The term "home quarantine" has now been added to the daily vocabulary of people around the world. Authorities in cities and countries around the world have required people to stay home to fight the deadly coronavirus disease by limiting its spread. Until a few months ago, coronavirus was not in common vocabulary, and many were looking for an opportunity to catch up on their work and lives; a time to relax, a time to watch movies and TV series, an hour to study, even a chance to tidy up a room in the house. But now many people are not satisfied with these opportunities, are not enjoying themselves, and want to return to normal as soon as possible.

Compulsory lockdowns and the unclear end date for this period of enforced relaxation also make many people compare the experience to time in prison. Some speak of depression and despair, and others go a step further and compare quarantine with solitary confinement. IranWire has spoken with people who have experienced true solitary confinement, in prisons, asking them about the similarities and differences between quarantine and solitary confinement.

Most people who have experienced prison and solitary confinement do not find it comparable to home quarantine. But the strategies they used to maintain their morale in those difficult days are likely to serve as a source of relief for those who are frustrated and despairing today.

****

“Those who compare home quarantine because of the coronavirus to prison and solitary confinement probably are just not aware of what solitary confinement and prison is. Prison or solitary confinement is where you are held against your will; in quarantine, you decide to stay at your own home or wherever you are, of your own accord. The solitary confinement cell is something I hope no one will experience.”

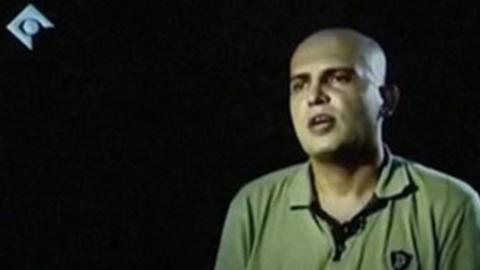

Mazyar Ebrahimi, unjustly charged with the assassination of Iranian nuclear scientists, was imprisoned for 26 months, from June 13, 2012, to July 27, 2014. He spent 16 months of this period in solitary confinement and was subjected to physical and psychological torture for the first seven months. During those 16 months of solitary confinement, Ebrahimi neither met anyone nor had the right to make phone calls.

Having no vision of an end to the coronavirus pandemic, being obliged to stay inside the four walls of one’s home, engaging in home-based exercise, physically avoiding family members, and even spending Iranian New Year without the usual traditions because of the quarantine, may look similar to the experiences of those who have endured prison and solitary confinement. But the sufferings of political, security or religious prisoners in Iranian prisons is a testament to the substantial differences between the two realities.

Mazyar Ebrahimi is one of those who dismisses the comparison between quarantine and solitary confinement. But he also describes quarantine as an opportunity to look into one's own self; this is what happened with him in solitary confinement.

It is sometimes difficult to read and listen to the stories of Mazyar Ebrahimi and other prisoners of conscience. He, like many others in the Islamic Republic of Iran, was forced through torture to confess against himself on television. But after his release he said: "I confessed only to avoid torture and beaten with a cable. I was stretched out on a bed and they hit me with a cable as much and as hard as possible. They were laughing, saying that my feet were becoming the size of my head. I couldn't even walk on the day of my TV confession. Two guys grabbed my arms and put me on the chair in front of the camera. I had to repeat whatever they said. I had to repeat it exactly in same way. They had threatened that if I didn't say exactly the same thing, they would keep beating me, down to my bones. When my mother saw my confession on television she had a stroke. She has not still returned to her previous condition. My family didn't know where I was for 16 months.”

More than five years have passed since Mazyar Ebrahimi's release. He now lives in Germany and is adjusting to life as an asylum seeker. In the months after the coronavirus outbreak, he has spend most of his time home alone, a situation which sometimes reminds him of his solitary confinement and torture. But perhaps that violent experience has made it easier for him to go through quarantine and exile. This is why, in comparing the two, he began by emphasizing that solitary confinement is "not at all" comparable to quarantine.

"In solitary confinement, you are not in control of what you eat. Even going to the bathroom is not in your control. You have to call; someone opens the door and lets you go to the bathroom. You can't eat what you want. I remember the first day they gave me an apple, after a long time. I didn't want to eat the apple. I just smelled it and looked at it. It had become something strange to me. There was nothing special that I could do. Eventually, I would wake up in that three-by-four-meter cell and walk round and round because there was nowhere else I could walk. It was a tiny place. The guard who was watching me through the camera said he got dizzy watching me going round and round and asked me not to walk. There were no books to read, no newspapers. The only thing that can entertain you is thinking.”

Quarantine is an entirely different experience – which in Ebrahimi’s view is only a change in one’s usual habits.

"In quarantine you are not cut off from the outside world. You can go out for a walk without touching others, without approaching or shaking hands or contacting others, while wearing masks and gloves. People can step outside with one another, come back, stay with their families. They have the means of communication like smartphones, the TV, the internet. They can watch a movie, listen to the news, read a book they love and they can cook. In quarantine no one will abuse you, no one will hurt you, no one will break your hands and legs. If you have a problem you can call the emergency services. You can go to the pharmacy or supermarkets and buy what you need. I think quarantine it is a great opportunity for people to be with their families more, or if they live alone, to spend more time exploring their own inner lives. I beg everyone to think about others, not just about themselves, as we have other people in our lives.”

In those 16 months of solitary confinement, Mazyar Ebrahimi didn't even think about exercising. Although he had been advised to exercise by a health practitioner, enduring torture had demotivated him from exercising and taking care of his physical condition.

Ebrahimi said that his "innocence" was the only drive that made those difficult conditions tolerable. But he also said that he repeatedly wished to die, especially after having to face two mock executions. Ebrahimi thought death would be painful for a second but that it would end his ceaseless torture and indefinite captivity.

All quarantine is meant to do is to cut the coronavirus transmission chain. It is in the public interest and will eventually end. In quarantine, people can spend their time with various diversions at their disposal.

"Quarantine is a good opportunity for people to spend more time with their families; or if they live alone, to put more time aside for themselves," Ebrahimi said. “Human being can quarantine themselves and study to enhance their knowledge. Movies, books, cooking, and gardening are available. The only requirement is to not be in touch with anyone.”

Ebrahimi spent his solitary confinement in thought – when he was not being tortured. He thought about himself, his life and his past, but he did not have the tools to do what he loved, such as cooking, so in his mind he acquired ingredients and mixed them to make new dishes. Ebrahimi also likes photography so in his imagination he travelled the world, thought of where he had been, where he would go in the future, painted pictures of natural landscapes that he had never seen. And he took pictures of what he saw with his mind’s eye.

Some people who have experienced solitary confinement speak of how it feels to be later transferred to a communal ward or even released from prison. Many find that nightmares stay with them after they are freed – many have difficulty sleeping or being in confined spaces or are afraid of the dark.

Mazyar Ebrahimi is no exception. He says he still cannot tolerate closed spaces and cannot stay inside a car for long. Nightmares disturb his sleep. “The feeling is still with me, from my time in solitary confinement; if I cannot go out, I pace wherever I am, turning round and round as I walk.”

But perhaps his experience – which stays with him, and many others – can make it easier to endure a situation like quarantine.

”It’s like lifting weights, once somebody lifts a weight of a hundred kilograms, then moving weights like 20 kilos, 10 kilos, five kilos, will not be hard. He can lift the weight, although lifting the hundred-kilo weight may hurt his muscles and his joints and cause injuries. When you compare prison to other things, you see there is nothing to worry about. But it can also be a trigger that reminds you of frustrations and of a difficult situation.”

Mazyar Ebrahimi, who experienced prison, solitary confinement and torture, and is now learning to navigate a new society with all the challenges of being an asylum seeker, says that the new quarantine measures must be seen as a good thing for humanity. People must embrace it and use it, not only to protect themselves, but to protect others.

People in solitary confinement become desperate to see the light of the sun and to think of freedom. But in quarantine, one can open a window every day, and hope to pass through this unprecedented time having shared an experience with people all over the world.

Read other articles in the series:

Tales of Isolation, Creativity and Survival

Dissident Writer: I Survived Hell on Earth in Cuban Prisons

Turkish Writer: I Dreamed Up Novels in High Security Prison

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments