The appellate Revolutionary Court in the province of Yazd has placed severe restrictions on the movements of a Baha’i man as punishment for proselytizing and “propaganda against the regime.”

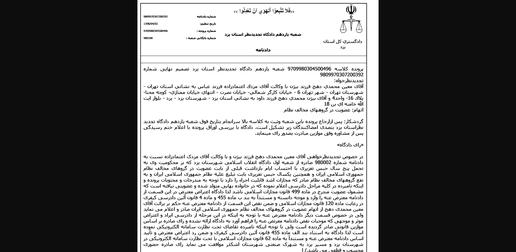

The one-year “electronic” sentence was handed down to Moein Mohammadi Dehaj. The official charge against him is “propaganda against the regime under the cover of proselytizing for the Baha’i faith in cyberspace.” Mohammadi is only allowed to move within Yazd city limits or between the city and his workplace at the industrial park at Ashkezar, and must wear "digital shackles” — an electronic ankle or wrist bracelet tracking device.

Since 2014, Iran’s Islamic Penal Code has allowed for electronic monitoring and courts can offer it to defendants who have been sentenced to a maximum of five years in prison.

“We asked the appeals court judge for an electronic ankle bracelet,” Moein Mohammadi said. “The limitations on my movements were also set to include my workplace at Ashkezar. Until the verdict is carried out it is not clear whether I will have to wear an electronic ankle bracelet or a wrist bracelet. In any case, they are designed to send an alert to [the authorities] if they are not on my body. It would appear that I also have to post a deposit for the bracelet in case the tracking device is damaged.” He also said he has to pay a “monthly rent” for the device.

Mohammadi says he has committed no crime and that he will only be happy once he is exonerated and his reputation is restored. He also says the surveillance device is likely violating his right to privacy.

The Criminal Hashtag

The preliminary court verdict stated that Mohammadi’s tweets and his creation and use of the hashtag “#Life_with_Discrimination” (#زندگی_در_تبعیض) was proof that he was guilty of propaganda activities.

Plainclothes officers arrested Moein Mohammadi on the street on January 9, 2019. He was released on bail on April 10 after three months in detention, pending the court’s verdict.

Mohammadi denies that he created the hashtag “#Life_with_Discrimination” and says he has only been found guilty because he is a Baha’i. He says the hashtag was created on October 9, 2018, by Shahrvand-Yar (“Citizen’s Friend”), an NGO that defines its mission as paving “the way to achieve a stable democracy in Iran” via organizing workshops that “raise awareness through modern methods, and create simplified, brief, and interesting content in the fields of civil society, democracy, and human rights.”

Moein Mohammadi told IranWire that he had written on the NGO’s site about the discrimination he and his family had faced, accompanied with the offending hashtag. He has taken university entrance exams three times — and three times he has been rejected on grounds of having an “incomplete dossier,” a term used in recent years to prevent Iranian Baha’is from pursuing higher education.

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, numerous Baha’is have been denied higher education despite having passed nationwide entrance exams. A few were accepted into universities, but when it was discovered they were Baha’is, the university security offices gave them two choices: Renounce the Baha’i faith and continue their education or face expulsion.

Mohammadi wrote about the university on his #Life_with_Discrimination post, but also about his family’s painful memories of discrimination — from his elderly grandfather whose retirement pension was cut off because he was a Baha’i to his mother, who was expelled from her job for the same reason. He wrote about his mother’s grandfather, who had died before the Islamic Revolution, but saw all his assets confiscated after the revolution as punishment for “membership to the formal Baha’i organization,” and because of his relationships with seven Baha’is who the Islamic Republic executed in 1980.

Baha'is have also been denied the right to freely choose their occupation since the 1979 revolution. Authorities give various excuses for shutting down Baha’i-owned businesses, and they often confiscate their properties.

“Certain Clarifications”

“The first time I was targeted was in September 2018, when somebody called my mobile phone and summoned me to Yazd’s security police for ‘certain clarifications,’” Mohammadi said. “I did not go because I had not received an official summons. On October 7, the agents came to our residence with a search warrant on the charge of ‘disturbing public order’ and confiscated books, personal effects, photographs and whatever had anything to do with the Baha’i religion. The search took place when I was not home. All security action against me took place before the hashtag #Life_with_Discrimination began. This shows that my arrest and the charge of setting up this hashtag was without any merit and it was only a cover to hide [the real reason] — i.e. being a Baha’i.”

“At around 7am on the morning of Wednesday, January 9, as I was driving out of the alley into the street to go to my workplace, a [Citroën] Xantia car blocked my way,” Mohammadi said about his arrest. “The passengers of the car got out, showed me a warrant, arrested me and took all my identification documents. I was just 50 meters away from my home so I asked them to allow me to tell my family but they didn’t. They handcuffed and blindfolded me and took me to Yazd’s Revolutionary Court. At Branch 6, Vahid Parhizgar, the examining magistrate, read me my charges.”

He was first charged with “actions against national security,” “propaganda against the regime” and “membership to an anti-regime group,” but the charge of acting against national security was dropped during the interrogations.

The Spelling Crime

Moein Mohammadi remembers the first interrogation session well.“The examining magistrate pointed to the hostility my tweets hinted at, and that of others using the same hashtag. He also said that my use of an older spelling for ‘Tehran’ showed hatred. I reminded him of statements made by Mr. Mohammad Javad Zarif at international forums, when he said that the belief in the Baha’i religion is not a crime. The magistrate replied that Zarif is a politician and is ignorant of Iranian laws. ‘The law does not specifically mention Baha’ism as a crime, which would give law enforcement room to show benevolence when dealing with it, but this does not mean that Baha’is are not criminals,’ he added.”

After questioning, the agents handcuffed Mohammadi and took him to his father’s workplace at Ashkezar industrial park. They entered the premises without announcing themselves. After carrying out a search and confiscating attendance records, invoices, computer hard drives and DVDs linked to the CCTV system, they left and handed Mohammadi over to the Intelligence Bureau.

The moment he entered the detention center of the Intelligence Bureau, the interrogations started. During the first sessions of interrogations, he told them he refused to answer their questions while he remained blindfolded and facing the wall. Afterward, Mohammadi was allowed to call his family for the first time after his arrest.

According to Mohammadi, the interrogators questioned him about his tweets with the discrimination hashtag and about specific texts he had sent to his friends on Telegram and WhatsApp Messenger.

After a week, Moein Mohammadi was transferred from the Intelligence Bureau’s detention center to Ward 10 of Yazd’s central prison. The ward is designated for prisoners still under investigation and who are not allowed any contact with the outside world as a punishment for their refusal to cooperate. After a few days, with the consent of the examining magistrate, he was transferred to Ward 9, where prisoners of conscience and political prisoners are held. The ward is not signposted, and most inmates held there have no idea that it even exists.

Compared to other wards, Ward 9 is clean and orderly. It is scrubbed every day and the inmates have their own yard for taking in fresh air. When Mohammadi was there, there were only 18 other inmates on this ward, and he said prison officials treated them inmates with respect. The prisoners are not allowed to leave their ward and mix with other prisoners but the officials often allow them to leave their cells.

In mid-March, Mohammadi was taken from the prison to Branch 1 of Yazd’s Revolutionary Court for his trial. Judge Mohammad Reza Dashtipour listened to the charges against him, “membership to groups opposed to the Islamic Republic” and “propaganda against the regime for the benefit of opposition groups.” During the trial, Mohammadi was not asked any questions and his defense was submitted to the court by his lawyer in writing. After 20 minutes, the judge declared that the trial was over and he was returned to the prison.

On March 25, his lawyer was informed of the verdict. Regarding the charge of membership to anti-regime groups — meaning the Baha’i community — he was given the maximum sentence of five years in prison. He received an additional one-year sentence for propaganda against the regime by proselytizing for the Baha’i faith.

“I was released on bail after three months,” Moein Mohammadi said. “My detention was prolonged illegally. My lawyer could not find any document or letter in my file that should extend my detention after the first month. And, according to the law, an accused person cannot be detained longer than the minimum prison sentence for the charge against him. The minimum sentence for propaganda against the regime is three months in prison so, legally, they were not permitted to keep me in detention longer than three months.

“All Baha’is are Spies”

On June 18, Mohammadi’s case was tried at Branch 11 of Yazd’s Revolutionary Court of Appeals, presided over by Judge Mahmoud Eslami. At the trial, the judge explicitly told him that Baha’is have no rights in Iran. “In our view, Baha’ism is not a faith or a religion,” said the judge. “It is only an espionage network and all Baha’is are spies.”

About 20 days later, the appeals court issued its verdict. Since, according to the indictment, Moein Mohammadi was only born to a Baha’i family but was not an official “member” of the Baha’i community, he was cleared of the charge of membership to anti-regime groups, but his one-year prison sentence for propaganda against the regime was upheld. The verdict allowed him to serve his sentence through being monitored by electronic tracking.

Moein Mohammadi was targeted because of his faith, but he is also an environmental activist. “My arrest and sentencing were only because I was a Baha’i and the verdict said nothing about this subject,” he said. “Even during the first session the examining magistrate told me: ‘you are a fan of nature and mountains and caves. Follow your cave explorations. What do you want to do with propaganda?’ I am an environmental activist and work for the health of the environment around me. Even when I was at the detention center of the Intelligence Bureau, I talked to the interrogator about rumors of a treasure hunt in a cave near Yazd. I am trying to prevent its destruction because this cave is part of our national heritage and it belongs to all Iranians.”

Related Coverage:

Baha'i Man Missing for Six Months, July 22, 2019

Baha’is Denied Family Contact as they Mark Two Months in Jail, June 28, 2019

Raids on Baha’i Businesses and Homes in Shahin Shahr, June 27, 2019

36 Years On: The Baha'i Teenager Executed for Educating, June 18, 2019

Official Jailed for Defending Baha'is, June 4, 2019

A Month After Their Arrest, No News of Three Baha'is in Semnan, June 2, 2019

Baha'is in Small Towns Also Face Persecution — It's Not Just About Tehran, March 19, 2019

Iranian Court Rules that Being a Baha’i is Not a Crime, January 14, 2019

Persecution of Baha'is Continues With 60 Arrests and Interrogations, January 8, 2019

Baha’is Go to Prison for Praying, November 16, 2018

Six Baha’i Environmentalists Arrested, September 25, 2018

Mass Arrests of Baha’is in Shiraz, August 28, 2018

40 Years of Discrimination Against Baha’is and Sunnis, August 13, 2018

Foreign Minister Zarif: What Baha’i Prisoners?, April 27, 2018

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments