Why has Iran’s judiciary been unable to gain public trust over the last 40 years? What are the basic problems of the institution, the original primary goals of which were to"litigate, protect public rights and implement justice" in order to "uphold individual and social rights”?

In this series, IranWire will look at the structural problems of the judicial branch of government, relying on concrete examples and statements from legal experts to build a picture of the judiciary and whether it functions according to the principles on which it was originally based.

In the first part of the series, IranWire looked at the independence and impartiality of Iran’s judiciary. The second article looked at the protracted trial process, which successive judiciary heads have promised to reform, without success. The third article addresses corruption in the judiciary.

In the fourth article in the series, IranWire looks at the way judges are appointed and the training they receive, and examines how this contributes to Iran’s corrupt and flawed judiciary.

**

In most countries, becoming a judge is a challenging task. In France, judges are graduates of law schools and study to postgraduate level. In the United States, a legal professional has to gain years of experience as a lawyer before becoming a judge. In the United Kingdom, a law graduate must have gained between five and seven years of experience as an attorney, teacher or researcher in the field of jurisprudence. Only then can he or she put themselves forward as a judge.

In Iran, a high number of judges who worked on important cases relating to dissidents since the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the establishment of the Islamic Republic do not have legal expertise or academic education in the field of jurisprudence.

Iranian writer and human rights activist Iraj Mesdaghi says that Judge Abolghasem Salavati, who has become world-famous for his record of issuing death sentences and imprisoning numerous dissidents over the years, became a judge without even having a degree in law or any judicial expertise.

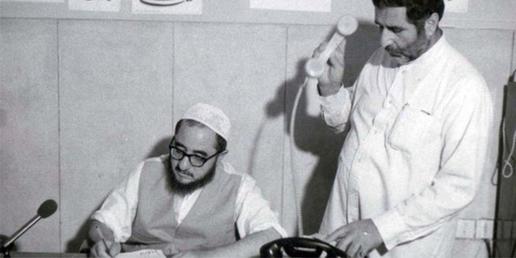

Asadollah Lajevardi, a former revolutionary prosecutor and a key official overseeing Evin Prison, handed down death sentences for thousands of political prisoners in the 1980s, including rulings that led to the mass execution of prisoners in 1988. Many of them were members of the People’s Mojahedin Party (MEK), and he was later assassinated by this group in the late 1990s. Lajevardi is said to have dropped out of high school during his second year and studied theology. He had no specialization in the law or judiciary matters.

Mohammad Moghiseh, the head of Branch 28 of the General and Revolutionary Court of Tehran, also secured a role as a judge without a university degree, and his training comes from religious seminaries.

These conditions apply to most officials in the judiciary, at both lower and senior levels.

Mohammad Sadegh Khalkhali, another famous religious judge, also issued death sentences for numerous dissidents following the 1979 revolution. He was responsible for the execution of a number of pro-Shah former military leaders, including General Nematollah Nasiri, General Mehdi Rahimi, General Reza Naji, and General Manouchehr Khosrodad, among others. Sadegh Khalkhali studied in academic schools up to the sixth grade, and was then sent to the religious seminaries of Ardabil and Qom. He never studied for a law or other relevant degree.

How are Judges Selected Today?

Today, men — it is only men, as women are not permitted to be judges in the Islamic Republic — are usually appointed as judges after taking an exam, and information about the exams can be found in a publication produced by the judiciary's human resources department. Those sitting the exams must be experts in law, jurisprudence, and theology with a focus on jurisprudence and the basics of Islamic law, and they must have a Master's degree in Islamic sciences, or be a seminary level-two graduate.

As part of their preparation for the exam, judge hopefuls study jurisprudential and Islamic texts, civil law, commercial law, civil procedure, criminal procedure, and criminal Law. Candidates who pass the test stage are then tested on their character and suitability for the role.

The character assessment stage is in two parts. The formal test and the character assessment, which includes an in-person interview and an evaluation of the individual’s ideological make-up, are looked at together to determine whether the candidate is suitable to be a judge in the courts of the Islamic Republic.

What Happens at the Character Assessment Stage?

Alireza Mabani, an Iranian doctoral student at the University of Santa Clara in California, says that ever since he was a teenager, he has dreamed of presiding over a court. He says he believes judges can play a redemptive role in people's lives.

In Iran, Mabani was a good student at school and did well at most subjects. When he decided to study humanities instead of medicine or engineering, he faced serious opposition from his father. Despite this, Mabani pursued his studies in law, and achieved high grades at a leading university for the subject. He took the judge exam twice, but failed both times at the character stage, despite securing a good score in the written test.

Mabani last took the test in 2017. Afterward, he decided he would have to leave Iran to realize his dream.

He says when he went through the character assessment stage he was asked a number of questions including: "Do you pray? What was the most important aspect of the battle of Tabuk? How is the tayammum ritual [purification using purified sand or dust without any water] performed? What are the aims of the Quds Day march? Can you provide examples of eyak nabodo and eyak nasta'in [Quran verses read in prayers]? Do you consider the Supreme Leader a popular figure? What is the difference between a source of emulation and Velayat-e-Faqih? Who are Talha and Zubair? When your sister goes outside the house, does she wear a chador or a veil with a manteau and pants? What is your view of the principle of Velayat-e Faqih? Who did you vote for in the last presidential election? What do you think about the performance of the previous governments and the current one?"

Alireza Mabani had answered the evaluator's questions with the utmost honesty, but when he left the room, he realized his mistake. A person who had passed the character or personality test had told him that he should not have expressed his opinion at all, that he should have pretended he had voted "out of duty" and cast a blank vote. He should not have expressed any opinion about the government, the JCPOA [the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the nuclear deal], or anything else.

The exam authorities later conducted an investigation into Mabani, asking local people if they had seen him attending congregational prayers. Does he practice the principle of working for good and prohibiting vice? they asked. Is he a member of the local Basij, the volunteer wing of the Revolutionary Guards? Do the women in his household wear hijab properly? Has he been seen interacting with the opposite sex on the street? They asked similar questions that had nothing to do with the practice of judging a case, arbitration, or anything else relevant to being a judge. He says he still does not understand the connection between his views on the nuclear deal and making decisions in a courtroom.

Musa Barzin Khalifehloo, an Iranian lawyer now based in Turkey, had similar experiences. "When assessing a candidate for the judiciary, there are political and ideological interviews and local investigations into how the candidate's family dresses and what they believe, including investigations into who he voted for in the elections and whether he participates in Friday prayers or not, whether he is a member of the Basij or not, and to what degree he accepts Velayat-e Faqih.”

Barzin Khalifehloo says this approach is upheld in Iranian law. Relevant laws and regulations for the recruitment of candidates for the judiciary set out that ideological issues and political affiliation play a more important role than academic achievements, experience or other aspects. "Judges are usually selected from the clergy and graduates of institutions affiliated with the government, including seminaries, Razavi University, Imam Sadegh University, and the University of Judicial Sciences. Only a very small percentage of judges are selected out of law graduates from ordinary universities."

Mohammad Olyaeifard, an Iranian lawyer now based in Canada, outlines the lack of independence in the selection process for judges. "The head of the judiciary is appointed by the Supreme Leader; this means he is the grand cadi [the judge of the judges] of the judiciary and delegates the responsibility of the grand cadi to the head of the judiciary. For this reason, the head of the judiciary conducts his work in a biased way and in line with the Leader and his entourage. On the other hand, according to the Constitution, one of the head of the judiciary’s duties is to hire fair judges. So when we talk about the employment of fair judges, it should mean that after the appointment of a judge, the judge must forget the head of the judiciary, the leadership, or any factional and political affiliation, and judge cases with fairness and impartially. But this does not happen, and the judges act in a biased manner. To support this claim, I must say that the text of the judges' oath also states that the judges swear to follow the instructions of Velayat-e Faqih [Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist]."

In the process of hiring a judge, what is important is his political and ideological orientation rather than his ability, intelligence, education, and professional and scientific qualifications.

A lawyer based in Khuzestan told IranWire: "A large percentage of the judges I dealt with were illiterate and inexperienced. A few years ago, it was said that officials would identify and replace illiterate judges. But since then there has not been any news about this. How can an esteemed judge, who graduated from a seminary, who has three obvious misspellings in a short sentence he has written and does know about simple civil matters and general law behave fairly in a complex case? Most judges who come from the seminary do not have the necessary expertise and are more of a preacher, a chaplain, or a representative of the religion than a judge."

The lawyer says the only solution to this pervasive problem is to reform the way judges are recruited and hired. "Judges should be recruited by the judicial system, not the clergy. They must have graduated from specialist judicial universities and not from the seminaries. Resolving people's cases does not require rhetoric . It requires expertise."

Musa Barzin Khalifehloo says the recruitment system is not just inefficient, it is corrupt "It is in the light of this lack of attention to the expertise of the judge that we hear, for example, that 126 corrupt judges or another 56 corrupt judges have been fired."

When hiring a judge, he says, instead of paying attention to specialist training, those in charge of deciding who will be a judge ask the candidate’s neighbors and other people about whether they pray or fast, and about what kind of family they have. They look to see if the applicant is left or right leaning. When I was a student, during the presidency of Mohammad Khatami, I heard these authorities ask the judges what they thought about Khatami's presidency. If they said it was good, they were trapped, and if they said it was bad, they were also trapped. The only way out of this was to say: I have no idea."

According to Barzin Khalifalou, the Iranian regime does not want a judge to be an investigator, a researcher or a questioner: "Of course, this does not mean that all judges are like that. We have also had extremely good judges who have been able to cleverly cross the barrier of these strange vetting process and chosen the path of serving the people. But the reality is that the prevailing system means judges are not selected on the basis of academic merit, ability to discern, and judgment."

According to Article 158 of the Constitution, it is the head of the judiciary’s duty to recruit fair and competent judges, dismiss or appoint them, change their location of service, determine what specific roles they take on, and promote them.

"In democracies, the selection of a judge is based on a strict system of hiring impartial and appropriate people,” says Hossein Raeisi, another Iranian lawyer now based in Canada. The health of the judiciary’s structure is based on the health of the judge. But in the judiciary of the Islamic Republic, especially after the revision of the Constitution in 1989, the main problem is that the judiciary has become an institution with a top-down hierarchy. At the top of the pyramid is the head of the judiciary, who is the grand cadi. He has vast and unlimited powers and those below him in rank fear him, and have a kind of unlimited obedience. At the same time, the type of training judges receive, the way they are selected and the way their performance is assessed reinforces the pyramidal view. The whole system looks upwards, which ultimately leads to obedience and corruption. Having independence in judges would means designing a system in which each judge acts as an independent and impartial person in any given situation, a man who can issue his verdict freely and without fear and without political orientation."

Raeisi believes that the independence of the judiciary would not mean that the judiciary would be independent from the executive or legislative branches. "I believe the concept of the independence of the judiciary means that each judge and every small part of the system can judge and rule between people and people, and between people and the government, and enable decisions to be completely independent and made without fear or dependence on other areas of society. Because of the absence of this principal feature, I consider the current structure of the judiciary to be a flawed one."

Read other articles in the series:

Iran’s Prolonged, Infernal Tunnel of Litigation

Is Iran’s Judiciary an Impartial and Independent Institution?

Endemic Corruption Renders Iran’s Judiciary Ineffective and Unjust

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments