A father whose son faced the death penalty took his own life because of pressure from foreign media, a lawyer working on the case for the Iranian judiciary has announced.

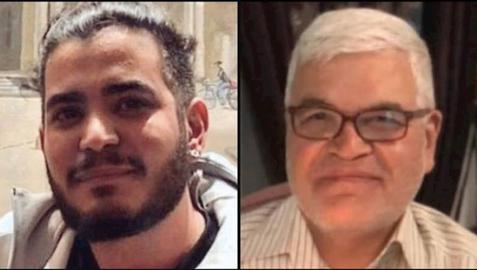

The news of Nasser Moradi’s suicide was reported on September 28. His son, Amirhossein Moradi, is one of three men who had been handed down death sentences for taking part in November 2019 protests. Although the executions have been temporarily halted, likely in response to international outcry, Iranian authorities have not provided any further information on the cases of the three men.

"We have no law prohibiting people from speaking,” Babak Paknia told Iran International in a television interview when asked whether the Moradi family had been pressured not to talk to the media. “I'm talking to you now. Has something happened to me?" Paknia represents the Iranian authorities in the case against Amirhossein Moradi, Saeed Tamjidi and Mohammad Rajabi.

Paknia told Iran International and other media that Nasser Moradi had been contacted by foreign media, prompting him to take his own life because he was under such pressure to speak about his son’s case.

Foreign media were following up on #Do_Not_Execute, the popular campaign to save the lives of and free the three protesters, which was in turn prompted by the news about the their cases.

So can it be dangerous to inform the public about cases and sentences brought against citizens? In some cases, can it cause harm, and even lead to people losing their lives?

Recent history has shown the role publicity can play in raising awareness about lawsuits against members of the public, and in particular cases involving political and civil activists, protesters and people arrested for their social media activism. Activists advocating for details of their cases to be made public have argued the importance of such campaigns, and point to examples where this has influenced the outcome of the case. They say constant updates on cases, including details about prison conditions, the health of the prisoner, and reporting on periods when prisoners have been kept in solitary confinement or tortured, has led to a reduction in the length and severity of sentences, or to prisoners being granted medical leave. The recent efforts to tell the world about the plight of the November 2019 protesters, whose lives were spared at least temporarily, is one recent example, although their cases have not been resolved.

Family members and supporters often provide information about cases, as do lawyer defending their cases. For most Iranian domestic media, reporting on the activities of the judiciary is a red line they dare not cross for fear of serious reprisals. Sometimes these media go to the families and their lawyers for information. Even if the family is hesitant to give an interview, it will usually provide some sort of information about the case. Certainly, this is the approach of Persian-language media outside Iran.

However, Iran’s security forces routinely put pressure on families to keep quiet, often making false promises or threatening them, so that no information about the case is reported in the media, including social networks.

For years, these judicial and security agencies have summoned, threatened, detained, and imprisoned anyone who disseminates information about a prisoner other than what has been said in an official capacity. This illegal behavior is carried out under the guise of fighting "propaganda against the regime" and "conspiracy against national security.” Occasionally, the lawyer on the case also recommends to his or her client and their families not to speak to the media, believing that remaining might be more advantageous for the case and the defendants. However, sometimes lawyers who give this advice are appointed by the court. Since they are not independent, this advice to remain quiet might not actually benefit the prisoner.

A Step Too Far

"It is not a question of talking to foreign media,” Sadegh Larijani, the former head of Iran's judiciary, said in February 2010. “The main issue is that some lawyers, instead of working for the rights of their clients, challenge the judicial and political system of the country, a step too far that doesn’t help their clients. They should be held accountable for what they say."

In February 2010, attorneys Nasrin Sotoudeh and Mohammad Olyaeifard were imprisoned after they spoke publicly about the cases of their clients, who had been sentenced to death.

Ten years on, the new head of the judiciary, Ebrahim Raeesi, has followed in Larijani's footsteps, upholding the same judicial procedures as his predecessor. If a lawyer or another person, especially someone who does not appear to adhere to the same perceived values as the judiciary and the Islamic Republic, "damages the system" with his or her comments, they will have to pay for it.

Babak Paknia’s comments suggest that, under the Islamic Penal Code, it is actually a crime for Iranians to speak to foreign media, and give them on-the-record interviews.

"A person who talks to domestic or foreign media has not committed a crime,” lawyer Musa Barzin Khalifelou tells Journalism is Not a Crime, IranWire’s affiliate site. “There are no restrictions in law regarding interviews with the media. Even giving interviews to the media of a country with which Iran is at war is not a problem. Anybody can even give an interview from inside the country on Israeli state television, and there is no legal ban on it."

Speaking to the Media is not a Crime

So why is it that so many people are arrested for speaking to the media? How can they be tried and sent to prison on such a charge? Shahnaz Akmali, the mother of Mustafa Karimbeigi, who was killed during the Ashura protests in December 2009 following the disputed presidential election earlier that years, responded to Babak Paknia's recent remarks. She was herself arrested after she drew attention to her son’s case, so her reaction to Paknia was strong: She published a photograph of her court documents online, an image that clearly states that the court had cited her interviews with media outlets such as the BBC, Manoto and others as charges against her.

"Mr. Paknia, this is some of what I was accused of,” she wrote on Twitter. “It clearly states that one of my crimes is links with foreign media, informing people about my son's death and helping other prisoners. How can you say in your interview with Iran International that giving interviews to the media is not a crime!"

Akmali was one of many who was arrested after she gave interviews. In fact, a review of the judiciary’s record over the last three decades makes it clear that giving interviews to the so-called dissident media has led to long-term prison sentences in many cases.

Kasra Nouri, lawyer and dervishes' rights activist, Seyyed Ali Akbar Nabavi, the father of political activist Zia Nabavi, lawyers Mohammad Najafi and Amirsalar Davoodi, political activist Sadegh Zibakalam, Baha'i citizen Abdollah Nasheri, and journalist Hassan Fathi are among the many people who have been sentenced to imprisonment and flogging in recent years for giving interviews to foreign media.

Lawyer Musa Barzin was sentenced in 2011 to three months and a day in prison for giving an interview to Persian-language media outside Iran. "I was giving interviews to Iranian media abroad, such as Radio Farda, to inform them about the status of my clients' cases. A case was filed against me on charges of 'propaganda against the regime.' Giving interviews with enemy media about defendants who had appeared before revolutionary courts was listed in my indictment."

Barzin explains how the judiciary can justify such behavior. "From the point of view of the legal authorities, the person may have stated in his interview examples of crimes. So then, according to the law, the person has committed a crime by doing this. Insulting, spreading lies with the intention of disturbing the public mind, and propaganda against the regime are among the crimes people are accused of when they give interviews with Persian-language media abroad talking about their court cases. In human rights cases, most people are accused of propaganda against the regime and of collaborating with hostile states.”

A Fake Theory to Scare Families

On Sunday, September 27, Nasser Moradi, Amirhossein Moradi's father, hanged himself in the basement of his house. Although the #Do_Not_Execute campaign put a temporary stop to Moradi’s death sentence being carried out, along with the sentences against Saeed Tamjidi and Mohammad Rajabi, their sentences had been held up in the appeals court, and the uncertainty around their cases was thought to be a source of distress for Nasser Moradi.

A day later, the lawyer working on the case against them blamed the foreign media for the suicide. The news was reported on pro-government websites, including Mashregh News, and other Iranian media. A video reporting the news was also broadcast by the BBC Persian Service. Babak Paknia repeated his theory about Moradi facing pressure from the foreign media in an interview with Tasnim news agency on Tuesday, September 29, as well as on Iran International television.

"As a person involved in this case, I say both the media inside the country and the opposition media outlets abroad caused Amirhossein's father to commit suicide,” he stated with confidence. In addition to his apparent shock that anyone could think defendants or their families would be prevented from talking about their cases, he then appeared to adopt an empathetic approach. “Families can also talk. It was our recommendation, as lawyers of the case, that the families should not give interviews because they would not feel up to it.” His statements met with criticism and anger on social media.

Speaking to Journalism is Not a Crime, lawyer Musa Barzin Khalifehloo says families should try to resist pressure not to speak to the media, or to any other demands authorities make, since this could have a negative impact on the case. In his view, it is safer to make the public aware of the details of the case.

"Security forces tell all families not to give interviews,” he says. “In my opinion, families must inform the people about the status of the case; in general, doing interviews is better than silence. These interviews and these reports will definitely be better for both the family and the loved one who is in prison.

"If families do not want to be interviewed, they can try to provide information to the media in an alternative way," he suggests. "The media is also obliged to be cautious in such cases and to publish news quoting an informed source. If this happens, it will make it more difficult for security agencies to pressure the defendant's family after they give an interview.”

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments