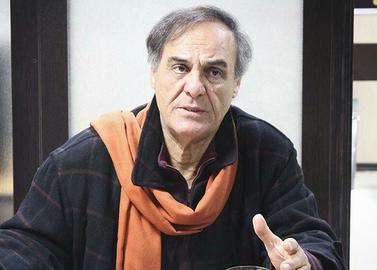

In real terms Ali Motahari, a former deputy speaker of the Iranian parliament, holds views on women’s rights and compulsory hijab that are not dissimilar to those of other officials of the Islamic Republic. But in his case, every time he repeats them, his words do not fail to astound.

In a recent tirade on the social networking app Clubhouse, the presidential hopeful compared women’s rights to animal rights. He went on to set a new low in terms of racism and sexism even by his own, well-documented standards.

***

Last year the Guardian Council disqualified Ali Motahari as a candidate in the latest round of parliamentary elections. Not undeterred, he has since announced his plans to run in the June 2021 presidential election.

On the evening of Tuesday, April 6, Motahari logged on to the video chat app Clubhouse to take questions from an audience of more than 6,000 people. Alongside other topics, he addressed the issue of compulsory veiling in Iran in even more misogynistic, blinkered and racist terms than usual.

Calling “freedom of dress” for women an “animal right” rather than a human right, he declared: “If somebody is not aroused on the beach, then he is sick. God wants us to get aroused. Men must be aroused. It is good that a young man is aroused by seeing the hand of a woman.”

Following this pronouncement, Motahari went on to say something we can only apologize profusely for having to cite here. “Right now,” he said, “they have problems in Europe. Men are not aroused and women are resorting to African men.”

A Consistent Misogynistic Line

These remarks by Motahari about enforced veiling, and his views on women in general, are in no way new and in fact have an exasperatingly long history. No matter what the occasion or who his audience is, this ex-MP has never shied away from expressing his convictions on the subject.

In a speech to the Iranian parliament in 2002, Motahari harshly criticized the “spread of bad hijab” in Iran. He accused then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Vice President Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei of having “cleverly” undermined Islamic dress code by making “pants and knee-length manteaux” the new standard for women.

This way of dressing, he said, was equivalent to “sexual incitement” and Ahmadinejad and Mashaei must now be thinking about “their next step: setting up cabarets and night clubs.”

Tehran prosecutor Abas Jafari Dowlatabadi initially said he was going to indict Motahari over the comments, as he had effectively accused the incumbent president and vice president of “not believing in hijab.” But he took no action in the end and no more was said about it.

In 2014, Motahari summoned the then-interior minister to parliament to explain why women in Iran were being allowed to wear leggings. At his request, pictures of women wearing leggings were shown on monitors in the chamber, which caused a stir among the representatives present. “Apparently these pictures have excited our friends,” Motahari said.

In a speech at a conference on January 7, 2019, while serving as deputy speaker of parliament, Motahari said that were a referendum on compulsory hijab held in Iran, “Even some of those with improper hijab would vote for it.” These words fell at a time when popular opposition to Iran’s draconian veiling law was gaining traction, and the “Women of Revolution Street” had recently taken to the streets and removed their hijabs in protest.

By the summer of 2019, numerous videos had surfaced on social media of unveiled women in the streets of Tehran and other cities. Motahari tried to dismiss them by saying that “only 10 or 11 such cases” had been identified across the country. But nonetheless, he called on the Interior Ministry to identify and “quickly” punish these women. New surveillance cameras, he suggested, could be installed for this purpose if necessary.

On October 5, 2019, during a Q&A session at Tehran’s Beheshti University, a female student asked Motahari not to take “amnesia pills” and forget about political developments in the country. He responded: “I am taking my pills, and I have some birth control pills for you.” When an outcry ensued, Motahari said his comments had been meant as “a joke” and falsely claimed that the questioner had been a man.

Earlier that year in a TV interview, Motahari had also bizarrely claimed that there was no such thing as “compulsory hijab” in Iran, and that mandatory veiling was not “enforced harshly”. This caused a similar uproar on social media, including one response from a caricaturist.

Back in 2017, the male coach of the Thai women's national kabaddi team had been made to wear a headscarf in the stadium of the Iranian city of Horgan so as to evade a ban on men attending women's sporting events. “Couldn’t you have told me this before, so that I might not have become the laughingstock of everybody?” the coach was depicted as asking Motahari in the cartoon.

Perhaps the most incisive view into Motahari’s opinions on women came from an interview he gave this year, on January 7, 2021. In this interview, he defended his stance on compulsory hijab in great detail but, at the same time, he claimed yet again that it was not compulsory at all. At no point in this protracted discussion did he concede that these points contradicted each other.

More Extremist or More Blunt?

Some observers believe that Motahari is not a true representative of the Iranian regime on the question of hijab, because his views on the subject have been criticized by supporters of the regime as well as by its opponents.

It is certainly true that Motahari’s critics come from across the political spectrum. Three years ago, for instance, a prominent ayatollah in Qom wrote Motahari a letter reminding him that his views on hijab were not compatible with those of his father Morteza Motahari: an influential ideologue of the Islamic Republic who was assassinated in 1979, shortly after the Islamic Revolution. Another open letter criticizing him for his stance on hijab came from Sadegh Zibakalam, a well-known university professor.

Nevertheless, Motahari’s views on compulsory hijab are demonstrably in line with those of other officials of the Islamic Republic. What they want from him is not to be so outspoken about it. During the same Clubhouse chat on April 6, Mohammad Ali Abtahi, a former vice president under President Mohammad Khatami, put it bluntly. “What you are saying,” he told Motahari, “is good for not becoming president.”

The Note in His Father’s Pocket

Morteza Motahari had been a favorite pupil of Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic. He was well-known for his traditional and hyper-conservative views, even though in recent years the Islamic Republic has tried to paint him as a progressive. Despite this, there are some who say his son Ali is even more socially conservative than his father.

Motahari’s critics point to articles written by Morteza Motahari in the 1970s, before the revolution, for a magazine called Today’s Woman, which were later republished in a book entitled Women’s Rights in Islam. They also point to the contents of a note that was found in Morteza Motahari’s pocket after he was assassinated.

For his part, Ali Motahari has insisted that his views fully match those of his father. According to him, the notes found in his father’s pocket were a list of topics he had planned to discuss with Khomeini, including one that said: “Delaying the question of hijab until the establishment of Islamic order.” In other words, postpone the question of hijab until the new Islamic regime is firmly in control. Seen this way, the views of the father and the son do not appear at odds.

Related Coverage:

Khamenei: Women in Animations Must Wear Hijab

Khamenei Dismisses Hijab Protesters as “Insignificant and Small”

People Want the Choice on Hijab — But the Regime Won't Listen

From Rejection to the Death Sentence: The Fate of Iranian Clerics who Oppose Forced Veiling

Official Report: Support for Compulsory Hijab Plummets

Decoding Iranian Politics: The Struggle Over Compulsory Hijab

Iran’s Prosecutor Dismisses Hijab Protesters as Childish and Ignorant

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments