“I only confessed so they would stop hitting me with a cable and torturing me. They would stretch me on a bed and would hit me with a cable as much as they could. They laughed and told me that my feet were as big as my head. The day of my TV confession I could not walk. Two of them carried me by holding me up by my armpits and sat me down on a chair in front of the camera. I had to repeat whatever they told me. They had warned me that if did not repeat exactly what they said they would beat me so much that no flesh would remain on my bones. My mother had a heart attack when she saw my confessions on TV and she has yet to recover. For 16 months my family did not know where I was. Then a go-between told them that if they gave him $50,000 he would tell them where their son was. So they sold my car and gave him the money merely to learn where I was. Then they told my family that if they gave them a billion tomans [$85,000] they would reduce the death penalty to life in prison.”

The transcript above is from IranWire’s exclusive interview with Mazyar Ebrahimi, was one of the people accused of assassinating four Iranian nuclear scientists. He is currently in Europe, hoping to be granted asylum. Read parts one and two of the interview.

The story of Ebrahimi’s arrest, torture and TV confession paints a lucid picture of the depth of violence, injustice and corruption within the Islamic Republic.

Ebrahimi was a representative for European and US manufacturers of sound and video equipment, and the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) was one of his clients. Ebrahimi says that it was the corruption at IRIB and the competition from another IRIB contractor that led to his arrest, and to his 26 months of his captivity in one of most complicated national security cases in Iran over the last 40 years.

“I have filed complaints against the intelligence ministry for its brutal torture and against IRIB for broadcasting my confessions under torture and for disgracing me,” he told IranWire. “Also, I want to ask all foreign vendors of sound and video equipment to boycott IRIB because, in fact, they will be selling instruments of torture to this organization.”

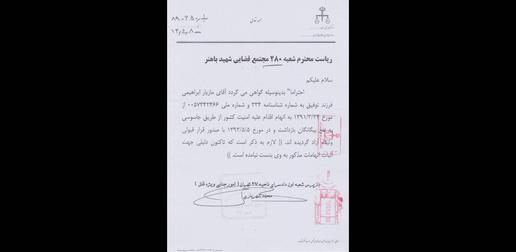

Ebrahimi said that, after enduring solitary confinement and torture at Evin Prison, he was transferred to Detention Center 300, located somewhere outside that prison. “We were blindfolded but it seemed that it was a military garrison because once in a while we heard voices [involved in] military training,” he says. “We were being tortured relentlessly. Then a man that I did not recognize came for an inspection, accompanied with a few people in suits. His left hand was cut off from the wrist and after I was released I learned that he was [Abbas Jafari] Dowlatabadi, the prosecutor. He looked into the cells and I pleaded with him to help me. He told me: ‘write down everything so that tomorrow the judge would issue his verdict and you will get out of this situation.’ He ordered them to bring me a pen, a pencil, a chair and a desk. I sat and wrote down that I am innocent. He was offended and left. I was left by myself, and the torture got worse.”

The Trial that Never Happened

On March 17, 2013, less than seven months after this visit, the prosecutor was so confident about Ebrahimi’s case that during his weekly press conference he announced that an indictment had been issued against 18 defendants arrested on charges of working with Israeli and American intelligence services and the assassination of Iranian nuclear scientists [Persian link]. He said that the defendants would be put on trial in the coming year. The trial, however, never happened.

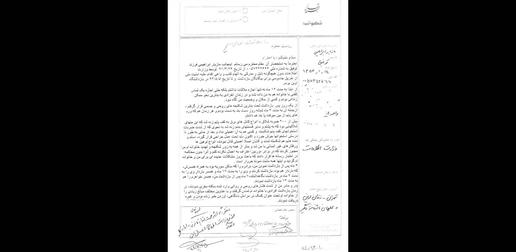

Aside from the written confessions of defendants on file, Dowlatabadi’s confidence was also boosted by a so-called “documentary” coproduced by the Intelligence Ministry and IRIB that was broadcast on August 6, 2013 (Persian video). It was supposed to document the involvement of 18 people in the assassination of Iranian nuclear scientists. Instead, the video was a mixture of supposedly reconstructed scenes, TV confessions by 14 of the accused, interviews with a few families of the assassinated scientists and footage of the intelligence minister praising his own ministry for this great success.

But this success was short-lived. By August 6, 2014, all the accused in the case were quietly released and the alleged success turned into a one of the Islamic Republic’s intelligence and law enforcement agencies’ biggest fiascos.

Mazyar Ebrahimi, the main defendant in the case, left Iran some time ago. An investigative report about him by the BBC reporter Jiyar Gol (in Persian), published on August 3, is in some respects the most important document in terms of discrediting the TV confessions in Iran. Over the last 40 years Revolutionary Courts have used forced confessions by political prisoners and prisoners of conscience as crucial evidence to prove the charges against them and to convince public opinion to side with the regime. Against this background, the testimony of Mazyar Ebrahimi about what he has been through has special significance.

This testimony, of course, will not change how the intelligence agencies of the Islamic Republic or its justice system operate, but it can change how the public views TV confessions. Ebrahimi himself says that even after it was proven that he was not guilty and he was released, a number of his friends and relatives refused to talk to him or to return his calls.

A Long History of Confessions

The history of what today is called TV confessions goes back to the early 1960s, before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. At the time, these confessions were referred to as “expressing remorse.” In 1971, Parviz Nikkhah confessed on TV to plotting to assassinate the Shah. In 1973 it was the turn of poet and novelist Reza Baraheni, and a year later the writer Gholam Hossein Saedi appeared on TV to confess. Then, in 1977, a show trial of 66 political prisoners was broadcast on Iranian National TV.

The Islamic Revolutionaries, however, showed great affinity for forced TV confessions soon after the victory of the Islamic Revolution and, over the last 40 years, this affinity has become an integral part of the judicial process for condemning political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, regardless of which political faction controls the security establishment, the justice system or the IRIB.

During interrogations, even before being indicted and tried, the accused are forced to confess against themselves or against persons named by the interrogators, either to end physical and mental torture or in response to threats against their families and loved ones. Early after the revolution — in addition to the TV confessions of Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, a one-time close associate of Ayatollah Khomeini, who was executed in 1982 for plotting to assassinate the founder of the Islamic Republic — one of the most prominent figures forced to repent and confess on TV was Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari who before the revolution was considered the highest authority on Shia Islam.

Early after the revolution, the confessions the interrogators wanted to extract under torture were usually, but not always, about the organizational connections of the detainees, addresses of safe houses and betraying the names of other members of underground cells. However, as the historian Ervand Abrahamian writes, after the spring of 1981, the main goal for those using torture was no longer to extract information or confessions against the detainee himself, but to destroy the character of the prisoner — and change his identity [Persian link]. Authorities wanted the accused to repent and prove their repentance by actively cooperating with the Islamic Republic and to even participate in the execution of their former comrades. No opposition group was immune to this treatment. In other words, TV confessions were broadcast to show the legitimacy of the government ideology and the illegitimacy of any opposition’s political beliefs and ideologies.

Two Additional Goals

After the end of the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war and the mass executions of political prisoners in 1988, from the early 1990s to this day, the security and intelligence agencies of the Islamic Republic have used forced TV confessions with two goals in mind, in addition to proving the guilt of the accused.

Their first goal is to prove their own efficiency in dealing with real security threats. After any terrorist attack, the security establishment is expected to catch those responsible. A look at the trials of “security defendants” over the last 30 years shows that the Islamic Republic’s security agencies have failed to provide convincing evidence to prove the guilt of defendants whom they have accused of crimes against national security. Torture, forging documents, denying defendants from choosing their own lawyers and, in general, violating the due process of law, reveal the security establishment’s incompetence in finding the real culprits. As a result, obtaining forced confessions and broadcasting them on TV is one way to claim that these security agencies are efficient and can successfully deal with security threats.

The second goal is to use these TV confessions to prove conspiracy theories that, at a certain point in time, agree with the views of the Supreme Leader, the strategic positions of the Islamic Republic or what it views as its current interests. And these views, positions and interests are subject to change. During the eight-year presidency of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani from 1989 to 1997, it was his views and demands that in some cases defined security initiatives and an integral part of these projects were extracting forced confessions that fit the scenarios written by security officials. It must be noted that a number of TV confessions in the 1980s also fall into this category. One example is the confessions of Mohammad Ali Amouei, a former member of the communist Tudeh Party, in 1988 [Persian video].

TV confessions by the poet and journalist Ali-Akbar Saeedi Sirjani, who died in prison in 1994 under mysterious circumstances, by the politician and former minister Ezzatolah Sahabi and by the writer Gholam Hossein Mirza Saleh in 1976 [Persian video] were also made with this second goal in mind.

Later, in the first half of the 2000s, the conspiracy theory goal was drove the TV confessions of the dissident clergyman Hossein Kazemeyni Boroujerdi [Persian video], the student activist Ali Afshari and dual national academics Kian Tajbakhsh, Haleh Esfandiari and Ramin Jahanbegloo, who were accused of spying. In the second half of the 2000s, TV confessions by members of the Green Movement and Iranian journalists reporting for foreign media, especially in the aftermath of the disputed 2009 presidential election, served the same goal.

But the TV confessions of defendants accused of assassinating Iranian nuclear scientists were meant to prove that the intelligence ministry was efficient in confronting real security threats. When the security establishment failed to find the real people responsible for the assassination of four Iranian nuclear scientists, it was inevitable that they would write and carry out a scenario to implicate suitable individuals. And this scenario included 14 other victims in addition to Mazyar Ebrahimi, who had a business office in Sulaymaniyah, a city in Iraqi Kurdistan. Some of the victims had also visited Iraqi Kurdistan for various reasons but, apart from Ebrahimi and some of his relatives who spent a long time in prison, almost all the other detainees had one thing in common: they either knew or worked with Ms. Maryam Zargar, a main defendant in the case.

In the second part of this exclusive, we will publish the complete text of IranWire’s interview with Mazyar Ebrahimi and what he and his codefendants went through during the 26 months that they were in prison.

At the end of his interview, Mazyar Ebrahimi repeats that he’s going to ask companies that supply equipment to the Iranian state TV not to sell their products to them. “These audio-visual products are used for exerting torture and it would be wrong for these companies to have any transactions with Iranian state TV,” he said.

Ebrahimi has provided a list of companies whose products are used by the Iranian government, which is published below. IranWire understands that none of the companies have any official representatives in Iran and do not knowingly sell their products to Iranian state TV or other institutions. Nonetheless, according to Mazyar Ebrahimi and many other TV professionals inside Iran, the equipment manufactured by the companies listed below are purchased through dealers in the Middle East and southeast Asia and are widely used in Iran. In the next few days, IranWire will contact the companies so that they have the opportunity to comment on the use of their products by Iranian state TV and are able to reply to Ebrahimi’s request to boycott Iranian state TV and its international branches, including Press TV (the English channel), Al Alam (the Arabic channel), Hispan TV (the Spanish channel) and Ofogh TV (the Persian satellite channel).

Sennheiser, German sound equipment manufacturer

Arri, German camera manufacturer

Grass Valley, a Canadian company owned by Belden, a US company

Dedolight, a German light equipment company

Kinoflo, an American light equipment company

Panther, a German grip equipment company

Barco, a Belgian television and screening equipment company

Neumann, a German sound equipment company

Neutrik, a Lichtenstein-based company selling audio and video equipment

Shure, an American sound and microphone manufacturer

Anton Bauer, an American battery manufacturer, part of the British ViTec Group

Ross Video, a Canadian live event equipment and video production company

Thomson Video Networks, a French company specializing in video compression and transcoding

TekTronix, an American electronic company

Wohler, a German monitoring and camera company

XiCom, an American IT consulting company

Manfrotto, an Italian tripod manufacturer

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments