Robert Weinberg is a writer and radio and podcast producer whose features and exhibition reviews have appeared in the Telegraph, Apollo, The British Art Journal and numerous other publications. In this guest feature for IranWire, he examines the remarkable story of how an American woman amassed one of the world’s most valuable modern art collections in Tehran, at the request of Farah Pahlavi, on the eve of the Islamic Revolution – a story now told by the curator herself, Donna Stein, in a book due to be published next week.

Since the late 1970s, a concrete and stone building has stood alongside Laleh Park in the centre of Tehran, its brutalist architecture incorporating quarter-circle vents inspired by the brick wind-towers of ancient Persia.

Last month this landmark, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA), reopened after a 30-month refurbishment with exhibits of conceptual photography and contemporary Iranian artwork. What is not on display, however, is the majority of the most valuable modern art collection outside of Europe and North America. It has been stored away in vaults, largely unseen, ever since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

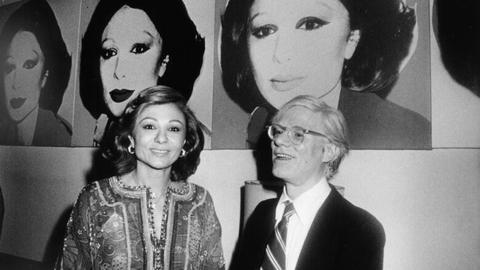

In the final years of Pahlavi rule, a young American art curator, Donna Stein, was given almost free rein at the request of Empress Farah to buy whatever works it would take to provide the people of Iran with a comprehensive survey of the history of modern art, from the French Impressionists onward. Stein scoured the world’s galleries and auction houses for paintings, prints, sculptures and photography, acquiring 350 pieces for less than $100 million. The list of her acquisitions is a roll-call of the giants of modernism: Renoir, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Picasso, Rothko, Pollock, Warhol and Giacometti, amongst others. Today this hidden collection is worth billions.

After four decades, Donna Stein has finally told her extraordinary story in a new book, The Empress and I: a “hybrid,” she calls it, “of autobiography, art history and political history”.

“I wrote the first outline in 1977,” she says. “But, you know, life intervenes. I had to work. I found jobs along the way that kept my attention, and I was content with doing what I was doing: curating and writing. And I had a child.”

But for years, Farah Pahlavi – now 82, and living between Paris and Washington D.C. – had been telling her former curator, “We need you to write this book. You have this information that no one else has.”

Finally, after retiring in 2016, Stein was able to gather together all the documents she had held onto for more than 40 years, and wrote down her memories of that time.

Stein describes herself a lifelong adventurer. It was this intrepid spirit that took her to Tehran on a research visit in 1973. That in turn led to a series of conversations, and finally to the extraordinary commission from the Shahbanu of Iran. Stein, who now lives outside Los Angeles, says the experience “absolutely changed me”.

The idea of establishing a museum of modern art in Tehran had initially been suggested by the surrealist painter Iran Darroudi. Farah Pahlavi then pushed the concept forward, appointing her cousin Kamran Diba to be the TMoCA’s architect and first director. The budget for the Museum and its collection came primarily from the National Iranian Oil Company.

Initially, Stein, who is an expert in printmaking, was tasked with building a collection of works on paper. She persuaded her Iranian colleagues to buy important 20th century photography as well. But when she went to Iran for her first interview, she was unimpressed by the art that had already been purchased, and her brief was duly extended.

“When I went back to New York for four months and started the work from there, I was told to look for paintings and sculptures,” she says. “So I started to investigate all media, and not just graphic arts. I was looking for quality and value, and for rare pieces.”

Having sourced a number of good works, Stein was surprised by her employees’ approach to bartering with galleries when they arrived in New York. “It was not easy! It was embarrassing to me in the manner that it was done. I would have been a fool to think that bargaining didn’t go along with the process of buying; we do that here, but not in quite the same way. I was just a little shocked by the method.”

After Stein moved to Iran, there were further challenges that tested her Western sensibilities. As an American feminist raised in the 1960s, Stein was left feeling isolated by the unconventional practices, complex bureaucracy and power play in the Empress’s office, with her loneliness exacerbated by the lack of English speakers and anyone with whom she could consult about her selections. Finally, when it was unclear whether her contract would be renewed, she confronted her line manager.

“I was very candid with him and spoke my mind,” she says, “and he appreciated that. He also found it difficult that I was so demanding. But it was for them, it wasn’t for me. I wasn’t gaining anything much, but I felt strongly that we should establish a quality collection, so I was very careful to research everything and give my true opinion. Over time, we established a good working relationship and I realized he was protecting me.”

Only two items from the collection failed to survive the early days of the revolution: Andy Warhol’s portrait of the Shahbanu – “Instead of cutting it up, they should have sold it,” Farah Pahlavi has since said – and a sculpture by Bahman Mohasses. “The fact that he was homosexual and proud of it was against the grain in terms of Islamic law,” reflects Stein. “I think that’s why he was picked on.” It comes as something of a surprise, then, that the new photographic exhibition at the refurbished Museum contains a work by Gilbert and George.

Another of the paintings Stein purchased was Woman III, by the abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning. The work was on loan to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. at the time of the Islamic Revolution and was seized by the US government. The piece was eventually returned to TMoCA, but in 1994 it was quietly deaccessioned and exchanged for a rare, illustrated manuscript of the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp by Ferdowsi.

At the time, Stein says, Farah Pahlavi was “thrilled” about the Shahnameh returning to Iran, “but she didn’t understand why they had to exchange it; they could have paid for it. She got so angry that she called the Museum and pretended she was just a regular Iranian, telling them: ‘Don’t ever sell any of those works. This is an extraordinary collection. Keep it together.’”

Stein had already completed her work and returned to the United States before the Islamic Revolution. She had not been particularly aware of the anti-monarchy turbulence that was beginning to stir in Iran during her stay. “I was not politically-oriented, so I wasn’t in the centre of all the politics of that time. I was the only foreigner in the Queen’s office. I don’t know if foreigners in other offices would have actually been aware of what was going on.”

But, looking back, Stein is in no doubt that the Empress was an important influence on Iran’s cultural life. “Her mandate was arts and culture, education and social welfare,” she says. “She was very active and she did an amazing job. Museums were established all over the country. She had a huge role in restoring old buildings and gardens, and she encouraged the development of the traditional crafts that Iranians are known for. The arts are her passion, and she did everything she could to advance that and to educate the people. It doesn’t seem to me that the revolution brought about something better.”

Despite the vast effort and sums of money that went into creating the collection, it has never been Farah Pahlavi’s desire for it to leave Iran. “She’s very happy that it’s there and wants it kept there,” says Stein. “She never had any ambition to try to bring it out, or in any way take it away from those she considers her people.”

Today, on display, there is the barest hint of the treasure-trove of masterpieces that are stashed away in the Museum’s basement. An Alexander Calder mobile, The Orange Fish, has continued to hang over the TMoCA’s atrium throughout the decades, and a sculpture garden boasts works by Magritte and Henry Moore.

Stein hopes that one day, she herself will be able to revisit those works, and the country and people that changed her life. “I remain haunted by my memories of the sights and smells of Iran,” she writes in her book, “as well as the immense kindness and occasional small-mindedness of its vivacious people. I would definitely go back if the circumstances were right.”

The Empress and I: How an Ancient Empire Collected, Rejected, and Rediscovered Modern Art by Donna Stein is published by Skira on March 30.

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments