“I’m here on behalf of my grandmother, who died wishing for this day to come. Her two sons were executed, and Siamak was her grandson. I’m here on behalf of my father, who died wishing for this day to come. I’m standing here asking for justice on behalf of my mother, and all the mothers, wives, sisters and children who clawed at the soil of Khavaran Cemetery.”

It’s Tuesday, August 10, 2021, and since the crack of dawn the pavement outside Stockholm District Court has been heaving with diverse political groups and reporters waiting for the first session of Hamid Nouri’s trial to begin.

For the first time in the history of the Islamic Republic, one of the officials involved in the 1998 massacre of thousands of political prisoners in Iran has been charged with a criminal offence – in this case, with war crimes and first-degree murder.

The opening of this historic trial in Sweden coincided with the inauguration of new President of Iran Ebrahim Raisi, who shares culpability for this unpunished crime against humanity. In 1988, Raisi sat on one of the “death panels” commissioned to send jailed Iranians to be systematically slaughtered, by people like Nouri, on the orders of Ayatollah Khomeini in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq war.

The victims were hanged from cranes and from ropes in the assembly halls, or shot by firing squad, before being buried en masse in unmarked graves. Even when the killings officially subsided in September, other survivors continued to “disappear”.

It’s Tuesday, August 10, 2021, and people are holding aloft pictures of some of the victims, and of the bereaved Iranian women known as the Khavaran Mothers. Those in attendance stare at the entrance to the large, imposing court as though expecting the truth to come flying out of the doors.

There’s music playing. Another group is chanting slogans. In one corner supporters of the People’s Mojahedin Organization (MEK), whose members were slaughtered in the “first wave” of killings that summer, have raised its banner aloft.

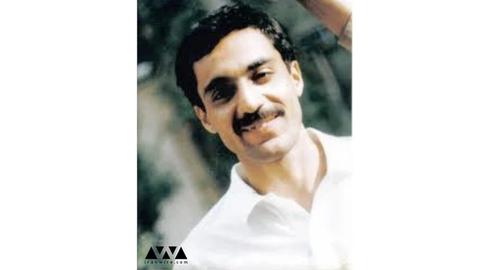

There’s limited space in the courtroom. When the trial gets under way the majority are left outside, holding each other’s hands, but also laughing and embracing. You can almost hear the heartbeats. And in the middle of this crowd stand two women, both of whom hold the same picture in their arms. It’s labelled Siamak Toubaei.

A Witness to the Massacre

The last time Nazila Toubaei saw her brother was September 5, 1981. Back then he was 18 years old and a student at Kharazmi High School. Like countless other students at the time, he handed out leaflets. His older sister believes it was his friends’ affiliation with the MEK that got him thrown in jail.

Now 61 years old, Nazila has travelled from the United States to be at Hamid Nouri’s trial together with her sister, Nina, from Canada. The pair are in search of answers about the fate of their brother, who spent years in Gohardasht and disappeared shortly after the massacre formally ended.

Recently, Nazila has been dreaming about that moment in 1981. “I had this feeling it was the last timd I’d see him. But it looked like he was worried about me. ‘Take care of yourself,’ he told me, as I was leaving home.”

Siamak was sentenced to three years in prison for his politics in Iran. Three weeks later on September 29, a newspaper mistakenly printed his name on a list of prisoners who had been executed. The heart-stopping news was quickly corrected; Siamak’s friends had made a mistake.

Still alive and well, Siamak was tried again in late 1982. This time he was sentenced to 12 years in jail, and became one of the first to be transferred from Ghezel Hesar Prison in Karaj, northwest of Tehran, to Gohardasht (Rajaei Shahr): Hamid Nouri’s domain.

Six long years passed. Siamak’s mother was able to visit her son in early June 1988, but then in July the phones were cut off. For weeks the families had no idea what was going on and received no word from their loved ones. In those few weeks in Gohardasht, hundreds of people were being slaughtered behind bars under Nouri’s command.

In the aftermath, the families of some of the murdered prisoners received a small bag of personal effects or a will; nothing more. Siamak was still alive. But when his mother next laid eyes on him he had turned into a frail, haggard young man, weeping uncontrollably. Whenever she enquired about one of his fellow prisoners, he would wave his hand in such a way as to make it clear they were gone. She tried to notify their families.

Even after the 1988 massacre came to an end, the persecution of MEK members and other opponents of the Islamic Republic continued. Either because of their still-steadfast beliefs, or because of what they had witnessed, the stage-managed disappearances of those who had survived the mass execution began.

The Disappearing Act

On October 28, 1989, without prior warning, Siamak Toubaei came home on a leave of absence from prison. He was accompanied by two guards. According to his other sister Nina, their mother said she would go to the grocery store for supplies – but the guards stopped her, saying Siamak himself had to go.

“Siamak was sent to shop all by himself,” Nina says. “They waited for two and a half hours. But he was gone. He never returned.”

On the same day, security agents arrested their parents. Siamak’s father was released after 24 hours, but his mother spent more than two weeks in detention. “They’d arranged it so it would look like Siamak had absconded,” Nina said. “We didn’t know it at the time, but we later learned a number of others had fallen into the same trap laid by the Intelligence Ministry.”

Ever since that day in 1989, the Toubaei family has been searching for the answer to a single question: “Where is Siamak?”. This last, wrenching pain came on top of the grief they were already experiencing: on December 27, 1981 and then on September 29, 1982, Siamak’s uncles Bahman Nayeri and Bijan Nayeri, had been executed in prison.

“I’d Like to See Him”

Almost exactly 30 years after Siamak vanished off the streets, at a quarter to eight in the morning on November 9, 2019, Nina Toubaei’s phone rang. At the other end of the receiver was Iraj Mesdaghi, a former political prisoner, writer and human rights activist who publicly identified Nouri as his torturer in Gohardasht some years ago.

“Iraj sounded agitated,” she recalls. “He told me: ‘Nina, in 10 minutes, one of the culprits of the 1988 massacre is going to be arrested in Europe.’ The first person whose name came to my mind was Naserian [the alias of Judge Mohammad Moghiseh, a former prosecutor at Gohardasht under whom Nouri served].

“Iraj wouldn’t name him. But he said that he had been an assistant of Naserian. It wasn’t until three or four days later that Hamid Nouri was named, and my imagination went into overdrive.

“I couldn’t believe it. If Hamid Nouri opened his mouth and told the truth, the secrets about my brother’s final weeks – and those of many others who fell into the Intelligence Ministry’s trap – could be revealed.”

Nina saw Siamak in prison for the last time on April 7, 1987. The occasion was Nowruz, Iranian new year. Through hand gestures, she told him she was leaving Iran. “He said ‘Go, go...I hope justice will prevail and the truth comes out.’”

Hamid Nouri was kept in custody for a year and nine months while evidence was gathered for the prosecution. Hearings will take place for three days a week until well into 2022. Besides the mountain of evidence, scores of plaintiffs stand ready to testify about the crimes they say were committed by Hamid Nouri, in the hope that a little more light might be shed on the darkness of 1980s Iran.

Did the sisters ever imagine that they would come face to face with Hamid Nouri? “I’m here today, and I’ll stay here,” Nazila says. “I want to meet him face to face. I look like my brother, and I’d like Nouri to see me next to his picture. Perhaps the shock will make him tell us what they did to Siamak.”

To be continued.

Related Coverage :

Hamid Nouri Trial Opens in Stockholm

'The Nation is a Plaintiff': Scores of Iranians to Testify in Case Against Hamid Nouri

Hamid Nouri to Face Trial for War Crimes in Sweden Over 1988 Massacre of Iranian Prisoners

Iranian Ex-Prisoners Recall 'Courier of Death' Hamid Nouri Ahead of Sweden Trial

Justice at Last? 1988 Massacre Suspect Arrested in Sweden

A Move For Justice Around the World

Raisi's Crimes Against Humanity Will Haunt his Presidency

visit the accountability section

In this section of Iran Wire, you can contact the officials and launch your campaign for various problems

comments