Robert Weinberg is a writer on art history and radio and podcast producer, whose features and exhibition reviews have appeared in the Telegraph, Apollo, The British Art Journal and numerous other publications. In this guest feature for IranWire, he reviews the Victoria and Albert Museum’s current blockbuster exhibition, Epic Iran.

One of the early objects on show at the V&A’s Epic Iran exhibition is a tiny figurine of a person riding a horse, man and beast merged together from a lump of clay by 2,500-years-old fingers: once a plaything, now a poignant funerary treasure found in the excavated grave of a child. Several rooms and as many hours later (if you stop to examine each of the hundreds of items on display) the show ends with Avish Khebrehzadeh’s hypnotic All the White Horses (2016), in which a herd of hand-drawn, animated white horses thunder through limitless space towards the exit.

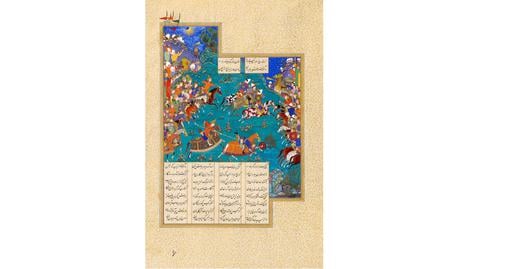

In the rooms between, equine imagery provides one of the recurring motifs that have transcended time and countless changes of rule over five millennia of Iran’s history. They figure prominently in Ferdowsi’s epic poem the Shahnameh, penned a relatively recent 1,000 years ago, which kept the heroism of Iran’s Sasanian empire alive, giving its subsequent rulers an unassailable past to emulate. Despite the changing religions, languages and regimes, these images that typify Iran’s national character provide the indissoluble thread that runs through the 5000 years under review.

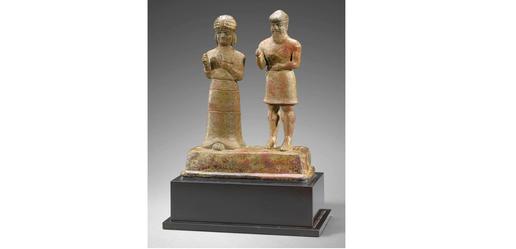

The blending of human and animal forms are first encountered with a male figurine (about 3200-2900 BC). At that time, people in urban centres such as Susa and Tepe Sialk were developing metalworking skills to rival those of Egypt and Mesopotamia. A silver antelope pendant, dazzling gold vessels and meticulously-crafted bronze figures denote the wealth of a series of small states that flourished in Western Iran from around 1200 BC onwards. Cyrus the Great’s adoption of Median art gave rise to pieces that to our eyes seem strikingly modernist. A pottery jug in the shape of a humpbacked bull from 1200-800 BC and its attendant figurine could have stepped straight out of a Picasso painting. A Piravend figurine, with its large head and stumpy body, would be equally at home in the retrospective of French modern master Jean Dubuffet (currently showing across town at the Barbican). But all of this says more about the possible exposure of twentieth century artists to works from ancient civilizations than it does about the originality and sophistication of what Iran was producing.

From the period of Darius the Great (522-486 BC), Persepolis remains one of the best preserved sites of the ancient world. In a show-stopping moment, this exhibition brings it to life as projections of vivid colours – the same that originally endowed realism upon its intricately-carved figures – are overlaid onto great slabs of the palace. Against this backdrop, the dramatically-lit lion- or horse-headed gold and silver drinking vessels, known as rhytons, must be among the world’s most breathtaking and dazzling treasures.

Iranian craftsmanship flourished all the more after the Safavid empire brought the country under Shia Islam in the 1500s. The V&A’s founders commissioned full-size replicas of some of Isfahan’s most dazzling domes and walls, which capture the apex of Iranian civilization. These form the second of the exhibition’s highpoints, overarching the sumptuous robes and intricate carpets, in which humanity’s relationship with the natural world has never been more skilfully interwoven.

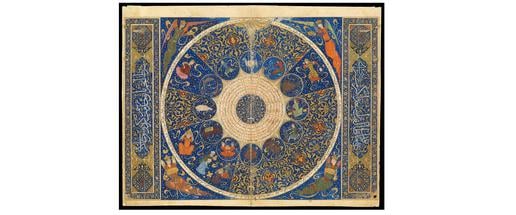

During this period, tales of the Twelve Imams moved from the margins of society to the center. In Imam Reza defeats the Red Demon (1550s), the Eighth Imam takes on a horned monster in a landscape as luxurious and populated by tormented souls as Heironymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. A century later, the Chagall-like Isfandiar Escapes the Simorgh’s Attacks (1648) – in a manuscript commissioned by the governor of Mashhad and now owned by HM The Queen – demonstrates the same high degree of pictorial skill, which combined text, storytelling imagery and a mastery of decorative detail. In so many of these illuminated manuscripts, the use of flattened perspective, the robed figures endowed with unique personalities, and the attention to natural detail, evoke similar imagery being produced in Renaissance Europe or Edo-period Japan, begging the question: What kind of cultural exchange was going on in this period, and who influenced whom? And if so, how?

Unlike Japan, however, Iran does not seem to have developed its culture in a vacuum. Influences were absorbed and given a unique twist. One of the exhibition’s most unexpected images is a 1676 painting by Muhammad Zaman, Sheikh San’an Encounters the Christian Maiden. It depicts the celebrated mystic meeting a Christian girl whose beauty causes him to abandon Islam for a while. Here, along with Armenian artists in Isfahan, Zaman painted in a resolutely European style, through which he created a popular aesthetic in the 1670s. Next to it hangs Venus and Cupid with a Satyr (1733), in which Muhammad Ali makes a coloured version of an engraving by the Netherlandish printmaker Raphael Sadeler. Its unabashed nudity and upskirting satyr would never see the light of day in contemporary Iran. But these images are also noteworthy in that, in the European manner, the name of the artist as unique personality begins to break through the anonymity of the artisan-craftsman.

In the nineteenth century, Iran’s kings recognised the potency of having themselves painted in the most complementary style, also showering their European counterparts with diplomatic gifts of portraits. Fath Ali Shah had many such images painted of himself and, in one room here, he presides over the display, ever young and virile with a lustrous black beard. Naser al-Din Shah Qajar’s travels to “Farangistan” turned him into an early adopter of photography and Western innovations.

It is towards the end of this chronological survey that one begins to see how Iranian artists – as with their European counterparts – only began to engage with personal expression relatively recently. In the twentieth century, international modernist movements began to expose Iranian artists to new ideas as they travelled or enrolled in academies. Nevertheless, the ancient motifs continues to linger.

Sacred iconography and profane everyday objects were juxtaposed and re-configured in the experimental works of the Saqa-khaneh school. In Meem (1958), for example, the anti-monarchist and Marxis, Siah Armajani combines references to the Archangel Gabriel, Sufi incantations and Noah’s Ark. Creation of the Planet (1963) by Marcos Grigorian is at once a spinning mass of straw, paint, dried mud and earth and a metaphysical meditation on the origins of the cosmos, as if – not unlike William Blake – he is seeing the world in a swirl of sand. Massoud Arabshahi’s Farvahar (1977) gives architectural dimensions to a symbol associated with Zoroastrianism, while Mohammad Ehsai’s Oo Bakhshandeh Ast (2003) stretches the boundaries of calligraphy, ordaining it with kinetic power.

Critical voices and women artists are inevitably few, although Shirin Neshat’s powerful video installation, Turbulent (1998), offers a haunting commentary on the post-Revolution ban on women singing solo in public. On one screen, a male singer intones a Rumi love poem, while across the room, a woman waits in darkness and silence, before replying with anguished ululations. Her wailing and the sound of galloping horses, punctuated by a gong, bring this exhilarating journey to an end with a question.

Where will those white horses, this ancient and dynamic culture, venture next?

Wherever they may go, it’s certain that five millennia of visual magic and exquisite craftsmanship will not be left behind. Epic Iran – whether you gallop or canter through it – is certainly worth the ride.

Epic Iran is at the Victoria & Albert Museum until September 12. https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/epic-iran

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments