Anyone who has heard about the gruesome murder of Iranian film director Babak Khorramdin has been shocked. His dismembered body was found in three separate garbage cans on Nafisi Street in western Tehran in the early hours of May 16, and Khorramdin’s father confessed to the murder, with his wife admitting to being an accomplice.

But in the days that have followd, more grim details have surfaced. During questioning, Akbar Khorramdin revealed that he had previously killed his daughter Arezoo and son-in-law too. Like Babak, they were drugged with sleeping pills and then stabbed to death. Just as with Babak, their bodies were mutilated and dumped. All three were murdered, the father said, because they were morally corrupt.

Any time a murder within a family hits the headlines, it shocks the nation. But this horrific triple murder of three people in rapid succession by their own parents has been particularly traumatic. Iranians were still reeling from the story of Alireza Fazeli-Monfared, a 20-year-old man from Ahvaz, who was murdered in the city on May 4 by his brother and two cousins because he was gay.

In June 2020, we also learned of the murder of Romina Ashrafi: a 14-year-old Iranian girl from Talesh who was killed by her father with a sickle. Ten years ago, three teenage girls were murdered by their father near Takhtgah in Kermanshah, in one of the most heartbreaking criminal cases in the modern history of Iran.

"These events are part of the invisible underground of our society,” Saeed Payvandi, sociologist and professor at the University of Lorraine in France, told IranWire: "The many problems of Iranian society pave the way for such phenomena.”

The sociologist acknowledges the impact that murders have on societies, whatever the country. But Iranian society is unique, and in turn it means that the behavior and psyche of Iran’s criminals is somewhat unique too.

"In the case of the Khorramdin family, the discourse of the killers stands out,” Payvandi says. He says the way they talk about their crime closely resembles the language used in state media and in public discourse. “Tthey use the same logic, reasoning and values, and their remarks conjure up the same world, that the mainstream media presents. The parents' statements about the moral issues they attribute to their children are examples of a society that experiences these harms from within.

"Compared to in other countries, the motives for child murder in Iran are entirely related to a traditional society, and the gap between the younger generation and the parents’ generation is obvious. They are unable to understand their children, are unable to engage in dialogue with them or accept their lifestyle."

Since Babak Khorramdin’s murder on May 16, there has been widespread speculation about his relationship with some of his female students, prompted by his parents’ accounts of him bringing women back to the family house. Prior to this, in an interview with IranWire, some of Khorramdin’s friends had also made allegations that he had raped and sexually assaulted several girls: accusations that had also appeared online. In addition, a friend of Arezoo Khorramdin claimed that her father had raped her. IranWire was unable to independently confirm these allegations.

How will Sharia Law be Applied?

If Akbar Khorramdin claims his victims were "corrupt" and that they were "mahdoor al-dam" [individuals who are not entitled to protection, and whose blood, under Sharia law, can be shed without punishment], could he be exempted from having to pay retribution costs or even serving a prison sentence?

If so, what verdict will be handed down? Musa Barzin Khalifehlou, an Iranian lawyer based in Turkey who regularly advises IranWire, and Tehran-based lawyer Mohammad Hossein Aghasi say if the judge can be persuaded the victims were corrupt as it is defined under Sharia law, freedom for the killers is possible.

Aghasi says the possibility of a death sentence is unlikely for the Khorramdins. According to Mohammad Oliaeifard, another lawyer who regularly advises IranWire, the only charge that would secure a jail sentence for the pair would be “corruption on earth”.

“If the judge finds that the pair have disrupted the psychological security of the community and its citizens and tried to harm the social system, then he could issue a death sentence, which we have witnessed in the past,” he said. “But so far, there has been no news about other people being murdered other than the family members. Since it’s family-related, the possibility of accusing the killers of corruption on earth is low."

It will be difficult for the judge to charge the murderers with "corruption on earth” since they claimed the victims were morally corrupt themselves, Aghasi argues.

“If Babak Khorramdin is mahdoor al-dam, there must be evidence to prove this,” says Aghasi. “As for Arezoo, the father's claim that she was complicit in the murder of her husband and was an addict and corrupt is not valid as the only evidence.”

Aghasi further explained that because of the relationship between the killer and two of his victims — his children — Akbar Khorramdin could be sentenced to between three and 10 years in prison for their murders. When it comes to the son-in-law, if his only parent, his mother, decides she wants Khorramdin to face a sentence of retribution, known as qisas in Sharia law, it is possible though not likely that he could face the death penalty.

"If the victim's mother, as the sole parent, who is also the killer's relative by marriage, withdraws her legal complaint, Akbar Khorramdin and his wife will be saved, and will pay a sum of money to their son-in-law's family,” Aghasi said.

So it is the son-in-law’s family alone that will be in a position to ensure a death sentence will be handed down.

But Barzin Khalifehlou, Aghasi and Oliaeifard all agree that the parents are unlikely to have to face a retribution sentence and are more likely to spend several years in prison: 10 at the most. Even if the son-in-law’s family disagree with the moral corruption claims made by the killers, a full retribution sentence is unlikely.

"Some have said the punishment for the mother will be greater than for the father, but this is not true,” says Barzin Khalifehlou. “Certainly the sentence for the mother for complicity in the killing will be weaker than the sentence for the main killer.”

"The law does not oblige the accused to provide clear evidence that the victim was mahdoor al-dam. As soon as the killer proves to the judge that he killed the victims because he genuinely believed they were unworthy and that he had no other motive in killing them, he will be acquitted of retribution and a prison sentence will be handed down.

“This leaves the door open for murderers to use the mahdoor al-dam excuse to escape long term jail sentences. Why should anyone be allowed to impose Islamic punishment on his own?”

Oliaeifard also says in cases like this, Iranian law is skewed in the favor of the killers. “Currently, the parents say that they are not upset about the killings, and the mother has made an implicit claim that she was harassed by Babak,” he notes. "The judge can acquit them outright, sentence them to 10 years in prison, or execute both. We'll have to wait and see what the defense will be."

Aghasi also says that the rape allegations will have little impact on the case. “It is not legally possible to rely on people [accusers'] claims alone,” he says.

Iran’s domestic laws are in urgent need of reform, Barzin Khalifehlou adds. “We are not yet aware of many of the hidden angles of this case. For example, maybe Babak knew about the murder of his sister and son-in-law and, through his silence, helped conceal this overthese years. Was the daughter really complicit in her husband's murder? The answers to these questions will have an impact on the verdict. If the forensic department confirms the parents have a mental disorder, this also could be another reason for a death sentence to be ruled out.”

A Long History of Serial Killers and Familicides in Iran

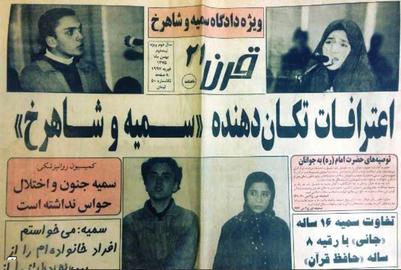

On Wednesday, January 1, 1997, a 16-year-old couple known as Somayeh and Shahrokh committed what came to be a notorious crime on Gandhi Street in Tehran. The murder, many details of which remain unsolved, has until a few short days ago, always been regarded as Iran’s most chilling murder case.

Ali Asghar Boroujerdi, known as "Asghar the Murderer,” was the first serial killer to be tried in Iran, on May 27, 1934. Boroujerdi raped and killed at least 33 young boys and teenagers, and he committed his crimes beyond Iran’s borders and into Iraq and other neighboring countries. Boroujerdi mutilated his victims’ corpses after killing them, storing them in kilns and qanats — tunnels used to transport water.

In the 1990s, Mohammad Basijeh, known as Bijeh, became one of the most famous and controversial serial killers in Iran’s history. Carrying out his crimes in the city of Rey and across the Pakdasht region, he raped and murdered 17 boys and five adults, setting their bodies alight in the desert after he killed them. He was eventually charged for the crimes and later executed.

In the 1980s, serial killer Majid Salek Mahmoudi confessed to raping and killing 21 women.

Gholamreza Khoshrou, known as the Night Bat, killed nine women after raping and mugging them; he was eventually sent to trial and executed.

Saeed Hanaei, known as the Spider Killer, killed 16 prostitutes in a single year.

The Kerman “circle” killings, carried out by six young Basij members in a mosque in Kerman in 2002. The group claimed that they had been inspired by spiritual leader Mohammad Taqi Mesbah’s guidance on how to deal with corruption, and set out to rid the city of corruption through targeting immoral individuals. Five deaths were attributed to them, but some media outlets claimed that the group had killed 18 people.

Farid Baghlani, known as the "cyclist killer,” killed seven women, eight girls and a boy.

Mahin Ghadiri, a murderer of elderly women, and Farzad, a serial killer of women in Gilan, are also among the most controversial cases.

Now the murder of Babak Khorramdin, his sister and his brother-in-law has come to light: an incident that will cast a long shadow over Iran in just the same way as these other horrific crimes have done.

So what impact will these and other killings have on Iranian society, and what harm will they do in the future? "Filicide like the tragic killing of Romin has never been discussed or evaluated in Iranian society so as to form a new kind of social consciousness," says sociologist Saeed Payvandi. "As a result, in Iranian society, everyone deals with this issue according to his or her own position. For example, some people, often those who have a traditional view, legitimize it and think it’s the parents’ right to choose how a child is treated. At the same time, a group that is critical and opposed to violence wil be shocked.

"The main problem of Iranian society in the face of such crimes is the lack of review and investigation of these catastrophes, especially by the influential national media, and those who ultimately have power over society. Elite, powerful cultural figures should engage in public debate over why such things happen, and how such crimes or the emergence of such criminals is dealt with in society. These people were not born criminals, but became criminals in the context of this situation.”

These cases are disturbing and shocking, but violence of a less dramatic, but equally damaging nature is far more common. The latest statistics on domestic violence in Iran, including psychological abuse, show a growth of 46 percent. In the last two years, domestic violence against children has increased fivefold and violence against women has tripled. Of all violent crimes in Iran, domestic violence is the most common, including so-called “honor” killings.

The exact official figures on honor killings and child homicides in Iran have not been made available. But according to the Iranian Students' News Agency, citing academic research alone, between 375 and 450 honor killings are known to occur annually; many of these killings are child murder.

Payvandi also highlights the role Iran’s flawed judicial system plays in facilitating such crimes. "The judiciary is complicit with these people. This means that Iran's judicial and criminal law dealing with family homicides is predicated on hierarchy and provides a legal framework in which parents can easily engage in such acts. In this regard, there is no opportunity for assessment or review of society so that our judicial law can learn from these situations."

In the Babak Khorramdin case, despite the parents’ confessions, there are still many missing links and not all the allegations have been independently verified. What is clear is that Iran has seen an increase in family homicides in recent years, and, in particular, an increase in child murder. At the same time, Iranian society has not yet found a way of how to deal with the issue. The Ministry of Health is in no position to adequately assess what impact it is having on the nation’s mental health, or what impact it will have on the future.

Related coverage:

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments