In the second of a two-part series, a citizen journalist using the pseudonym Mohammad Sharifi Moghadam reports from Fashafuyeh Prison, also known as the Greater Tehran Penitentiary.

In March 2018, during one of my interrogations, I spent four days at Division 1, Ward 11 — the same ward where Alireza Shir Mohammad Ali was murdered. The ward has nine small cells and a three-meter-wide corridor that leads to three service rooms on the right side and three bathrooms on the left. After the stories I have heard from some inmates and guards, for days now I have had this image in my head of the dagger that stabbed the neck of this political prisonerm whose courage and will could only be stopped by cutting the veins in his neck.

The saddest of all, however, was his hunger strike only a few months before this tragedy. He went on hunger strike to protest against the violation of the law [that orders the] separation of prisoners of conscious from dangerous criminals, [set out] by the Prisons Organization and the judiciary. Here I want to touch on certain aspects of this issue. The stories I quote are from my student and dervish friends in Fashafuyeh and Gharchak prisons.

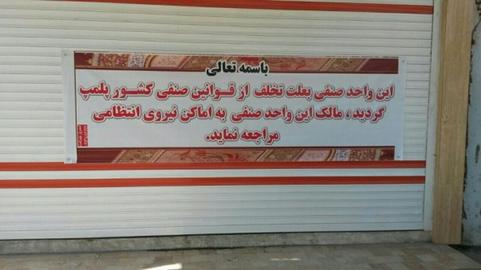

What happened is this: especially over the last two years, they have sent many prisoners of conscience and political prisoners to to serve their sentences at prisons and wards [allocated for people serving time] for crimes such as murder, theft, violent fights, etc. This is against the laws and the bylaws of the Prisons Organization. The first question that comes to mind is: Why do the judiciary and the Prisons Organization insist so blatantly on violating this law — something that in the last six months has cost the lives of at least two political prisoners in Fashafuyeh and Gharchak?

The main reason behind such actions is to pressure the prisoner. If the prisoner “breaks” and repents, then security forces declare victory and, in their view, the case is closed. One action [they take] is transferring the prisoner to an unsafe ward where his life will be in danger — wards where other prisoners can be enticed to pose every kind of threat to the political prisoner.

A political prisoner at Ward 5 of Division 1 of Fashafuyeh Prison describes this unsafe ward as follows: “Our ward has 500 prisoners and 16 rooms. Each room has five triple bunkbeds, meaning that around 200 must sleep on the floor. Until a month ago, I myself slept in the corridor. Every morning one person from each room has the task of making a sharp instrument when he goes to the yard to get air. He takes parts of railings, ceiling supports or the sides of gutters and sands them down to make sharp instruments such as daggers. Besides small quarrels, every week we have a serious fight that lasts an hour or two. In these situations, if I am lucky, I hide in a latrine. The prison doesn’t care if people are killed or injured. Such fights are inevitable when a person does not have even one meter of space to himself.”

From Margins to Wilderness

A large number of these prisoners are people who have ended up in prison because they come from the margins of society. And prison does not make their situation any better. Without a doubt, it widens the divide between these people and the society outside the prison. Many political prisoners have recently gathered a vast amount of information about the unfavorable conditions of prisoners and prisons across the country, but these details are beyond the scope of this article.

Apart from the [poor] general conditions in Iranian prisons, political prisoners have been repeatedly beaten by other prisoners who have been enticed and ordered to do so [by prison staff].

Violating the law that says prisoners should be separated by the type of crime they have committed has other advantages for the judiciary as well. The political prisoner is isolated and is denied any chance for meaningful conversation, exchange of ideas and other social interactions. Getting exact statistics about the number of political prisoners has become impossible and the political prisoner cannot easily communicate with the outside world to inform it of his exact situation. In fact, we do not know how many students, workers, protesters and online activists are currently in prison in Iran. We only learned about that political prisoner’s hunger strike in Qom after he was killed.

The Weakening Power of Deterrence

But in addition to what happens to political prisoners inside such prisons, the other important answer to the question why [authorities] violate the law of prisoner separation must be sought outside the prison walls. Apart from removing the political convict from society, prison has another function as well: deterrence. Incarcerating criminals helps to deter potential criminals from committing crimes. Deterrence is the reason the judiciary has been making life more and more difficult for political prisoners.

In recent times, economic and political pressures led to a vast outbreak of discontent among all segments of the society. Look at student rallies in universities, labor protests and strikes, rallies and protests by teachers, protests against mandatory hijab and last year’s street protests, all of which were met with repression and arrests. But the social and economic crisis in Iran has reached a level that has weakened the power of deterrence and the threat of incarceration.

The student who has been silenced by force will continue his activities even though he knows full well that he might get arrested. The worker or teacher who cannot make ends meet will not stop shouting for his rights. And this is true of other activists as well. This is what has made the regime add “the threat of death” to prison sentences for political prisoners. The message of deterrence sent to the people and political activists is this: whoever protests or dares to dissent will be sentenced not to prison but to “prison with a chance of death.”

But let me return to Ward 11, where Alireza Shir Mohammad Ali was murdered, and to what other inmates have told me.

When I asked an inmate held at the same division [as Shir Mohammad Ali] about the murderers, this is what he told me: “A few months ago Tehran’s assistant prosecutor visited the prison and met some of [the political prisoners who have been dispersed among common criminals]. He told them that he had reported the situation to the attorney general and the deputy chief of the judiciary. Two weeks before Alireza was murdered, families of political prisoners wrote a letter to Asghar Jahangir, head of the Prisons Organization, and told him about the dangerous situation for their children. The letter was written at the suggestion of Gholamreza Moghtadai, Inspector General of the Prisons Organization. During the previous six months Moghtadai had visited the prison at least twice, had talked to some of the prisoners and knew well how dangerous their situation was. Mostafa Mohebi, Director General of Tehran Prisons Organization, was the one who, on August 29, 2018, personally ordered the transfer of 50 prisoners of conscience and political prisoners to various wards of Fashafuyeh — two per each ward. Prisoners and families had told Farzadi, chief warden of the prison, more than a hundred times about the violation of the law [to separate prisoners] and each time he had answered: ‘I do this on direct, written orders from the judiciary. I am only carrying out the judiciary’s orders.’ Every time that I myself met Azimi, the prison’s deputy warden for health, I told him that he was responsible for the lives of our fellow inmates, and each time he just laughed.

“Yes, I saw the faces of the murderers but they were not behind bars. They were in front of the bars.”

That is all.

Related Coverage:

A Prisoner’s Tales of Drugs and Prostitution Inside an Iranian Jail, June 25, 2019

IranWire Exclusive: Interview with Cellmate of Slain Political Prisoner, June 24, 2019

Political Prisoners Demand Justice for Murder of Fellow Inmate, June 20, 2019

More Violence in Tehran Prison as Judge Accuses Dervishes of Being “Rioters”, June 20, 2019

"My Son Was My Reason to Live. They Took Him Away from Me”, June 15, 2019

Political Prisoner Murdered While Awaiting Appeal, June 12, 2019

Riots Endanger Lives of Political Prisoners, May 10, 2019

200 Dervishes Remain in Prison, February 14, 2019

A Young Iranian’s Memory of Torture, Humiliation and Urine, January 29, 2019

Prison Life and the Big Business of Smuggled Knives, December 14, 2018

Expired and Counterfeit Medicine for Prisoners, November 23, 2018

Gonabadi Sufi Dies in Prison, March 5, 2018

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments