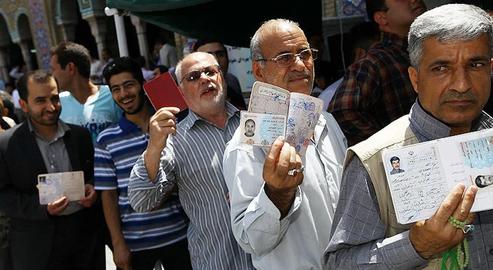

The 13th presidential election in the Islamic Republic of Iran is set to take place in a little under a month and a half. With half an eye on the current conditions, this report examines what impact – if any – the outcome of the vote might now have on Iran’s ailing economy.

Around this time eight years ago, a cleric named Hassan Rouhani registered as a presidential candidate. At that time, when Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani was also thinking of running, no one took Rouhani seriously. But Rouhani had launched his campaign before Hashemi Rafsanjani was disqualified on May 21, 2013, and ended up outlasting him, riding a wave of popular discontent and widespread desire for peace, clarity and economic improvement in Iran.

In the two years that led up to the 2013 elections, Iranian society had been in a state of socio-economic crisis: the worst since the immediate aftermath of the Iran-Iraq war. The then-Iranian government had reached a complete impasse in its domestic, foreign and economic policy. Rouhani was supposed to break this deadlock and save society from that unhealthy situation.

On the day Hassan Rouhani registered, he declared: "I have come with all my strength, background, and reputation to offer the people truth and integrity, with a government of wisdom and hope; with a manifesto of saving the economy, reviving morality and constructive interaction with the world, and taking steps to organize the people's affairs. I want their lives to get better."

The product of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's eight-year presidency had been a chaotic state of affairs in Iran. The product of Ahmadinejad’s “recklessness”, Rouhani said, had been inflation, disillusionment, and sanctions.

Eight years have passed since then. The dimensions of the political, economic and social crisis in Iran are now far broader than in 2013, with the damage wrought in the last three years far outstripping that of the disaster that befell Iran in 2011 and 2012. The question is, could a new premier salvage the situation in the same manner as Rouhani set out to in 2013?

Diagnosing the Data

To address this question, it may be helpful to refer to three main macroeconomic indicators: Inflation, economic growth, and employment. On all three scores, official data indicates that in contemporary history, the state of Iran's economy has never been worse than it is today.

The Iranian Central Bank has not yet announced the inflation statistics for 2020-2021 and may still not announce it for weeks or months to come. But we do know that for three consecutive years now inflation has been above 30 percent. Just under a decade ago, and before Rouhani’s presidency, the then-inflation rate of 22 to 30 percent in 2011 and 2012 was assumed to be the upper limit that Iranians could tolerate.

The Rouhani administration seized the opportunity to control Ahmadinejad's legacy of financial turmoil. Curbing the disastrous Mehr Housing Project, a flagship scheme of Ahmadinejad’s marred by waste and mismanagement, was enough to reduce inflation overnight.

Other small interventions like this meant inflation in the first term of Rouhani’s presidency was brought down to as low as 10 percent, and then held there – the lowest level it had been at since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

But the situation did not last. Iran's economic crisis began early in 2018, brought on in large part by the US withdrawing from the JCPOA. Now, any reference to Rouhani's government is intertwined with record levels of inflation and budget deficits which could take decades, not just years, to reverse. There are no projects left to put on ice: a large proportion of the budget is earmarked for a bankrupt government to pay the pensions and salaries of its employees.

The economic growth statistics for 2020-2021 have also not been announced yet, but official statistics make it plan that over the past 10 years Iran's sum economic growth has been zero. In the same period, the population has grown by more than 10 million and the per capita GDP of each Iranian has accordingly shrunk by about one fifth. Even in the 1980s, during and after aftermath of the Iran-Iraq war, this did not happen.

Iran's economic slowdown had begun before Rouhani took office. His team's prescription was to get out of recession by bringing about an end to sanctions and resuming oil exports. This was temporarily achieved, but after 2018, Iran’s economy foundered again – worse than before. The country has since experienced the longest and deepest period of economic recession ever recorded. So serious is the problem now that were sanctions lifted tomorrow, things would not improve in the short to medium term.

One of the other black spots on the record of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's government was that over the course of eight years, net employment growth was practically zero. Statistics show that between 2005 and 2012, only 9,000 jobs were created in Iran.

From 2013 to 2017, the Rouhani administration set about reversing this trend, creating an impressive two million jobs in four years. Unfortunately this trend, too, did not last, and official statistics have since shown that between 2017 and 2020, a cumulative total of 850,000 people left the labor market and more than 115,000 jobs were lost.

The economic downturn and then the pandemic reversed the fortunes of both the Rouhani administration and tens of millions of ordinary Iranians. In 2020-21 alone about one and a half million people left the labor market and more than one million jobs disappeared. Restoring the job market even to its pre-2018 state will now not be an easy task.

The rise and fall of the Rouhani administration in terms of economic management begs the wider question: what meaningful role can the executive branch play in ensuring economic prosperity in Iran not merely in the short term, but in the long term?

If anything can be learned from this eight-year period, it is that regardless of intent, the government has relatively little control over the long trajectory of Iran’s economy. Like other states, this is determined by a web of external factors – but also in Iran’s case, by the amount of power the unelected state cedes to the government to make radical – and not just surface-level – change.

Related coverage:

Iranians Enter a New Century Poorer and Less Hopeful for the Future

Rouhani's Employment Legacy: 800,000 Leave the Iranian Labor Market

Low Pay and Mounting Pressures: The Saga of Iranian Workers

Oil, the Dollar and Inflation: How Far Can the Economic Crisis in Iran Go?

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments