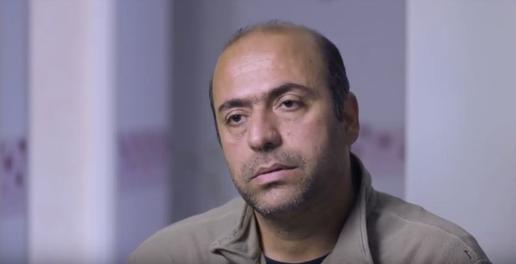

Darius, aged 45, is thought to be the oldest Iranian refugee in Calais. He has been on the road since 1997, attempting to reach the United Kingdom.

He now lives alone, detached from friends, family, and other refugees. Two decades of asylum-seeking have taken a heavy toll.

“Neither Iran nor France is a place to live,” he tells IranWire. “During all these years, I lost my pride, character, family, and home. And what did I get in return? Nothing.”

Many other older refugees feel the same way as him, he says, and struggle with physical and mental difficulties. “Living in Europe is not worth wasting your youth.”

Darius is a tall man with tanned skin, and who speaks with a calm voice in an accent from southern Iran. He was 24 when he left Iran and had his whole life ahead of him.

All he was looking for was a place that he could “feel free” and “breathe,” he says.

He applied for asylum in Germany, and then Switzerland, but he was rejected in both cases. He then decided to travel to Calais to try his luck reaching the UK.

Now, after living on the streets and in the Calais Jungle for several years, he has decided to stay in France for the sake of his seven-year-old son. “I never wanted to stay in France,” he says. “I never liked it and I still don’t like it now. But I feel like I have no other option.”

“Always Ready to Run”

Darius reached Calais in 2004 and began living on the streets with 50 other Iranian refugees. At first he lived near the port, but later moved to the woodland.

Every night, the refugees would try different ways to make it across the Channel. At the beginning, when the coastguards were less active, they would sometimes swim for 50 meters to reach a ship. This method, reportedly invented by the Iranians, was often successful. Many of Darius’s friends made it to the UK this way.

Darius, however, did not. For him, life on the streets became harder every day. Living rough meant “always having your shoes on, sleeping with one eye open, and always being ready to run,” he says. It meant being awoken by police batons and tear gas, having your possessions thrown in the sea, being assaulted, being arrested.

It meant not having access to basic medical and sanitary needs, and being vulnerable to physical and mental illnesses.

“Many years of my life were wasted just trying to avoid being caught,” he says. “This is the case even today.”

No Honor or Morality

No matter how long you have been in Calais, life looks the same. Days are spent waiting for food and clothes donations, while nights are spent trying to avoid the police. It is a difficult, stressful life, and fights are common. Police rarely intercede – especially if the brawl is between refugees and traffickers.

“In this life, there is no sign of honor or morality,” Darius says. “Especially among traffickers.”

Traffickers are known to rape and murder their clients, or force them into prostitution. But few people are sympathetic to refugees abused in this way, Darius says.

“Here, ordinary citizens often snitch us out to the police. Many refugees get hit by cars and die crossing the highways outside the Jungle. Some of them are intentional hit-and-runs.”

Asylum seekers often try to reach their target country by clinging to the axles of trucks. But this method is extremely dangerous, and many people fall and are crushed to death under the wheels. Darius tried to escape Calais by truck several times, but was never successful. Sometimes he ended up in the wrong place, other times he was arrested. On one occasion, he became trapped and almost suffocated, but managed to notify the driver and get out just in time.

After failing to make it to the UK by himself, he paid traffickers to help him. But they always disappeared after he had paid them the money.

Meaningless Deaths

Calais is full of Iranian traffickers, from small-scale dealers to members of major human trafficking networks. “Wherever there is a client, there are traffickers as well,” Darius says. “I saw travelers that got to the UK with €20 (US$22) or even a pack of cigarettes as a form of payment.

“You usually can tell a trafficker’s personality the first time you meet and talk with them.”

At one time, Darius was a part of a trafficking network. He used to rob food trucks to steal food for refugees and says his nickname was “Robin Hood.”

One trafficker, Saeed, was a friend of his. He was arrested in 2004 along with several other members of the operation after two Iranian refugees reportedly made a deal with the police.

He died in prison, but it was never revealed whether he was murdered or committed suicide.

Darius tried to get his friend’s body transported back to Iran, but was unsuccessful. “I called the Iranian embassy and told them he had died. They said, ‘So what?’ They did not accept him as an Iranian citizen since he did not have his ID on him. They told me just to call his family and let them know their son is gone.”

Mask of Humanity

In 2016, after the terrorist attacks in France, the government ordered a shutdown of refugee camps in Calais.

The camps had been set up by volunteer groups in 2014 and had developed into small communities. They even shared a church, mosque, and a restaurant.

The refugees were sent to other cities across the country, but almost all of them returned to Calais. Returning was easy, as security was lax and few support services were provided.

“The least the French government could do is to treat refugees with respect and humanity,” Darius says. “Or else they should get rid of the human rights mask they have on and stop pretending that France is the ‘land of refugees.’”

He adds: “The same day that they gave citizenship to a refugee who saved a boy hanging from a building, they shut down all the refugee camps in the north of the country.

“This is the same trick we experienced with the mullahs in Iran.”

A Life of Displacement

Darius has lived the rootless life of a migrant ever since he was young. He was born in Abadan, and the war between Iraq and Iran began when he was a young child. At the time, his father was working on the oil wells in the south of the country. Left alone, his mother decided to take the children to Shiraz, along with other war-torn families.

But the family never felt wanted there, Darius says. “At one point, they shut down the water on us, and the Friday prayer’s Imam said that we Abadanians had made everyone’s lives worse. He said that if we were real men, we would have stayed in our city to defend the country.”

But Darius had already lost two brothers that decade, he says. One was a member of the Communist Party, who was executed by the Islamic Republic, and the other was killed while working at a military base in the south of Iran.

“One day they sent us his lifeless body, which was covered in scars and marks from being beaten,” Darius says about his brother who worked at the military base. “When my family asked the reason for his death, they replied: ‘Don’t ask any more questions if you want to save your other children.’”

His family was eventually forced to move to Tehran to live in the shelters the government provided for people displaced by war. But the conditions were very hard there, so they moved again to Isfahan. They lived there, alongside many other war-torn families, until the end of the war.

“When the war ended, Khomeini ordered that we should be evicted. Living under those circumstances made me hate the regime forever. I decided to leave the country to be able to breathe. Since I did not have a passport, I paid for a fake one to leave Iran.”

“Ugly, Dark and Negative”

A man called Bakhshandeh in Ferdowsi Square in Tehran made Darius a fake passport and helped him reach Moscow. From there, he made it to Kiev, Ukraine.

Darius hoped to reach Germany, but the first traffickers he paid robbed him of his money. His next attempt was successful, but Germany then rejected his application for asylum. “After that, I headed for Calais,” he says. “I was hearing about the UK from everyone on my journey, and I was hoping to pursue my education in chemistry and make a good life for myself. Instead, I lost everything.”

If he could go back and do it all again, he would still leave Iran, he says, but “not in the same way” he did before. “I don’t have any desire to go back to Iran. The meaning of home for me was my parents, but I lost both of them during the years I’ve been away.”

If he knew what he knew now, he adds, he would not stay in Calais. “I experienced too many difficulties there over the last few years. It wasn’t worth it in the end.”

Now he has been living in Calais for many years and describes his experience of asylum-seeking as “ugly, dark, and negative.”

“If only I had enough money, I would go far away to live my life alone, in peace,” he says. “That is all I have ever wanted.”

Read other articles in the series:

Rape and Sexual Abuse is Common

“I left Iran so my daughter could choose her own destiny”

One Man’s Story of Life and Smuggling in Baluchistan

“A Long Journey to Turkey — to Save my Mother”

"The Biggest Torture Was Losing my Identity”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments