the suppression of the press, violations of the right to free speech, violations of international conventions to which Iran had signed up to, a willingness to execute child offenders, oppression of religious minorities including the Baha’is and the Sufis, the ever-increasing interference of security agencies in the process of law, the prevention of due and unbiased process of law in security and political cases and many other instances of human rights violations.

Unlike Sadegh Larijani, who had no experience in the Iranian judiciary, his successor Ebrahim Raeesi has a long history in this arena, suggesting Iran’s human rights community will continue to face further attacks and injustices.

Raeesi: A Very Dark Past

In the years that Raeesi was First Deputy Chief Justice of Iran, many considered him to be the real power in the judiciary, but he rarely appeared in public. Although he held some of the top positions in the judiciary for almost 30 years, and despite his role in the atrocities of the 1980s, Ebrahim Raeesi has not necessarily been a prominent public figure in Iran — that is until he stood as the conservative principlist candidate in the 2017 presidential election against Hassan Rouhani.

He was regarded as Rouhani’s main rival, but Raeesi lost the election to the incumbent president by a wide margin. His opponents believed that his long record in the judiciary was his weakest point, especially after Ahmad Montazeri, the son of the late Ayatollah Montazeri, released the incriminating audio file of Raeesi’s links to the mass execution of political prisoners in 1988. Ahmad Montazeri called Raeesi’s candidacy an insult to Iranians because of his direct and undeniable role in the 1988 massacre, and Ali Motahari, parliament’s Deputy Speaker, asked Raeesi to explain his involvement.

After the audio file was published in 2016, survivors of the massacre testified that Raeesi was a member of the “death panel” ordering the executions. During the campaign for the presidency, Raeesi denied having played any part in the executions and in late 2018 he repeated this denial. Eyewitnesses confirm that he was involved in the execution of over 5,000 political prisoners. During the presidential campaign of 2017, Ayatollah Khamenei referred to the 1988 execution of political prisoners as an event of which the regime was “proud." He did not mention Raeesi by name. And now he has appointed him to be the Chief Justice of Iran.

The appointment comes at a time when that Ayatollah Khameini is trying to set the political landscape for the era that will follow his Leadership. This project has led to widespread anxiety among sections of the public and those who keep a close eye on Iran. Raeesi’s cozy relations with the Revolutionary Guards’ security establishment will make the judiciary even more threatening and disturbing than it already is. His role in the 1988 mass executions is a very stark reminder of Iran’s continued violations of the rule of law and the rights of the people — nothing could better illustrate this than the continued disregard for a crime against humanity. So the appointment of Ebrahim Raeesi as the Chief Justice of Iran will be seen as a sign that the judiciary will continue to damage the prestige of the regime more and more, and an acknowledgment that the judiciary will continue to enshrine the pattern of abuse, corruption and injustice.

Related Coverage:

Iran’s Blood-Soaked Secrets, December 4, 2018

1988: The Crime that Won't Go Away, August 3, 2017

Ebrahim Raeesi, the Unelected Leader of Iran's Shadow Government, May 25, 2017

Who is Ebrahim Raeesi, the Man who Wants to Take Down Rouhani?, May 18, 2017

"A Raeesi Presidency Would Mean a Military Government", May 16, 2017

Ebrahim Raeesi: Political Novice with no Flair for Public Speaking, April 28, 2017

Ebrahim Raeesi, A Candidate with a (Very) Dark Past, April 7, 2017

My Father, the 1988 Massacre and the Need for Truth, April 5, 2017

Iran Still Haunted by its “Biggest Crime”: the 1988 Prison Massacre, September, 2016

Montazeri and the 1988 Massacre of Prisoners, August 12, 2016

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments