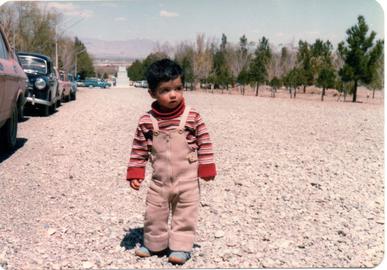

Two weeks ago, on a day like every other day, Beygom’s 11-year-old son Zabih left their home in Alaein in the borough of Rey, a town near Tehran, to sell a ragbag of goods — a few pairs of jeans, women’s stockings, washcloths and a pack of colorful hairpins. As usual, he headed toward the metro station.

He has not been seen since.

Beygom is an illegal immigrant from Afghanistan. In addition to Zabih, she has five other children, and none of them have a residency permit. Her husband works at a small slaughterhouse on the outskirts of Rey; since he has no residency permit his pay is one-third of what other workers receive. When he returns from work, Beygom takes the children out of their 24-square-meter room so that her husband can rest for a few hours before returning to work.

I ask her about Zabih, but she is not worried about him. “This is not the first time that this has happened,” she says. “He can take care of himself and he will be back home sooner or later.”

Last year, when a so-called “project to collect street children and child laborers” was being carried out, Zabih was apprehended and had to spend a week in a camp called Tobacco Gorge. The people who picked him up asked him to phone his parents or to give their address to camp officials and promised to return him to his home, but Zabih feared that they would deport his parents so he didn’t give them his real name or his address. As a result, they deported him to Afghanistan at the Taybad border crossing in Razavi Khorasan province. A month later, his uncle’s family helped him to illegally cross back into Iran.

Now the same project under a slightly different name — “the project to bring order to child laborers and street children ” — is underway and Zabih has disappeared again.

The resumption of the project, which started on June 12 in Tehran and other big cities, has prompted protests from children’s rights activists. They believe that the initiative, which has been ongoing for years, has not only not produced favorable results but has done harm — the quarantine camps authorities take the children to have dismal conditions, and they shave the children’s heads and humiliate them. After this, most of the children quickly return to the merciless cycle of work.

“These children are arrested and taken to quarantine centers as part of a stressful and tense process and spend a painful time in an unsuitable environment,” a statement by the Child Labor Assistance Network, one of the most important campaigns for children’s rights in Iran, announced. “Sometimes they are deprived of the right to contact their parents and relatives and sometimes, like prisoners, they can only leave their rooms and go outside into the yard for a couple of hours. These centers often make their physical and psychological pains worse. Afterward they are returned to the same situation as before.”

The statement also refers to the deportation of child laborers of Afghan origin to Afghanistan. “We hear reports of Afghan child laborers being deported across the border,” the statement says. “This is a clear violation of the principle of not returning refugees and asylum seekers under international norms.”

Changing the Question instead of Finding a Solution

Omid Chalak is a university student who volunteers his time to teach reading and writing to child laborers. He says he has seen firsthand the negative impact of this project on the lives of child laborers, calling it a naked violation of the rights of children, and an attempt to change the question instead of providing a solution. “Once in a while, these gentlemen attempt to hide the manifestations of poverty for which the officials are directly at fault,” he says. “So they try to sweep the trash under the rug so as to present a cleaner image of the city. But since they have made no plans to solve the fundamental problems, these manifestations of poverty return soon enough. The only result is the expenditure of a lot of money that could have been spent on the education of these children and on alleviating their poverty.”

A considerable amount of money has been spent on the project since its inception in 2005. Child laborers are rounded up in the streets by police vans, taken to holding centers such as the Yaser Children Safekeeping Center and released back to the streets a few days later. The Yaser Center was designed with a small capacity for 35 children — and yet currently it caters for more than 150. Photographs of the center posted on social media have prompted angry reactions.

Hadi Shariati, the deputy president of the Society for Supporting Children’s Rights, told the Iranian Labor News Agency (ILNA) that “the project to bring order to child laborers” has no other goal apart from the removal of child laborers from the streets — what happens to the children after they are removed from the streets is not part of its brief.

Figures provided by the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor and Social Welfare show that despite the initiative, not only has the number of child laborers not dropped, it has actually increased rapidly, so much so that between 2015 and 2017 it rose by 21 percent.

According to Habibollah Masoudi-Farid, Iran’s Welfare Organization’s Deputy President for Social Affairs, 53 percent of these children have no identification documents of any kind. And many officials have pointed out that a considerable number of them are not Iranian citizens and have illegally crossed the border into Iran. Some officials even claim they have been sent to Iran to panhandle as part of an organized scheme to make money — a sort of “investment.”

Distorting Statistics

Anooshirvan Mohseni Bandpey, Tehran’s provincial governor, has claimed that 82 percent of street children and child laborers are foreign nationals. However, two years ago, after analyzing the statistics regarding these children, an associate professor at the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation told Tasnim news agency that 59 percent of them were Iranians and only 36 percent were Afghans.

Dr. Feriyal Azari, a children’s rights activist in Iran, told IranWire that when Afghan child laborers are picked up by authorities and do not have a residency permit card, they are sent to the Tobacco Gorge camp in the Afsariyeh neighborhood in southeastern Tehran. “They take their money, their mobile phones and their belongings,” she says, “and sometimes they send them to Taybad border crossing without informing their parents.” She says they don’t allow them time to arrange for their families to meet them as the cross the border back to Afghanistan.

Most families of Afghan children who work on the streets know where to look for them when they do not return home after a few days, Dr Azari says. “Some of them go to Tobacco Gorge to look for them. But some are forced to sit on their hands because they lack residency documents. After the children are held in the camp in an unhygienic environment for a few days, they load them onto decrepit minibuses, take them to Taybad border crossing through Mashhad and abandon them there.”

Some children do have residency permits but are not carrying them when they are picked up. “But,” she says, “a few days in an unhygienic environment passes before they can prove that they are here legally. The parents are contacted so that they can bring the documents and take away their children. But a lot of times the phones and the meager money belonging to these children are lost in the shuffle and they have to return to point zero in the streets, and in unhappy mental conditions.”

Dr. Azari talks about one child who had been brought to Iran by his uncle after the death of his parents in Afghanistan. “He was only nine,” she says. “I met him at a school where I go to help immigrant children. His uncle abandoned him when he lost his job and the child had to provide for himself on the streets. He had nobody and slept under bridges.”

Yet, in an effort to give Tehran and other big cities a makeover, authorities clear these children from the streets, load them onto decrepit minibuses and discharge them on the other side of the border, where the chances are high that nobody is waiting for them.

Related Coverage:

Smuggled Afghan Children Working as Street Peddlers, February 20, 2019

The Story of an Afghan Boy Trying to get to Iran, December 14, 2018

Who are the Main Victims of Human Trafficking in Iran?, July 23, 2018

Human Trafficking and Iranian Law, July 21, 2018

Why Is Iran the Chosen Pathway for Human Traffickers?, July 16, 2018

Child Trafficking by the Truckload, July 7, 2018

Wasted Youth: The Hidden Trash Collectors of Tehran, December 2, 2014

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments