Health workers are the front line in our defense against the coronavirus pandemic – including hundreds of Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. But they are not in Iran; instead, they live in countries around the world, treating their patients, where they are admired and praised by the people and governments of the countries where they live. The one country where they cannot do their work is Iran.

Many of these doctors and nurses – who studied and served in Iran – lost their jobs after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. They were expelled from the universities and their public sector jobs, barred from practicing medicine, jailed and tortured, and a considerable number of them perished on the gallows or in front of firing squads.

The crime of these Baha’i doctors, nurses and other health workers was their faith in a religion that the rulers of the Islamic Republic believe is a “deviant” faith.

In a new series of articles, called “For the Love of Their Country,” IranWire tells the stories of some of these Iranian Baha’i doctors and nurses. In this installment you will read the story of Qamar al-Muluk Seif, a Baha'i convert from Islam, and a pioneer in laboratory science and medical diagnoses.

If you know a Baha’i health worker and have a first-hand story of his or her life, let IranWire know.

-

A baby girl was born to the Seif family in Tehran on May 5, 1916. The Seifs were a prosperous and devout Muslim family. The paternal grandfather of this newborn child, Sheikh Seif al-Din Mirza Qajar, was a scholar at the Qajar court and the cousin of Naser al-Din Shah. Qamar al-Muluk was four when her mother, Nosrat al-Muluk, passed away. She lost her father, Zia al-Din Mirza, when she was a teenager.

Adolescence and education

Qamar al-Muluk was sent to the Jeanne d'Arc high school in Tehran. The school had been established by French religious missionaries to Iran and was famous among schools for girls in the city. Today it has become a tourist attraction.

Qamar al-Muluk wishes to continue her education after high school but, at that time, women were only allowed to study at either the Dar al-Moallem (House of Teachers) or the Advanced School of Midwifery. Qamar al-Muluk enrolled in midwifery.

After earning her bachelor's degree, Qamar al-Muluk completed a specialized course in laboratory science at the Pasteur Institute.The field of laboratory sciences was not yet fully formed in Iran – but due to the widespread prevalence of infectious diseases, and at the request of the Ministry of Health, the Pasteur Institute held specialized courses in laboratory sciences for volunteers with paramedical degrees.

In 1936, the Ministry of Health, which was then run under the supervision of the Ministry of Interior, hired six women with laboratory expertise to work in Tehran’s newly established Central Laboratory. One of these women was Qamar al-Muluk Seif. Only women were employed in the laboratory, and medical students, who at the time were all men, were not allowed to enter. Qamar al-Muluk was appointed director of the laboratory.

Marrying Dr. Masih Farhangi

“It was 1937,” Qamar al-Muluk wrote. “One day, Dr. Mashouf, the head of the laboratory, came to my office. He was accompanied by an elegant olive-skinned young man who was later introduced to me as Dr. Masih Farhangi. Dr. Mashouf told me, 'Ms. Seif, this gentleman has come to learn laboratory work. Guide him. He will come here for a few days.' I wondered why he, a medical student, was allowed to come to the lab. I found out later that he had gone to the Ministry of Culture to arrange this. From the next day, when we had anything to analyze, he also worked with me through the necessary steps. He was a very polite and kind young man...”

This cooperation and acquaintance led to Qamar al-Muluk's marriage to Dr. Farhangi. Dr. Farhangi was a follower of the Baha’i faith, and Qamar al-Muluk was known as the granddaughter of a high-ranking Shia cleric to the court.

The two were married on May 5, 1938, after performing the Islamic and Baha'i marriage ceremonies. Their marriage lasted until the execution of Masih Farhangi for his belief in the Baha'i faith in 1981. Qamar al-Muluk always remembered “Doctor Jaan” (Dear Doctor, her nickname for Dr. Farhangi) and, wherever she was, she would praise him and his services to the Iranian people.

The newlyweds rented a house in Tehran. The upper floor was their home and the lower floor served as their private offices. Qamar al-Muluk installed a small laboratory in her office to more accurately conduct tests and diagnose diseases.

Despite having a thriving medical practice, the couple decided to leave Tehran in 1940 and to resettle in a provincial town that needed of a doctor.

Typhus had spread throughout Gilan province and severe outbreaks were occurring in the city of Rashet. The couple, who now also had a baby, chose Rasht for their new home.

Becoming a Baha'i

Dr. Farhangi never spoke with Qamar al-Muluk about the Baha’i faith. The two lived in peace without interfering with each other’s beliefs. But Qamar al-Muluk was an avid reader so she read her husband’s Baha’i books. Weekly socializing with Baha’i friends, observing her husband’s character and behavior at home and at work made her interested in the Baha’i teachings. Qamar al-Muluk converted to the Baha’i faith after the second year of their marriage, in Tehran, and later in Rasht she formally joined the Baha’i community.

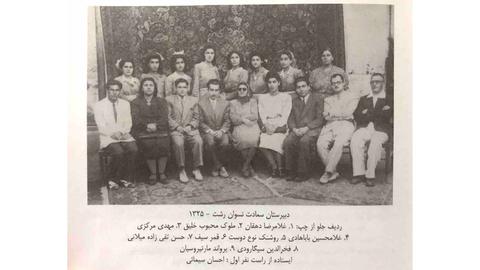

In Rasht both Qamar al-Mulk and Dr. Farhangi were employed at Poursina Hospital. Qamar al-Muluk is recorded as the first woman to establish a medical diagnostic laboratory in Gilan province.

“In all of Gilan province, from Ramsar to Hashtpar to Lowshan, there was only one hospital laboratory. Even the barracks medical office did not have a laboratory. Everything was sent to Poursina Hospital’s laboratory for analysis and we had our hands full. ... It wasn’t as easy in those days. We couldn't just buy the culture medium. We had to make boyun and gel from beef. We had to cook it and that was a big deal.”

World War II

By 1941, World War II had spread to the Middle East and Iran. Qamar al-Muluk and her family decided to emigrate to Iraq. They sold most of their household items (at low prices) and left for Iraq in June 1942. The family had grown to four – including a six-month-old baby. The extreme heat, the war, lack of medicine and powdered milk, and the illness of one of the children, caused great hardship for the family. But the family was determined to stay in Iraq and to help the deprived people of the country. The family settled in the city of Kirkuk.

When the people of Kirkuk, who were from Turkmen, Kurdish and Arab tribes, heard that an Iranian doctor had come to their city, they flocked to Dr. Farhangi's private clinic. The couple gradually became famous in Kirkuk and attracted even more patients. Even the head of the Residency Office and his family became their patients.

But the family had a problem because they did not have official permission to practice medicine in Iraq. Pharmacies would not give medicine to their patients. Qamar al-Muluk and Dr. Farhangi bought medicines from bankrupt pharmacies and gave them to their patients. They also made capsules and syrups by buying medical powders and using pharmaceutical formulas.

Expulsion from Iraq

Muslim clerics back in Iran had, meanwhile, been pressuring their counterparts and the authorities in Iran to expel the Baha’i couple from Iraq. The Iraqi authorities eventually bowed to this pressure and the couple was forced to return to Rasht.

The head of the health centers in Rasht sent a message to Qamar al-Muluk saying that her post at the hospital was still vacant. Qamar al-Muluk resumed her position as the director of Poursina Hospital’s laboratory and returned to work.

The return of the Farhangi family to Rasht coincided with the outbreak of a relapsing fever in Iran. Cases of the disease were common in Gilan. After the laboratory at Poursina Hospital was reopened it became the main center for diagnosing the disease in Rasht.

The family lived in Rasht for about ten years, during which Qamar al-Muluk's medical services made her a well-known and trusted figure among the women of the city. She was also an active and prominent member of the Baha’i community and served on the community’s Local Spiritual Assembly for Rasht.

Living in Turkey

Qamar al-Muluk and her husband now decided to move to Turkey. They wanted to help the small Baha'i community in Turkey while studying at Istanbul University.

They sold everything and raised funds to cover their expenses in Turkey. While attending school, they also volunteered to work at the university's hospital, to obtain residency. They returned to Iran six and a half years later, in December 1960.

Qamar al-Muluk later wrote in her memoirs that one of the most important tasks she undertook in Turkey was to gather together Iranian students with families back in Iran. Qamar al-Muluk and her husband treated these young people as their own and welcomed them into their home; if they were unwell, they treated them, and the young people would consult Qamar al-Mulk and Dr. Farhangi as though they were their own parents.

Returning to Iran

Qamar al-Muluk was invited to work for the health department of Gilan province on her and the family’s return to Iran. Malaria was rampant in Gilan at the time. Qamar al-Mulk’s experience prompted the health department to retain her to diagnose and combat infectious and microbial diseases and to work on the malaria control project.

Qamar al-Muluk served in the capacity for several years. She was later appointed head of the malaria office – she was the first woman in Gilan to take up this position.

In the book Pioneers of Gilan Culture, written by Marvaji and published in 2009, Qamar al-Muluk Seif was named as one of the earliest and most influential female teachers in Gilan. In the early years of loving in Rasht, and despite her busy schedule, Qamar al-Muluk voluntarily and at no cost to the school taught hygiene and childcare courses to 11th-grade and 12th-grade high school girls. These classes continued until the family left Gilan.

Moving to the capital and the Islamic Revolution

Qamar al-Muluk and her husband left Gilan, in 1968, after years of offering medical services to the people of the province. They settled in a small apartment in Tehran and lived in the capital until the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The Revolution changed everything. On the evening of February 6, 1980, armed guards entered the apartment Qamar al-Muluk shared with her husband Masih Farhangi. After searching the house, they arrested Dr. Farhangi.

Qamar al-Muluk heard nothing about her husband’s condition for a month – later learning that he was being held in prison but that she could not visit him. But she was happy that “Doctor Jaan” could at least practice medicine in prison where he treated other prisoners and guards.

On the morning of July 24, 1981, the radio announced the execution of five people on charges of “spreading corruption on earth.” One of them was Dr. Farhangi.

Leaving Iran after the execution of her husband

Qamar al-Muluk left Tehran to visit her daughter after her husband’s memorial. During the visit she learned that her apartment in Tehran had been sealed by the authorities. Qamar called the Revolutionary Court and asked on what basis her home had been confiscated. She was told to visit the court so they could show her her new living space – she realized that the Revolutionary Guards intended to arrest her. She went to Turkey.

The Baha’i community of Canada informed the Canadian government of Qamar al-Muluk Seif’s situation, asking for support. The country’s immigration minister, in a telephone call with Dr. Farhang Farhangi, Qamar’s daughter, said that Canada accepted her mother as an immigrant; Qamar al-Muluk moved to Canada at the age of 69 and lived in Hamilton, Ontario.

Qamar al-Muluk Seif (Farhangi) passed away on May 16, 2007, at the age of 95. She was hopeful and energetic until the last moments of her life. And despite her own decreased mobility, in her old age, she remained engaged in charitable work.

Read other articles in this series:

The Baha'i Cardiologist Who Challenged the Heart of the Revolution

A Baha'i Doctor Forced to Choose "Islam or Execution"

The Doctor With the Unforgettable Smile

A Devoted Pediatrics Pioneer Working in Dangerous Times

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments